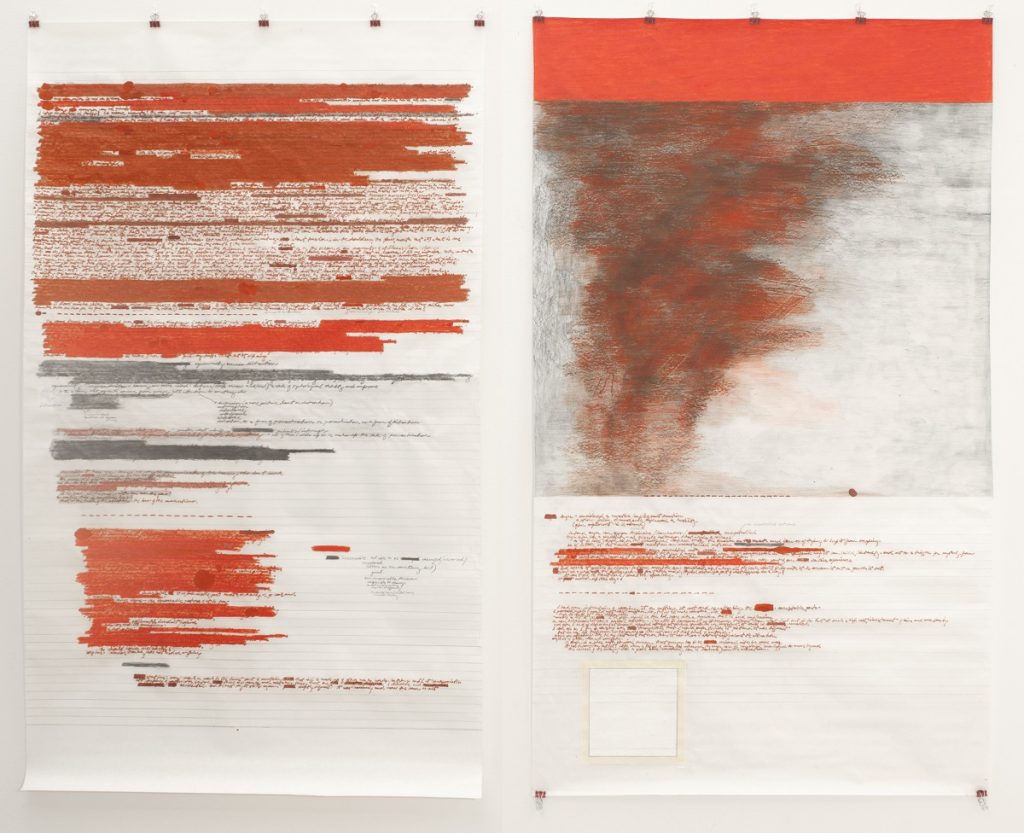

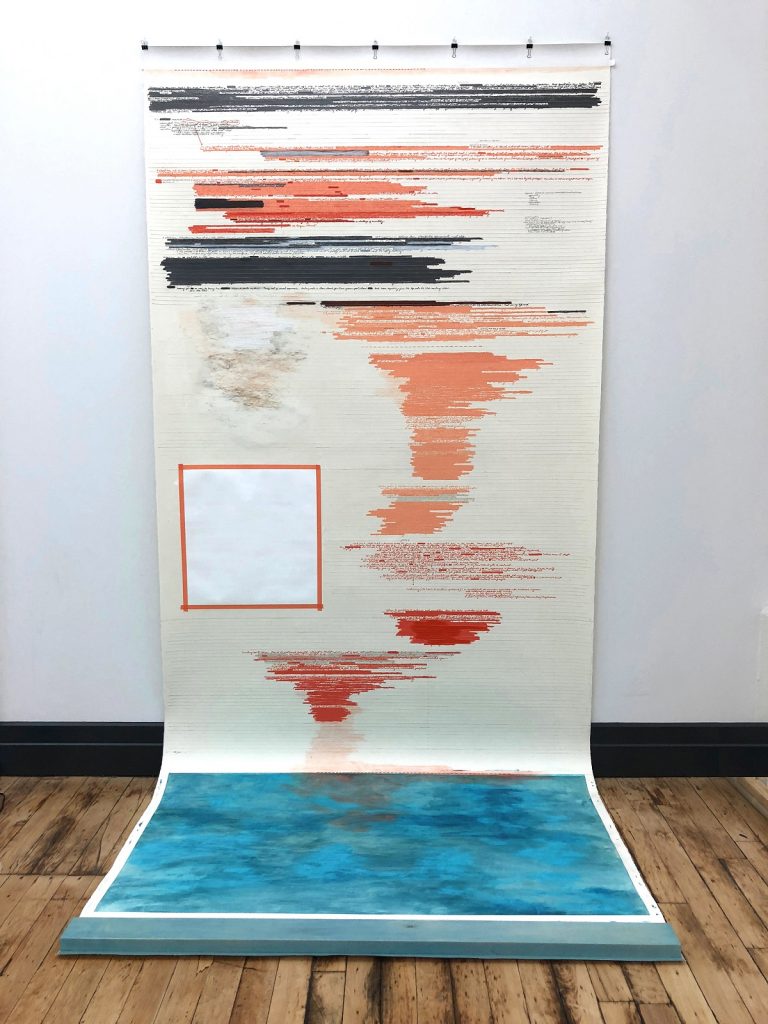

Anne Gilman’s oversized scroll “drawings” unfurl across the floor, against walls, from the ceiling, and sometimes over tabletops with a graceful ease that belies their sometimes anguished or anxious content. I put drawings in quotes because there is so much more going on here than mere lines or notations against a paper ground—taped areas, primitive diagrams, redacted written contents, suggestions of landscapes, and other elements realized in graphite, ink, ballpoint pen, and paint. “The works feel like hand-drawn maps, perhaps charting a journey through a metaphysical region,” as critic Sarah Rose Sharpe suggested in a review in Hyperallergic of the artist’s show at the Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center in 2018-19. “Gilman [evokes] a sense of passage, navigation, documentation, and landscape.”

Though she has been studying and teaching art for more than four decades (currently at Pratt Institute in New York), Gilman says she didn’t start hitting her stride until 20 years ago, when she first started using text in her work in the midst of a difficult transition. “My first marriage ended, I was looking for a new place to live and I wondered what sort of upheaval I had brought upon myself,” she recalls.

The intensity of that period acted as a catalyst for rethinking how she approached her work. “I began writing to understand my role in the breakdown of this relationship. The process yielded work that became a hybrid of writing and drawing, where text and image are used interchangeably as a way of processing personal, political, and social concerns.”

This process continues in her most recent work, where you can see between often-redacted content, the writing “about whatever is on my mind,” she says. “So it’s a mixture of what’s going on politically, or with my daughter, or my mother, while she was still alive,” she explains. “All of those things would wind up being intertwined in a way that echoes how our thoughts unfold during the day.”

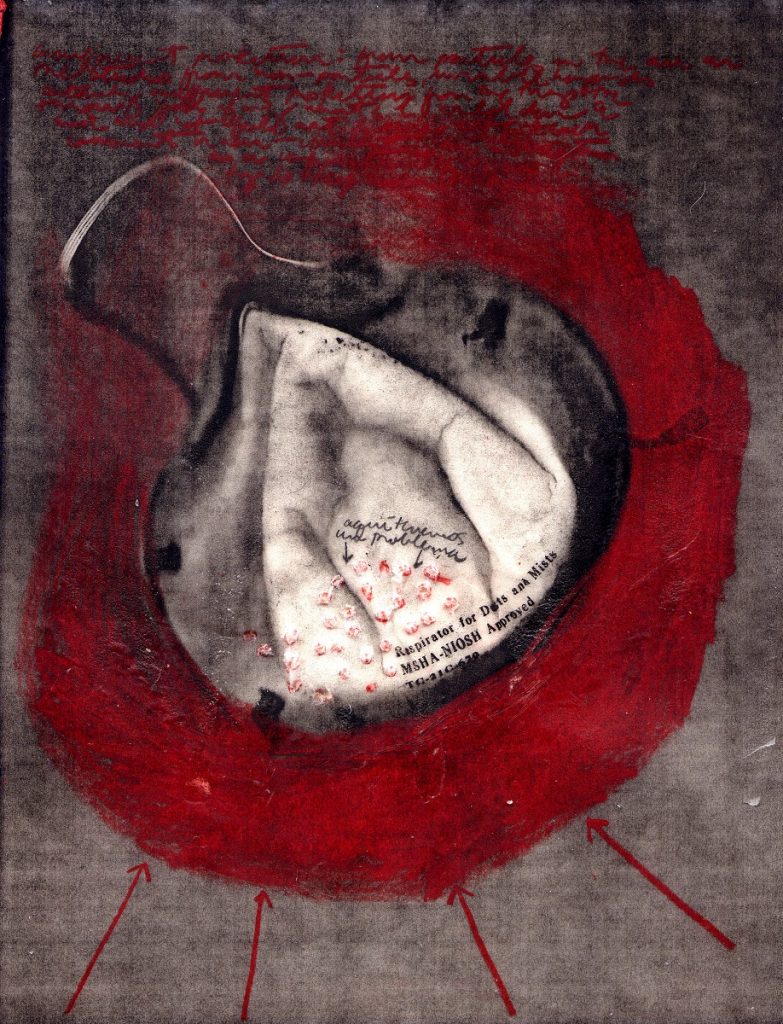

In 2004, Gilman was invited to have a solo show in Havana and had to find a way to travel with the work, which led to making drawings that could be rolled up and carried in a hat box. The series, called “Insufficient Protection,” incorporated dust masks punctured with holes, water bottles and photos of cigarette butts. The underlying idea, she says, was the “absurdity of believing we could ever protect others.”

The impulse toward using the scroll format came in part from a visit to her acupuncturist, who uses the sort of translucent paper that many doctors unroll over examination tables. It seems very thin but turns out to be quite resilient. “I liked the idea that fragility and strength can co-exist, that one can be sensitive, vulnerable, and strong.”

Later, when she wanted a heavier stock paper to add more physicality to her drawings, she started using a paper from England that she continues to use today.

“The first thing I do is to rule lines across the page with a really hard pencil so that it dents the page slightly,” she says. Gilman claims the text that emerges is not truly “diaristic,” but incorporates incidents and thoughts that flow during the day that give what can be deciphered as a stream-of-consciousness feeling.

She recites, as an example, some text from a piece called Sundowning, a term used to describe a neurological condition in patients with dementia, occurring in the late afternoon or early evening—something her mother experienced. The writing begins with a description of Gilman falling to the ground and the thoughts that mishap brought up, followed later by receiving a distressing call from her mother:

“One minute you’re standing, walking and the next minute you’re falling flat on the pavement, middle of the street… It could have been way worse, some kind of warning: It can all change in an instant,” reads one excerpt. “Is my mother’s willingness to share her agitation, to ask for comfort, finally her ability to break through the pretense that everything is fine? At 95 my mother can no longer pretend. She is no longer embarrassed or ashamed of experiences or fears. No longer trying to prove herself. Things are what they are with her.”

When she is writing, Gilman puts herself quite literally in the center of the work: she rolls out the paper and sits on top of it. “I want to be inside the work,” she says. “I want to close off other people’s ideas of what the work should or shouldn’t be, and the way for me to do that is to be immersed in the page.” Afterward she will go back and use graphite, colored pencil, or tape to cover up those portions that seem to her “redundant or unimportant.”

This place/this hour (2019), colored pencil, graphite, ink, and washi tape on mulberry paper, two sides of a scroll drawing, 321 by 27 inches

Nothing in Gilman’s background really prepared her for a life as a serious fine artist, which may in part explain why she is a late bloomer. She grew up in Queens, the daughter of a pharmacist and a homemaker, and calls her childhood “a careful and proscribed life. You didn’t think beyond the world you lived in.” She went to the State University of New York at New Paltz, originally to study art education with the end goal of teaching, but after a couple of studio courses she switched her major to fine arts. She married at 20 and had a daughter several years later. It was not until she went to Brooklyn College in the early ‘80s to study for her MFA that she found an artist who could serve as a real role model: the legendary sculptor Lee Bontecou. “She was the first woman artist I studied with. As an undergrad, all the instructors I had were male.”

Gilman says that her belief that politics affects us all on personal levels have an impact on her art. A piece called Boiling Point from 2018 started off “dealing with anger that arose in me over a stupid thing—someone was late for an appointment, causing me to lose a studio day. On top of that I got upset that I’d lost my equanimity. So I was angry about being angry.” In the course of writing about these emotions she realized that “we don’t have a healthy outlet for anger in this society. There is a need for an appropriate outlet to defuse and address the intensity, before it erupts in explosive ways.”

The title of a recent show in Connecticut sums up many of the underpinnings in Gilman’s art: “In any one day, how all the things get mixed together.”

“I want to cover the whole gamut,” she says. “I use my own experiences moment by moment to try to do that.”

Top: A corner of Gilman’s studio

I very much enjoyed this account of Anne Gilmans work .Anne was my professor and tutor at SUNY Purchase nearly 40 years ago and has been a constant source of inspiration to me. She not only taught me about the technical processes of lithography but also the importance of making work that was true to myself.I admire her work greatly and respect her as a serious artist and person who is constantly analysing and pushing the boundaries of her art.

I am very much in awe of her as an artist and a person, and proud to have her as a treasured friend .

I love this article—really resonated with me, so interesting to hear about Anne Gilman’s trajectory and process. I wish I could get up close to read some of her writing too. Having gone through the process of dementia with my Father and both in-laws, I can really relate. I also love the way in which Anne’s problem solving for transporting work to Cuba by rolling drawings in a hat box led to a whole new way of working!