Using the computer to translate technology into art

The first time I paid serious attention to the role computers might play in contemporary art was in 2012 (a little late in the game), when I saw the Whitney Museum of American Art’s solo for Wade Guyton, then 40. The artist was described by New York Times critic Roberta Smith as “both a radical and a traditionalist who breaks the mold but pieces it back together in a different configuration. He is best known for austere, glamorous paintings that have about them a quiet poetry even though devised using a computer, scanner and printer.”

Frankly, I was underwhelmed. It seemed to me Guyton was simply borrowing strategies from Andy Warhol, Richard Prince, and even Mark Rothko and then simply spitting them out on a large scale through a state-of-the-art printer. I’m one of those sad fogeys who really enjoys seeing the touch of the human hand, so I have since then by and large ignored any work labeled “digital art.”

Until I started noticing the number of Vasari21 artists involved with computer technology of all sorts—and producing work that’s both intriguing and gorgeous. I can’t pretend to understand all the processes they use, since it’s about all I can do to enlarge and reduce photos on the screen (and please don’t ask me what “dpi” means). So I’ll be presenting their accounts, in their own words and pictures (and sometimes sculpture) in two parts, beginning this week.

P.S. The title of this post is borrowed from Tracy Kidder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book,The Soul of a New Machine, which chronicles the experiences of a computer-engineering firm to design a next-generation model in the 1970s. Ann Landi

Laura Figlewski

My first computer was a cutting-edge Mac IIFX. It came with Photoshop 1.0 and a whopping 50-megabyte hard drive. I wasn’t afraid of the computer, and enjoyed learning something new, but I was initially skeptical as to whether or not it was an improvement on doing things by hand. As a graphic designer, I was used to touching and drawing and cutting.

Laura Figlewski, Lurch (2018), photography, acrylic mixed media, steel rods, on felt, triptych, approximately 45 by 70 inches

Almost 30 years later, working on the computer is as natural as breathing. But when it comes to using it as a fine-art tool, once again, it’s a source of ambivalence.

A few years ago, I started taking abstract photos and using them as the main elements for a series of mixed-media pieces. The composition begins in Photoshop. Then I print out images. Other materials, ranging from paint to plaster of Paris, are added and I see where things go from there. These pieces have been enjoyable to create and are hands-on enough to feel like I’m “making something.” Still, I haven’t been able to shake the feeling that by using photos and the computer rather than drawing or painting, I’m cheating, or taking the easy route, or not making real art.

It isn’t that I can’t draw and paint. And I certainly consider photography art, but don’t consider myself a photographer. My photos are like raw materials or reconnaissance photos. I use them, along with the computer, to search and create. These tools let me try things and compare alternatives without wasting materials, and this method of creating imagery flows for me.

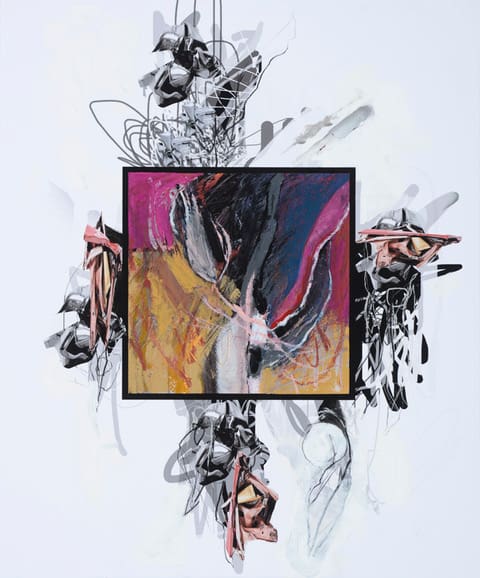

Laura Figlewski, Outside Eclipse (2017), photography, acrylic mixed media, steel rods, on paper and felt, 41 by 36 inches

Even the line between the camera and computer is a bit blurred. I take most of my photos with my iPad which isn’t exactly a camera or a computer.

Perhaps some of my unease is due to life experience. Like the artists who once ground and mixed their own paints and then had to come to terms with commercially made paint, I can easily recall a time when the computer was an alien object for making art.

But in the end, I will push through this self-constructed creative barrier and keep making art with whatever tools do the job.

Kim Thoman

I use a computer in three different ways in my artwork.

1) As a tool for designing shapes to be printed in three dimensions. I design the shape, and an expert reproduces it in the software Cinema 4D, so it can be manipulated in the computer in the round. Then it goes to a 3D printer to print out the actual piece.

As a painter, however, I’m interested in color and the surface texture or decoration on my shape. So before sending the data shape to the printer, I use a digital file of one of my paintings and in the software wrap it around the shape. For example, the Bird Venus 1 shape was digitally wrapped with a detail of a digital file for Motion Series 17.

I work for hours on the computer, moving the texture (Motion Series 17) around the 3D shape, enlarging it so only a detail is used, for example. All this to make it look good from all sides and ready to be 3D printed by LGM3d in Colorado on a Projet 860 printer. But, before they print, LGM does some magic to carve the insides of the shape (on their screen in a CAD program), making it hollow so as little as possible material is actually printed making it cheaper for me.

The piece comes out of the printer with the color on the outside only. If you were to hack this hollow Venus piece open you can see from its walls that the color is just on the very thinnest outside layer. Sanding the piece on the outside would bring it quickly back to the white color of the powdery stuff used by the printer to make it. This is even harder to describe. But, no need. Check out great videos on Youtube.

It’s an expensive process as these printers cost in the hundreds of thousands, so it will be many years, if ever, before I own my own.

Kim Thoman, Shortstop Tangle 14 (2018), mixed media on paper: digital collage, downloaded and altered images, graphite, acrylic, oil pastel, 23 by 19 inches

2) To create a digital collage, of my own work that also includes digital marks to create an underprint on paper or canvas. This way I never have to start from a white canvas. An amazing and wonderful help! I own a 9600 Epson printer that can print up to 44 inches on the short side if I’m using rolls.

3) I download images from the Internet and collage them into my compositions. I love John Chanberlain’s crushed-car sculptures. So I find images of his works on the Internet, download them, alter these in Photoshop, and incorporate them into my work. For example, his pink sculptures can be seen in Shortstop Tangle 14 in the area surrounding the square. One of Chamberlain’s earliest sculptures was called Shortstop (1957).

Tm Gratkowski

Although I do not use the computer to generate a work of art, I do use it to test ideas in a kind of anachronistic way. I’m an artist who holds composition in high regard, but not many people realize that I use various technical aids to create many of my pieces, and in some cases these are similar to those employed by Renaissance masters more than 500 years ago.

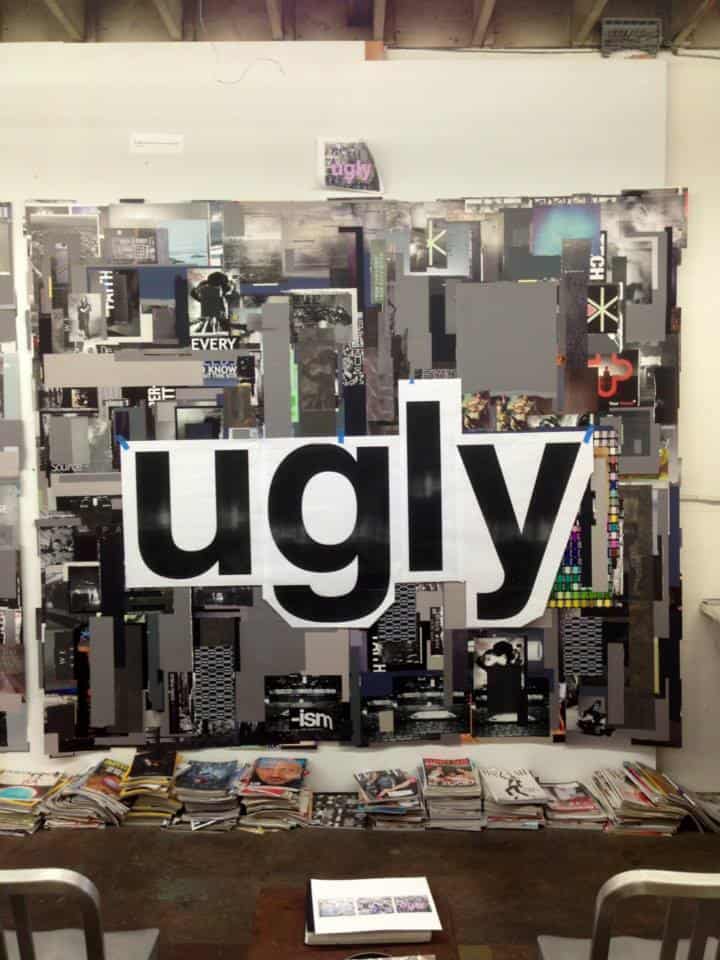

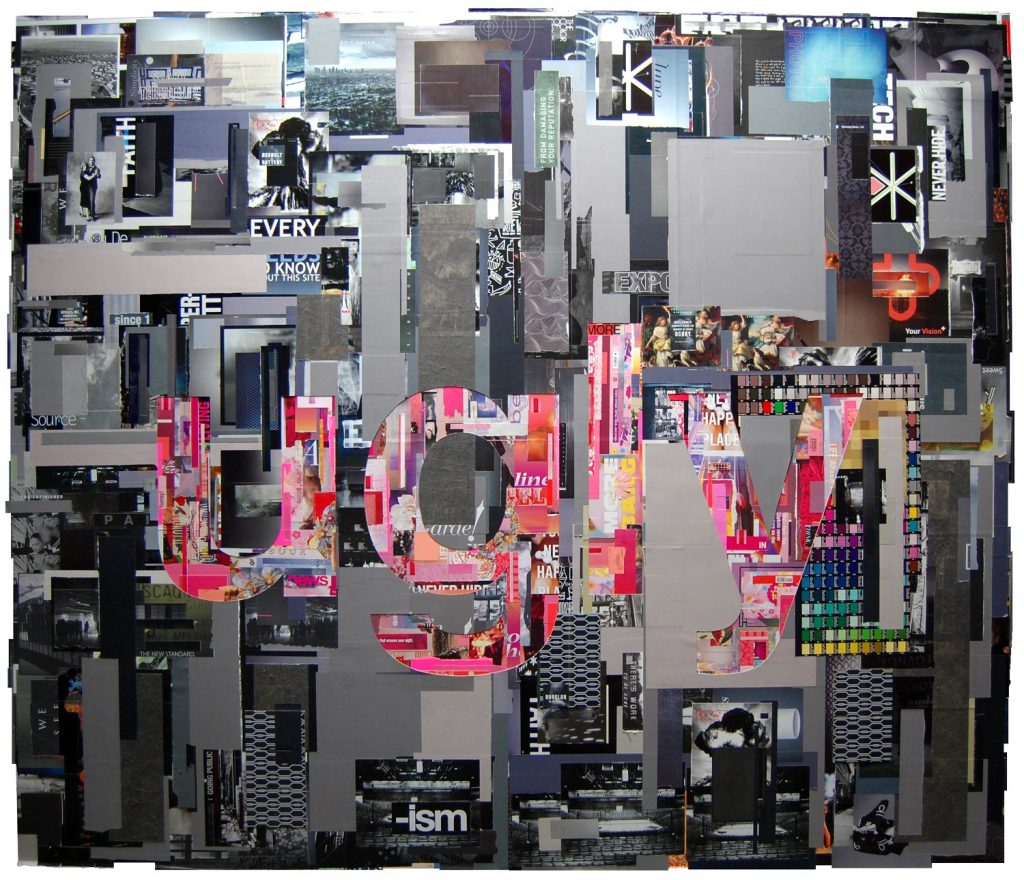

I find it helpful, for example, to hold up a grid that frames the work or checks compositional balance. A few years ago, as my pieces were getting very large, I had to develop more creative ways to see the work without compromising the progress I’d already made. I found it useful to take pictures with my cell phone while a collage was still on the wall. Then I could either look at the image on the mobile screen or send it to my desktop computer. That way I could turn away from the physical object, and then see it again on the computer screen in my office. It was almost like seeing it for the first time if I’d walked into a gallery showing one of my works.

Seeing the work in a different context allows me to assess it more critically and in a more objective way. What I soon learned after taking pictures on my phone and/or sending them to the computer was that I could begin to manipulate the work in various ways. So I began to rotate the image to see how the composition held up—in some cases I found the work was much more powerful if oriented in a different way than I had originally intended. This technique is one I use often throughout the process of creating my collages.

At times some of my pieces incorporate large bits of text or stencil-like images cut out by hand. In the case of the stenciled images, I can take a picture of the image and then another picture of the work in progress and use my computer (with the help of Photoshop) to move the image around to see where it looks best compositionally before committing to gluing it in position. I found that this technique helped in even better ways when using text as a major part of the composition. I could use my computer to change the font, the size of the text, the orientation, and even color to help me make better decisions without risking errors in the work itself.

Holly Grimm

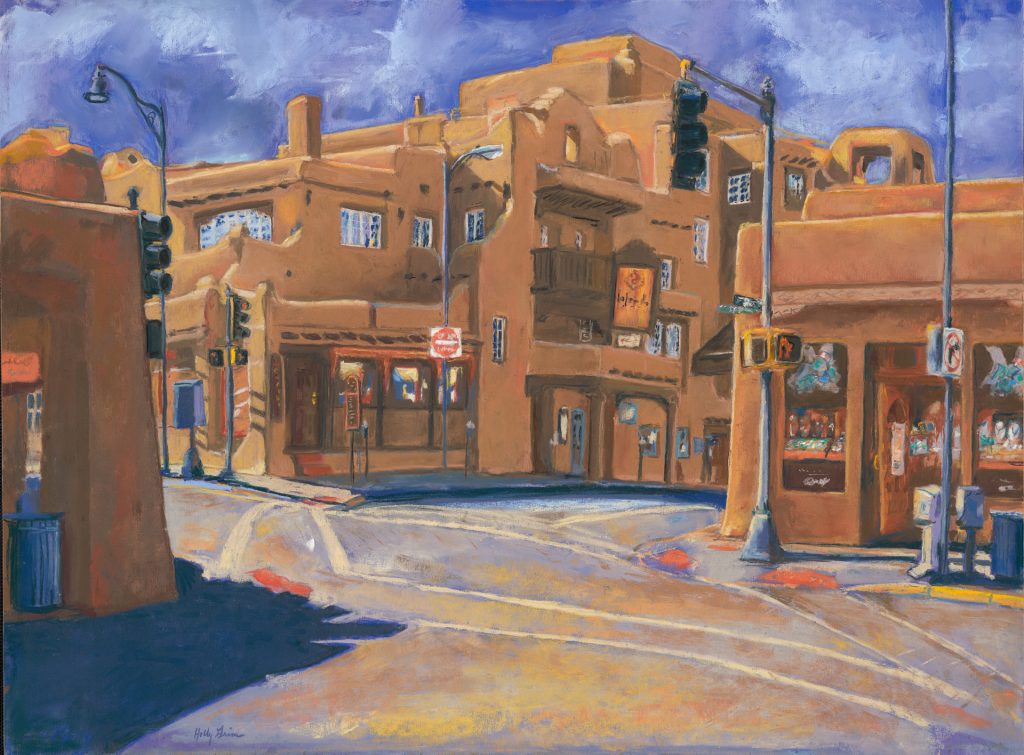

I first discovered Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a digital tool for my art practice in 2016. I had been both a software developer and an artist for many years without the two intersecting. As I began experimenting with AI, I was intrigued by the interesting patterns and painterly qualities I could achieve in the final work.

In 2018, I was selected for the scholars’ program of OpenAI, an Artificial Intelligence research organization located in San Francisco. For my final project, my mentor, Christy Dennison, encouraged me to work on something that engaged my knowledge as an artist.

I started by looking at aesthetic principles as defined by Denis Dutton, the American philosopher and media activist. From his list of seven principles (expertise or virtuosity, non-utilitarian pleasure, style, criticism, imitation, special focus, and imagination), I chose to work with style. The definition of style in this context means the rules of form and composition.

I selected the following style attributes that I learned from my art teacher: variety of texture, shape, size, or color; contrast; repetition; primary color; and color harmony.

I then randomly selected 500 masterworks from WikiArt, the online art encyclopedia, and labeled each one with values for these attributes. (For primary color, I used the cyan-yellow-magenta color wheel values. Since the values are based on my own perception, the network is a very subjective reflection of my own understanding of these attributes.)

I then fed the painting and label information into an AI neural network and trained it to recognize the stylistic attributes. The network uses multiple hidden interconnected layers of neurons to learn properties of the data. In the final step, I fed photographs of my original paintings into the network, along with target values for the attributes.

One run of the network results in the creation of several hundred images. There is a great variety of texture, color, and and form—modifications that range from bland to fascinating. Curation is a major undertaking as it’s easy to become overwhelmed with so many related, yet chaotically diverse, images. And yet, sometimes the AI appears to discriminate and find previously unseen patterns in my work.

Jonathan Morse

In some ways I’m not the best spokesperson for this subject, as I swim in the very shallow end of the digital pool. Today’s VR and AR artists, who use interactive methodologies, think my work is hopelessly quaint, so 2005 (or maybe even so 1990s). The Museum of Modern Art has a new art and technology show up now, and I’ll bet you won’t find a paper print anywhere. I’ve often said that anyone with a semester or two of Photoshop 1 can easily do what I do technically, being completely self-taught, but in many ways my lack of technical expertise frees me to experiment and be imperfect.

I was trained in semi-traditional printmaking, photo-silkscreen, and photo-lithography, but those toxic days morphed into digital printmaking with a hiatus, a period when I assumed I had missed the digital bandwagon. But I just started to fiddle and play, back when Iris printers cost $100,000 and only service bureaus could have such expensive equipment. As the price of pigment printers came down, thereby democratizing the inkjet-print world, at first I outsourced some printing but came to realize that notwithstanding all the technical traumas of doing your own work, that was the only way for me to control color and compose in the iterative way I have developed: building an image from nothing on the screen in waves of inspiration, perspiration and struggle toward something new. For me it’s become a craft, and not an easy one for a non-technical person.

Using my computer and Photoshop allows me to create, draw, paint, and combine as a cyborg artist in ways I would never be able to do otherwise, in just a small extra bedroom. My iMac and I are collaborators and Photoshop is my avatar, taking my hand and guiding me through the digital divide. Photoshop was invented as a “digital darkroom,” as a way to make the sky bluer, remove the telephone pole, bring out the details in the shadows.

From my perspective these wonderful tools designed to improve a photograph can be used at cross-purposes—to create rather than to perfect. But because I am working at such a low level of technology I do worry about the future: will I even be able to keep up, and will anyone even care about my lifelong devotion to Ink on Paper?

So for me it’s all just another pencil, taking its place in the history of human mark-making. Use of a computer as an artistic tool is not an end in itself but a tool to grab on to at various levels of competency. The world is full of super-skilled technicians, but what is important is the work itself, its texture and insight, not how it was made. Everyone’s an image-maker now and so as artists we need to bring something new and more to the table. Artists have no special claim on creativity except where we take it to evolve, delight, and question. As I have so often said, why make an image that’s been seen before?

Top: Laura Figlewski’s studio with work in progress

Many thanks for including me in this article Ann, and I enjoyed learning how others are integrating technology in their work. Can’t wait for Part 2!