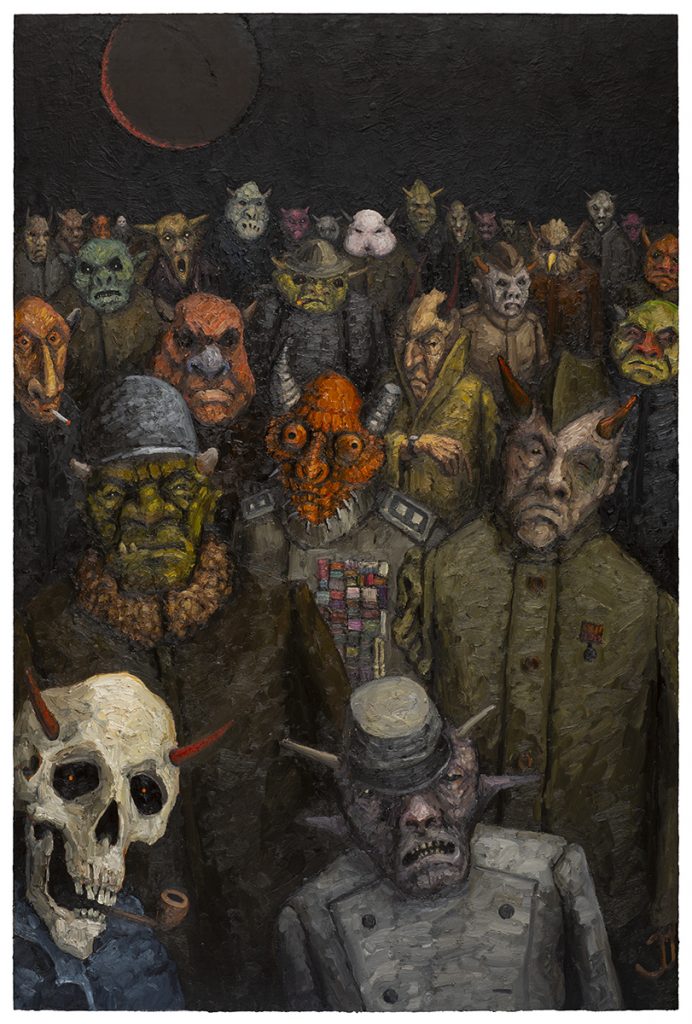

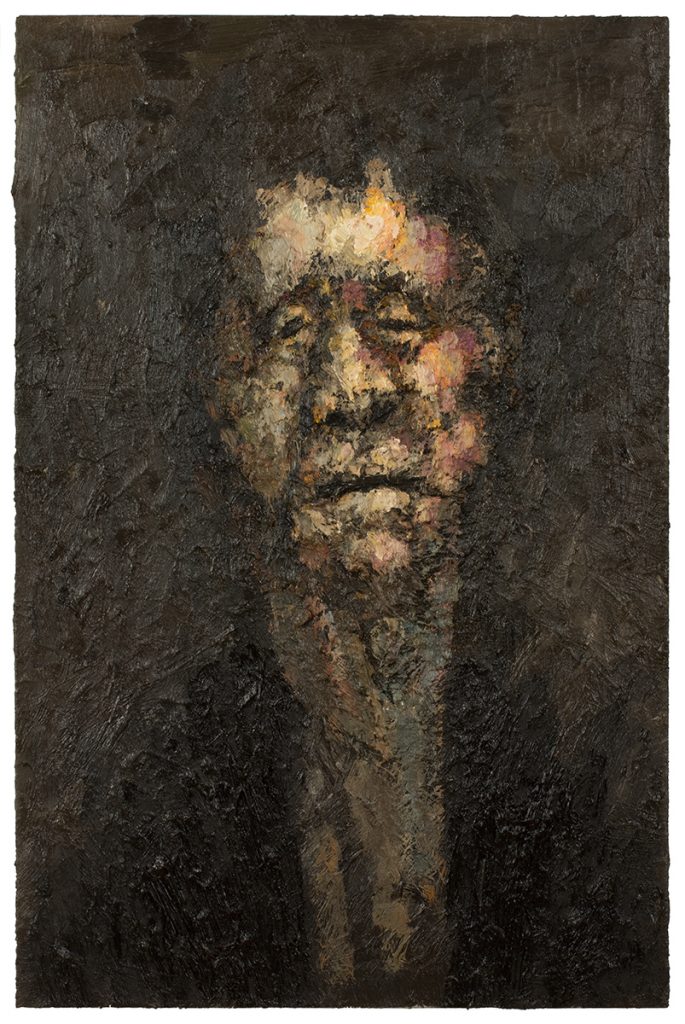

Though he has been painting and drawing them for years, James Deeb’s cast of ghoulish characters seem especially attuned to the present moment. Realized in thick impasto and often sickly color, they are bloated, demonic, smug, and menacing. They have obvious antecedents in artists like Goya and James Ensor. A tableau like Pyle’s Regiment (2018), with its cluster of fiendish misfits, is bound to recall Ensor’s biting masterpiece Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (not to mention the protagonists from any number of sci-fi and horror movies).

When an artist focuses on the profane and the ugly for decades, the writer is bound to wonder, What went wrong? Are there roots in childhood for this level of sardonicism?

For sure, Deeb did not have an easy start in life. He was born in West Berlin, inside the wall that still divided the city in 1964. His father was in the Air Force, and the family had already moved around a lot, living in California and Texas before Deeb was born. In Berlin, “they were still rebuilding after the war,” he recalls. “It was a very strange time, and my mom always described it to me as tense because of the wall.”

His father died of a heart attack at the age of 32, when Deeb was three. His parents were getting ready to go to Moscow for a new posting. Instead the artist and his mother and older sister moved to Mishiwaka, IN, where his mother had been raised. “It’s very much small-town Americana,” he says. “I don’t know how to describe it other than a sort of blankness. There was always a sense of melancholy. It took me a long time to understand the full impact of what it means to lose a parent at that age. Everyone I knew had the classic nuclear family, with 2.5 kids, a dog, and a cat. We were oddballs.”

Deeb turned to art, making drawings and animated movies with little clay models. “I was a huge fan of fantasy films,” he recalls. “I wouldn’t say we were indulged as children, but my mother always enabled us to do what we wanted to do. And so she bought me a movie camera and an editing machine.”

When he went off to college at Indiana University, his initial intention was to study mathematics, though he took art classes as electives. “I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was hooked,” he says. “Years later, when I was in graduate school, I had a mentor who made the comment that art is one of the few places where you can do research the moment you sit down. You’re always digging into your subjective experience, even with the most traditional kinds of training.

“I had this past I needed to excavate,” he adds. “That initial idea of being able to research immediately was very appealing.”

Nonetheless, after graduation, Deeb took four years off before applying to grad schools. “I’d been in school all my life, and I was getting very burned out. I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t know how.” It was clear, though, that if he wanted to teach, then as now one of the most viable ways for an artist to support himself, he would need that MFA. At Western Michigan University, he began working in the darker imagery that informs his calling today, but by the time he got the degree, he “realized the road to a tenure-track position was a lot longer and more fraught with problems than I thought it was going to be.” The academic life meant working as an adjunct or as replacement faculty, moving regularly to find work, and possibly a decade of upheaval. Given the dislocations of his early years, it seems no wonder that Deeb has chosen to support himself doing business graphics from his studio in Evanston, IL

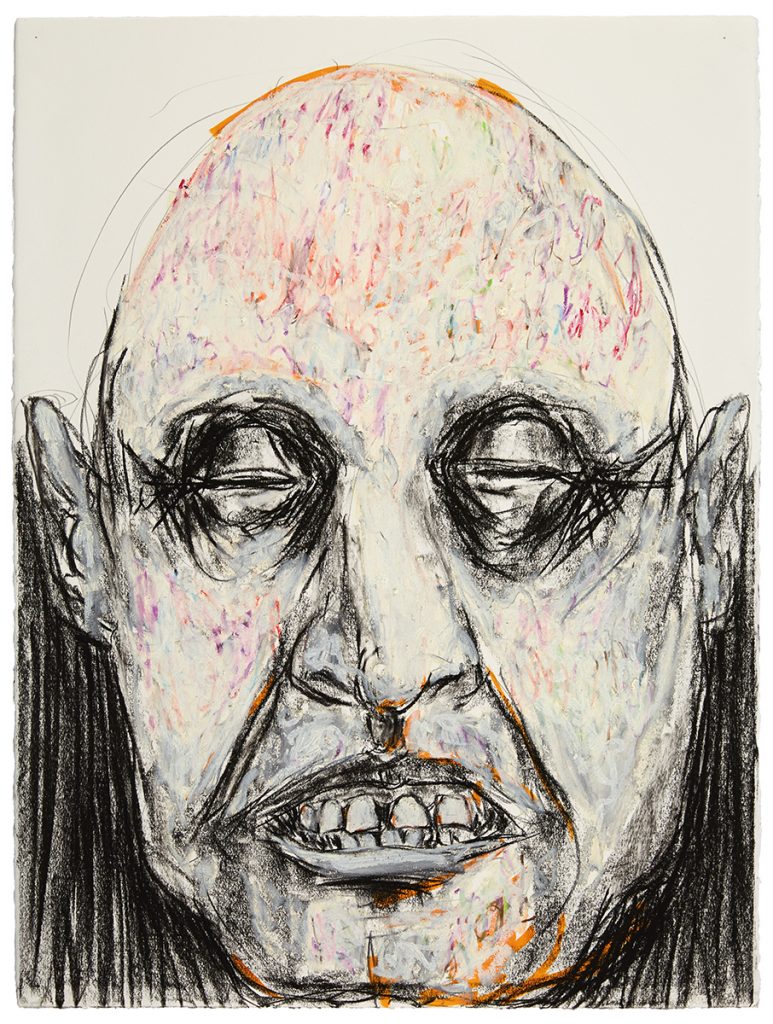

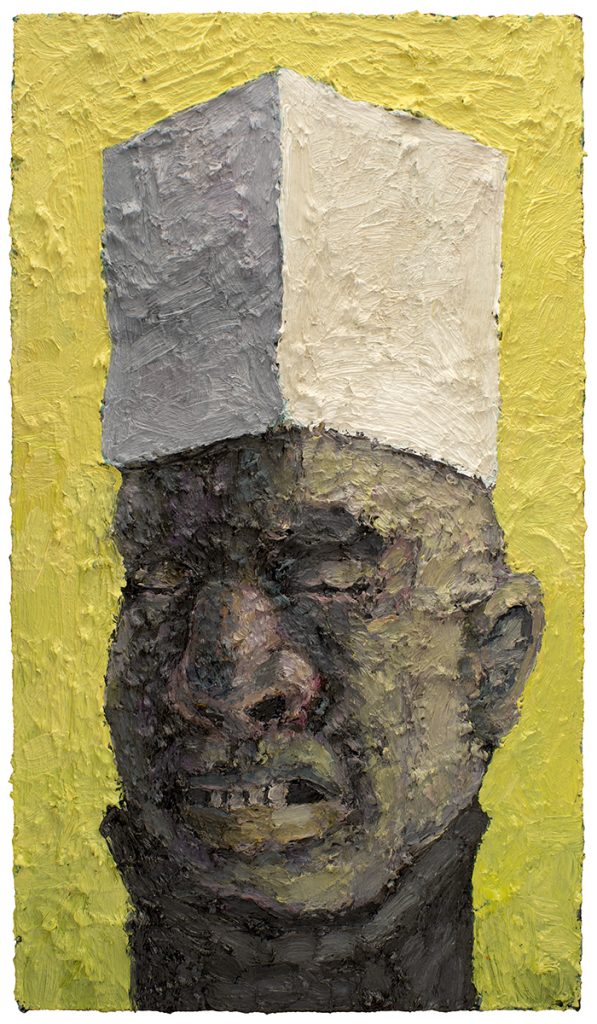

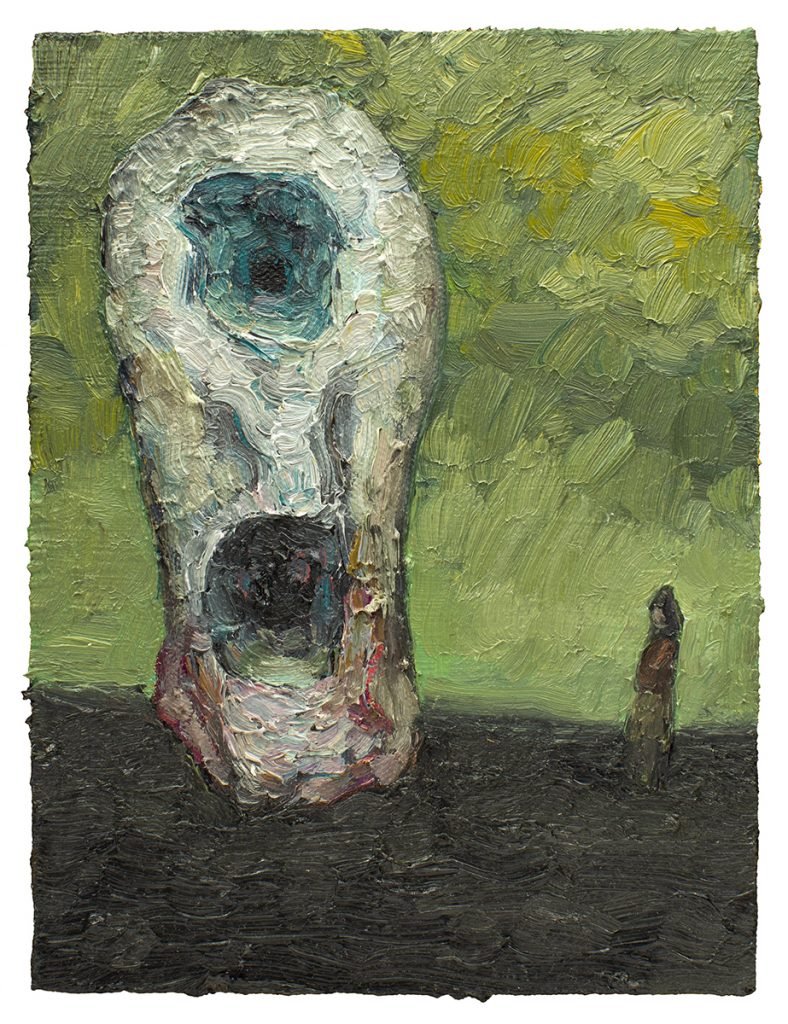

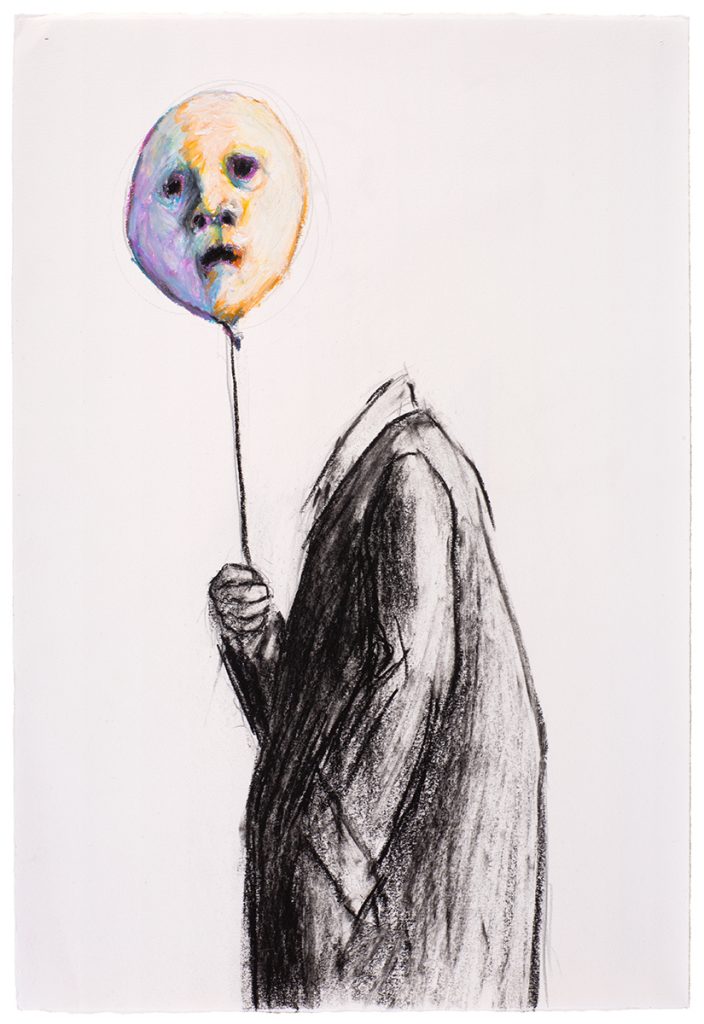

Deeb’s world does not comprise portraiture, nor is it caricature in the tradition of Daumier, Ralph Steadman, or any number of contemporary illustrators. But it’s inevitable, especially now, that some of his subjects will seem eerily familiar (“Hey, isn’t that Rudy Giuliani in that drawing?”) There are also elements of ghoulish fantasy in his repertoire, reminiscent of Odilon Redon and other late 19th-century Symbolists: in The Ghosts on the Shore (2018), a collection of disembodied balloon-like heads floats against a sunny yellow background. In Disquiet Monument (2019), a cyclopean apparition seems to scream at the bystander in the lower left.

Deeb admits that the dark humor that’s part and parcel of his paintings and drawings is very much a component of his outlook on life. “I’ve never thought of them as funny,” he says, “but I’ve lightened up a little. The type of line that I draw—and the type of line that goes into making caricatures or cartoons—is actually a lot of fun to draw. It might be a little self-indulgent, but it also expresses something about my personality, which I’m perfectly fine in allowing into the work.”

Many of Deeb’s characters, wearing regal garments or given the title of king, seem to hail from a dark and tragic place that could easily nourish a fallen hero like Lear or Macbeth. At the same time, many of his characters—such as Somnambulist (2017) and Umbra (2019)—seem possessed of a certain world-weary dignity.

When we encounter Deeb’s people, we realize that we know them, we have seen them on the news and in our nightmares. Maybe they are part of our entourage of family and friends. Maybe they even reflect aspects of our own darker natures.

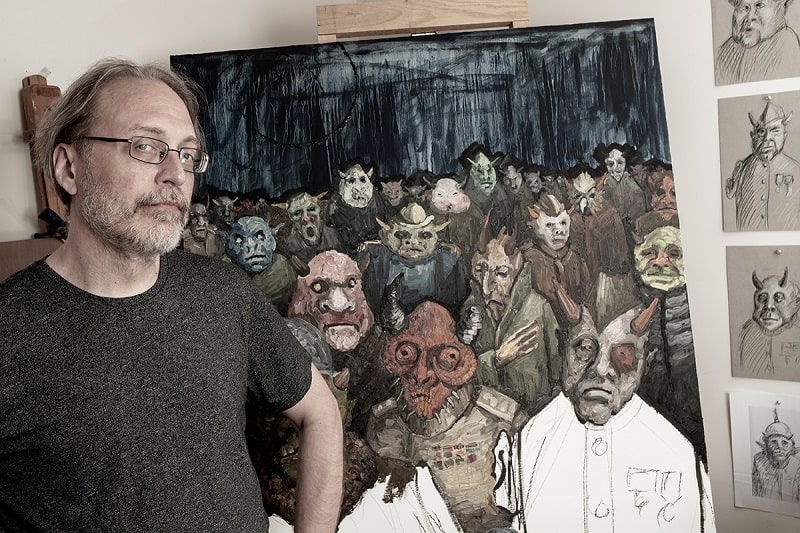

Top: James Deebe in his studio in Evanston, IL (photo by Joerg Metzner). More information about the artist can be found on his website.