Earlier in the week, I tried to imagine what kind of responses I would have gotten had I posed that question to one of the great masters of the Renaissance. “Signora,” I can hear Maestro Buonarrotti explaining, con pazienza, “a drawing can be many things. A quick sketch in a notebook, a study for drapery, a highly detailed rendering of the figure, an exquisite silverpoint portrait. You can even use a full-size cartone and transfer an image to a wall for frescoes by pouncing chalk dust through tiny holes….that is a drawing too!”

And I would have to respond, “Ma, Caro Divino, non è veramente molte cose,” even as I begged him to excuse my miserable broken Italian. “Look at all that artists call drawing today. They still use pencils and chalk, but there is this thing called collage, originally put into the mix by these French guys Picasso and Braque, and there are drawings made by using a Dremel on Plexiglas, and you can even draw on the computer, una macchina that made some people richer than the Medici….”

And I see the Divine One scratching his head. “Una macchina? Era inventato di Leonardo?”

“Allora,” and here I hold out my arm to the scruffy genius, “potremo parlarne a pranzo.”

“No, non ho tempo per questo!” he cries in anguish. “Devo finire la capella Sistina!”

Below, some samples of what artists call drawing now.

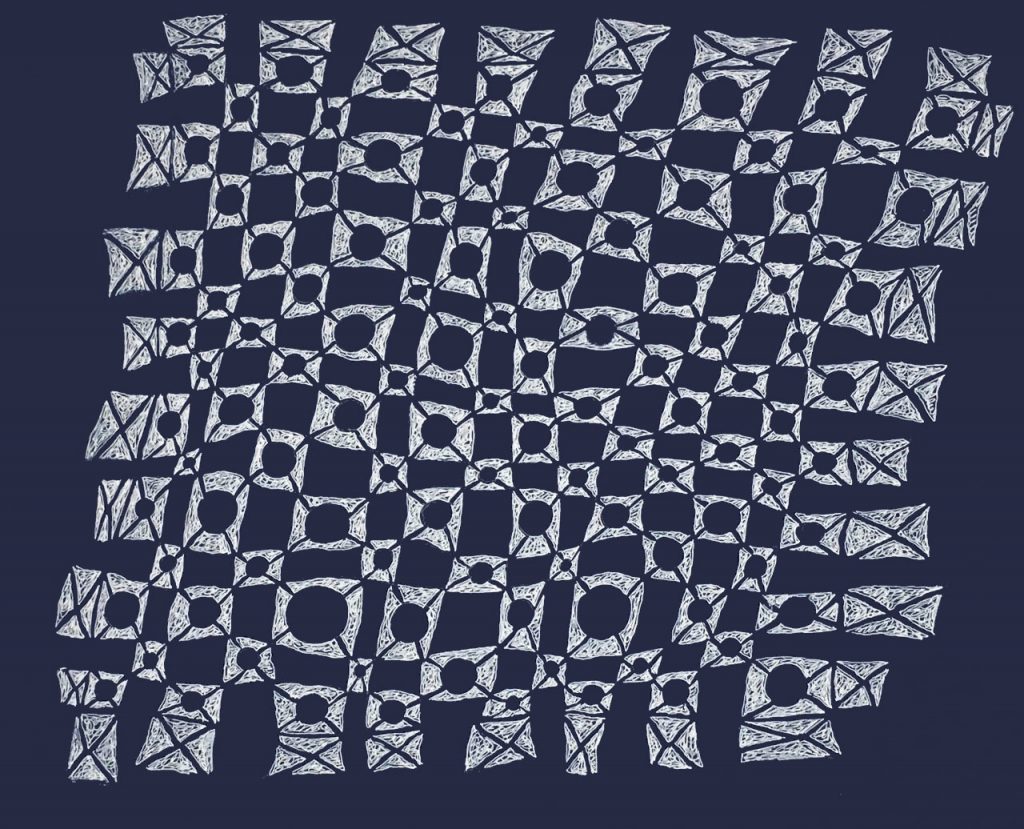

Jonathan Morse

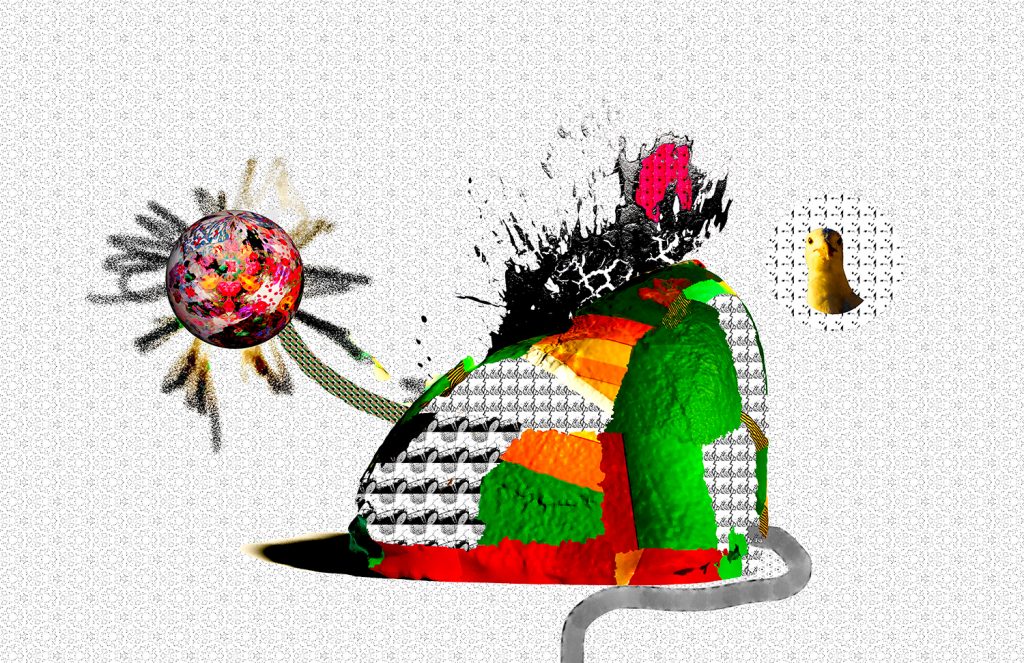

I have been obsessed with drawing lately, the pulse of which has upticked in the last few years—via analog and digital marks, often in concert with and in contrast to each other. It’s something about handwork, even where the hand grabs a mouse or a drawing tablet to enter the digital divide: drawing hardwires us to the network of the soul. Or less portentously put, it provides direct input from the unconscious to the image itself without the intermediary of overly-thought-out decision-making. Does it change the world? Maybe not, but it does expand our potential to interlineate our daily lives and to see connections previously unrealized. Why make an image that’s been seen before? Drawing is literally how we make our mark.

Caprices 4 (2019), limited edition pigment print, printed by the artist on Moab Juniper rag, 24 by 36 inches

Teri Donovan

Drawing has been important to me since childhood as a way to know and understand the world. Until recently, that meant examining the physical world to understand form, shape, value, and color through drawings from life. But contemporary drawing has expanded to encompass many areas not included in traditional notions of drawing. Mark making, however, has always been an essential aspect. In this drawing, marks are made by dipping string into ink which is then dragged across paper to create lines and shapes. The cut-out lines and shapes are placed on handmade papers chosen specifically for textures that simulate lines, marks, and values. I think of these as ‘found’ elements of the drawing. Collaged together, these elements combine to complete the composition.

Andra Samelson

A day in my studio often begins with drawing, an activity that helps me to focus and sharpen my thoughts, providing me with an open line (pun intended) to my unconscious. My drawings are instinctive and improvisational and show the traces of their evolution.

Recently I am engaged in bringing these immediate qualities of drawing to the process of painting. Using various tools, I scratch, swirl, layer and draw into paint, spontaneously creating intersecting webs of linear markings.

I often think of the French writer René Crevel’s observations: “Straight lines go too quickly to appreciate the pleasures of the journey. They rush straight to their target and then die in the very moment of their triumph without having thought, loved, suffered or enjoyed themselves. Broken lines do not know what they want. With their caprices they cut time up, abuse routes, slash the joyous flowers and split the peaceful fruits with their corners. It is another story with curved lines. The song of the curved line is called happiness.”

Tracy Linder

As a sculptor, I rarely sketch my ideas. I have hundreds of pieces of paper with ideas written on them, but not many sketches. When I do draw, it is for its own completeness. I have a heavy foundation in drawing and love what the simplicity of a line can communicate. My work always entails time and scale, so I enjoyed translating those elements into this drawing.

For this image, I had several photographs of the cow, and worked from those and from my own memory, and did my best to let the drawing have a life of its own so it kept its freshness. I knew the most important thing was to maintain the skeletal and muscle structure in order for it to make sense.

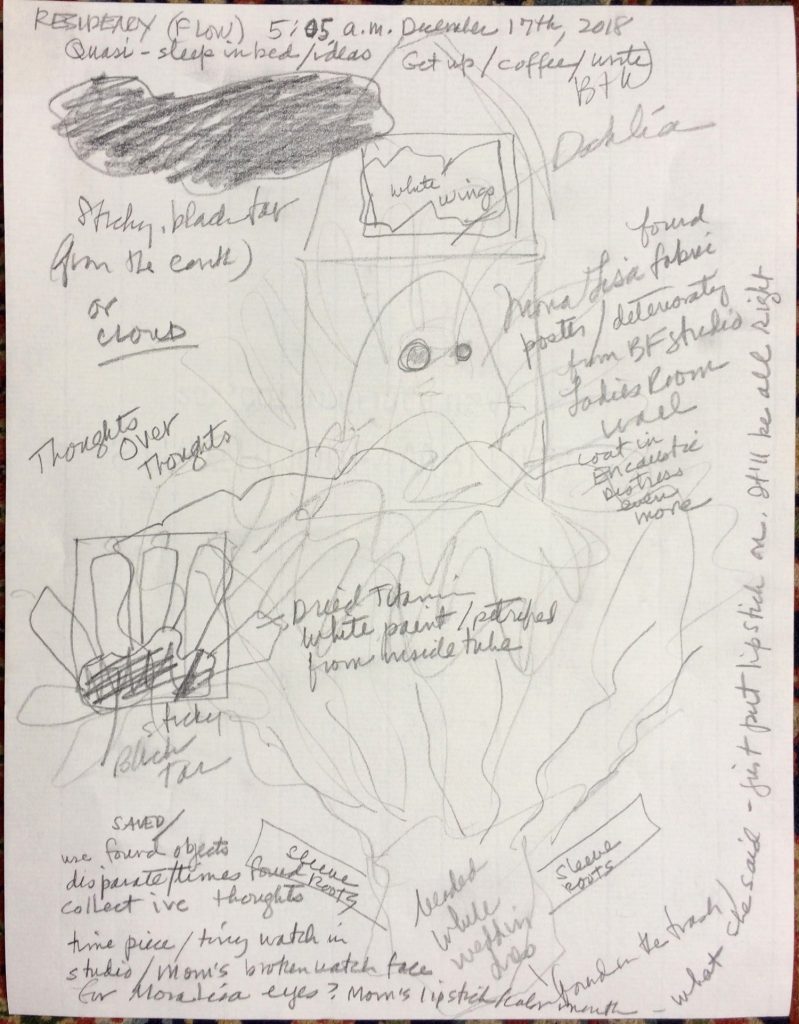

Beverly Rippel

I often picked up a pencil to draw pictures when I was very young, and in later years to make preliminary sketches for big paintings. In fact, I often told my students a true story about my dentist dad extracting four of my lower front baby teeth when I was about seven years old. He had given me plenty of Novocain, but to ease any discomfort (I think his own), he took me to the local drugstore and said, “You can have anything in this store that you want!”

I chose a yellow paper box covered in clear cellophane, revealing 16 Number 2 pencils. I was thrilled! To this day I still find I use a Number 2 pencil to draw or record creative thoughts on future projects that come to me in the wee hours of the morning before they slip away while I am still in half-sleep. There is such immediacy about using a simple pencil. Here is an example of fast and furious thoughts spilling out onto a piece of computer paper from December 17th, 2018 at 5:05 a.m. They are notes and sketches about a possible upcoming artist’s residency.

Peggy Klineman

I recently started hosting drawing sessions in my studio on Sunday afternoons. Three other artists joined me for what I hope will be a weekly event. I am open to how the afternoon is structured, so everyone can share in working from a model and doing what they want to accomplish.

I continue to draw from the model because I love doing it and I find no better way to keep my eye sharp than looking at and drawing the many nuances and subtleties of the human figure. When I am working abstractly, my vocabulary is greater because of the references I have from drawing the figure. My hero and one of my favorite artists, Richard Diebenkorn, always drew the figure among other things. I guess I model (pun intended) my practice after him.

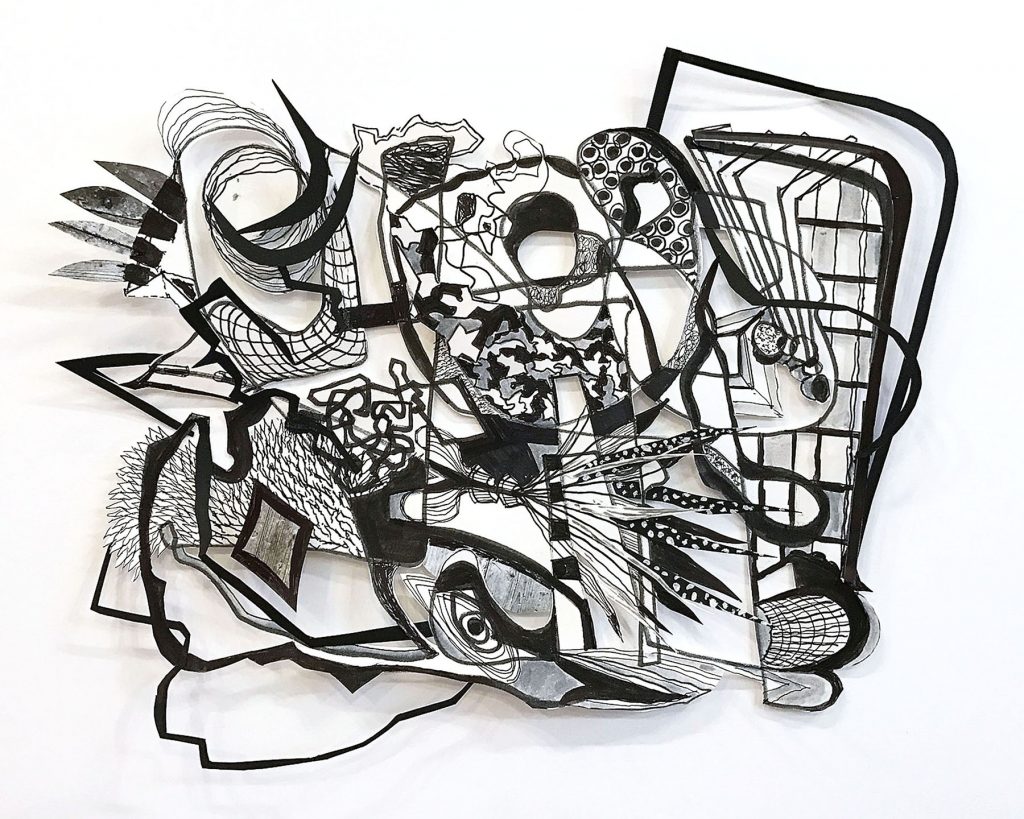

Karen Snouffer

Drawing represents movement for me—as an extension of the body and a statement on how line moves through space, even as we follow it on a two-dimensional surface. Arcade is a jagged, jazzy, architectural statement about a fantasy space. I cut out the drawing and pulled apart some elements to become low relief, to play with and encourage the tension between flatness and dimension. The viewer enters a space with curving, looming beams overhead, clinging to them, while being confronted by the beauty of chaotic patterns and paths. There is little likeliness for escape, even though she can see outside, through the stable grid.

James Deeb

I’ve drawn for as long as I can remember. It’s a common thread winding through my artistic practice; from my paintings and monotypes to my short videos. My sketchbook pages are peppered with many false starts. That’s fine. These missteps often lead to a refinement or a completely new idea. As an activity, drawing is immediate and open-ended, like having a free-form dialog with myself (even if I sometimes stammer or spout gibberish). I try to keep this sense of exploration in my more finished drawings, although I clarify my ideas as the dialog now includes the viewer as well as myself. If I were a musician or a writer, I would still draw. It’s that indispensable as a tool and a process.

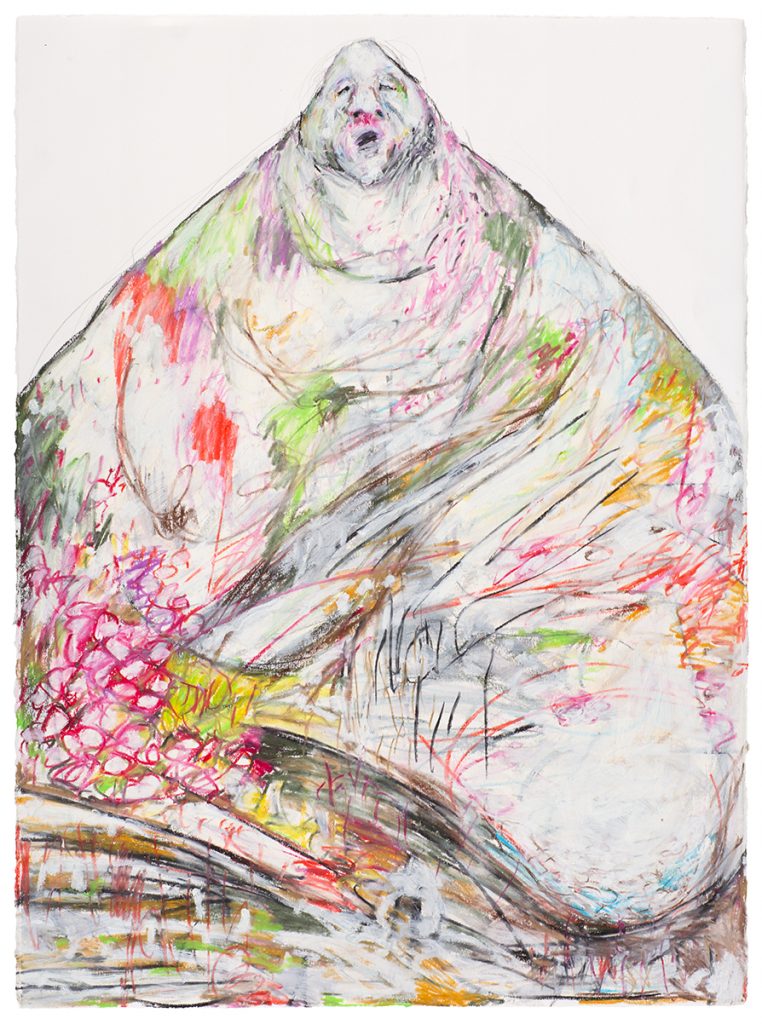

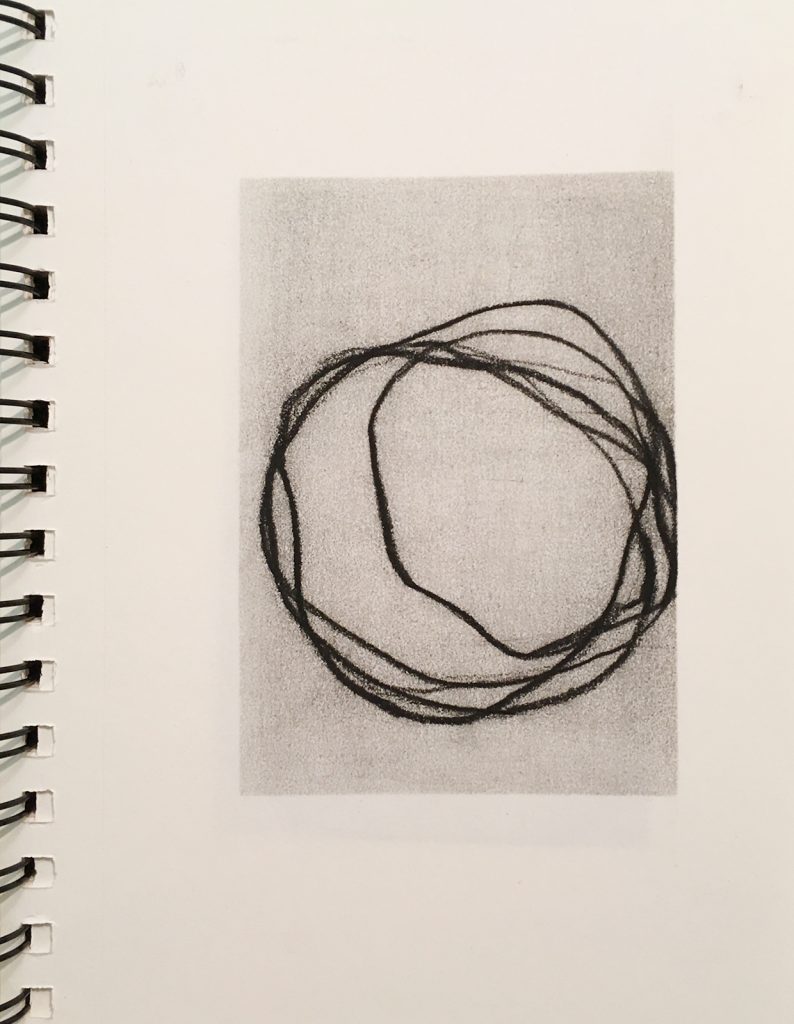

Tamar Zinn

My drawings serve as an unmediated record of wordless thoughts, emotions, and gestures. The act of drawing is all about taking risks and it is where I feel most exposed as a visual artist. Unlike my paintings, which I can fuss over endlessly, the drawings are completed more quickly, and I accept the marks I’ve made without making revisions. But that is not to suggest that my drawings are dashed off. Whether I am working in a bound sketchbook, or on large sheets of drawing paper, I generally begin by defining and toning an area of the paper. After the field is established, I start somewhere with a mark and see where it takes me. If I am intrigued by where the drawing lands, I feel compelled to make another, and another, until I exhaust the possibilities it has offered me.

Donna Fenstermaker

Every winter I seem to be attracted to drawing or painting trees; sometimes I also call them sleeping trees. In winter, with little or no leaves, they reveal their structure, sometimes organized, sometimes wayward. They can be like musical exercises, or like jazz. The composition comes first; in the tree pieces, it’s the lyrical movement that separates positive and negative space. When that is found, I begin for me the meditative space of inking. The ink pens are many, new ones are Sailor pens from Japan with refillable ink cartridges, micron pens of varying sizes, and others. I am a fan of pen nibs dipped into liquid ink, but this paper is too soft a surface to drag needles across.

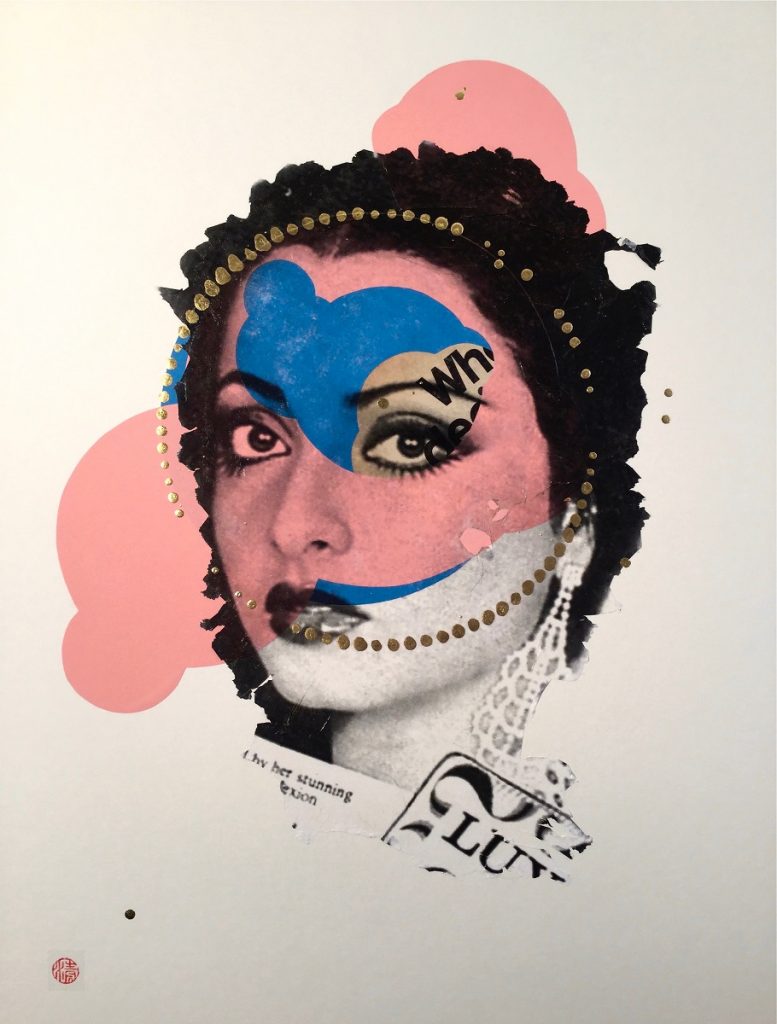

Blythe King

My drawings start out as images of fashion models found in old American mail-order catalogs, most notably the bra ads. Through a manual photographic transfer process, I alter these images by hand with the aim of revealing that women are gods. I especially love this process for the way it results in a transparent image, but also for the expressive rips and eroded edges it produces. It is not until I complete the transfer that I begin to combine elements of collage and calligraphy. At this point, all kinds of new lines are formed by cut paper, layered materials, and the way I use gold leafing. There’s a spontaneity and energy to the calligraphic dots and circles that capture revealing blips in the universe.

Top: Tracy Linder drawing Cow’s Eye at her studio in Billings, Montana