Born in Shanghai and raised mostly in Hong Kong, Mimi Chen Ting grew up at a time when traditions were still so strong that her grandmother hobbled around on tiny bound feet and her mother was the concubine of a prosperous banker (her parents married when she was in her twenties). An interest in art started in convent school. “Every Christmas we had to make a lot of decorations,” she says. “I knew I could draw. I liked to make lines.”

By the time she finished high school, she was eager to get away. “If I didn’t leave home I’d suffocate and die.” A boyfriend took off for Australia, and Ting was all set to follow him, but instead she moved to California to attend the San Francisco College of Women (now part of the University of San Francisco). “My mom actually cancelled my registration after I was accepted because she didn’t want me to leave home,” recalls the artist. “I had to call my father, who was working in Malaysia, and he came home and put me on the plane.”

Ting studied sociology and English literature but after a year of field work realized she would make a “horrible social worker.” She transferred to the state university in San Jose, where she studied with watercolorist Eric Oback, who urged her to find her own way as a painter. “I realized I couldn’t deal with watercolor,” she recalls, “so I used acrylics and it’s been my chosen medium ever since.”

A year after graduation in 1969 the artist had the good fortune to land a show at the Lucien Labaudt Gallery in San Francisco. The intrepid young painter then wrote to Thomas Albright, art critic at the San Francisco Chronicle, and invited him to have a look. She ended up with a review in a column that also included Jasper Johns. It all seemed fast and easy, but other galleries were not quite so encouraging, telling her to come back in a few years. “I didn’t understand the system,” she says now.

Ting married right out of college and within a few years had two children. While pursuing a graduate degree, she rented a studio in downtown San Jose and would take the kids with her until one day she feared they’d crawled out a window (they turned up under a table). Eventually the pressures of raising children and pursuing an art career led to giving up the studio and, for a time, painting. She turned to performance work instead, at the urging of the university gallery’s director, and became part of a small troupe that would take over abandoned buildings to do site-specific pieces involving projections and movement. “Sometimes we had an audience,” she says, still sounding a little astonished.

By 1981, though, Ting had her MFA in painting and was one of the founding members of a modern dance troupe. She was also teaching drawing and design at the college level.

In the late 1980s, a few years after her father’s death, her older brother died suddenly, provoking a crisis that most likely had its roots in the sexist nature of Chinese culture. “When I went to the funeral, I really felt my mother would have preferred that I had died,” she says. “I believe she could not help herself; she didn’t have the choices I did.” She wanted to “take a leave of absence from family life, from everything,” and so her husband, who was working as a material science engineer at the time, asked, “What’s the last thing you’d like us to do together?” They took a train to Santa Fe for six days to see five operas.

On a side trip 75 miles north to Taos, NM, Ting woke up in an inn in the downtown historic district “absolutely sparkling,” as Andrew noted. He told her, “If this is the place for you, you’d better do something about it.” And so after breakfast the artist went to see a real-estate agent and within two hours found a one-room house, telling herself, “This is where I’m going to grow old.” A year later she added a studio to the property, and she and Andrew eventually bought a neighboring lot and built a larger studio and house to accommodate visits from her children and grandchildren (the “leave of absence” from family life, of course, was never permanent). On her website, Ting notes that she derives “continuous inspiration from the ever-changing vistas, uncompromising grandeur and spectacular weather patterns of the high desert.”

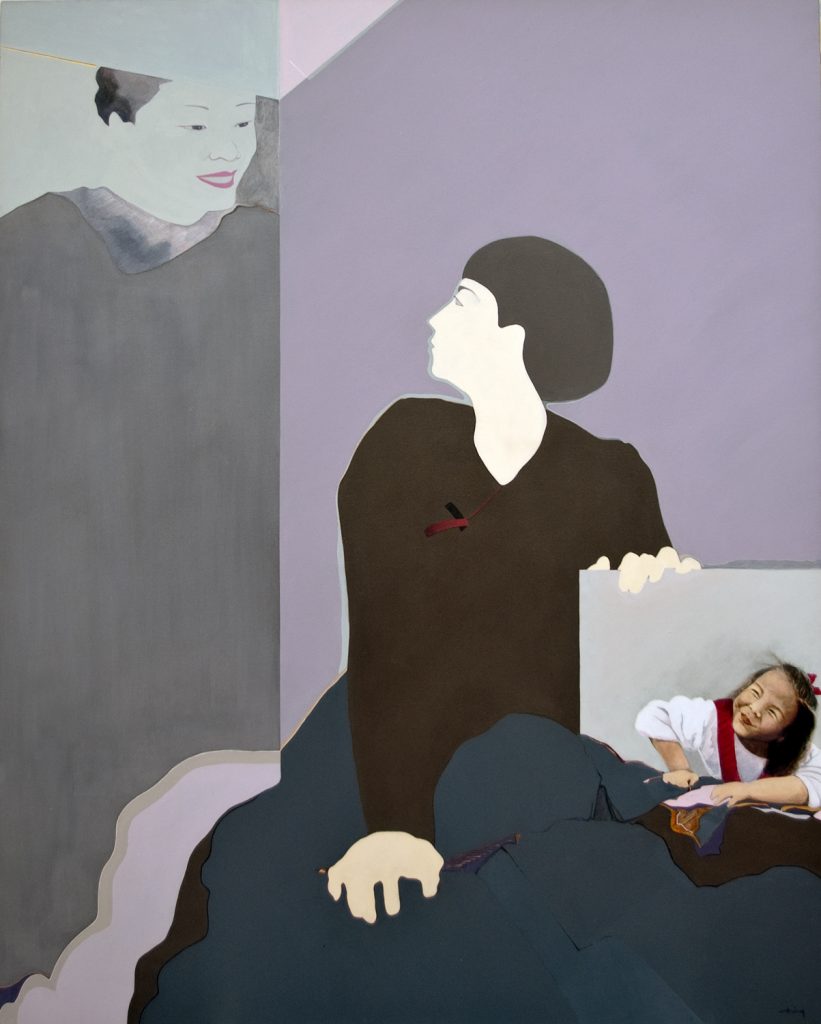

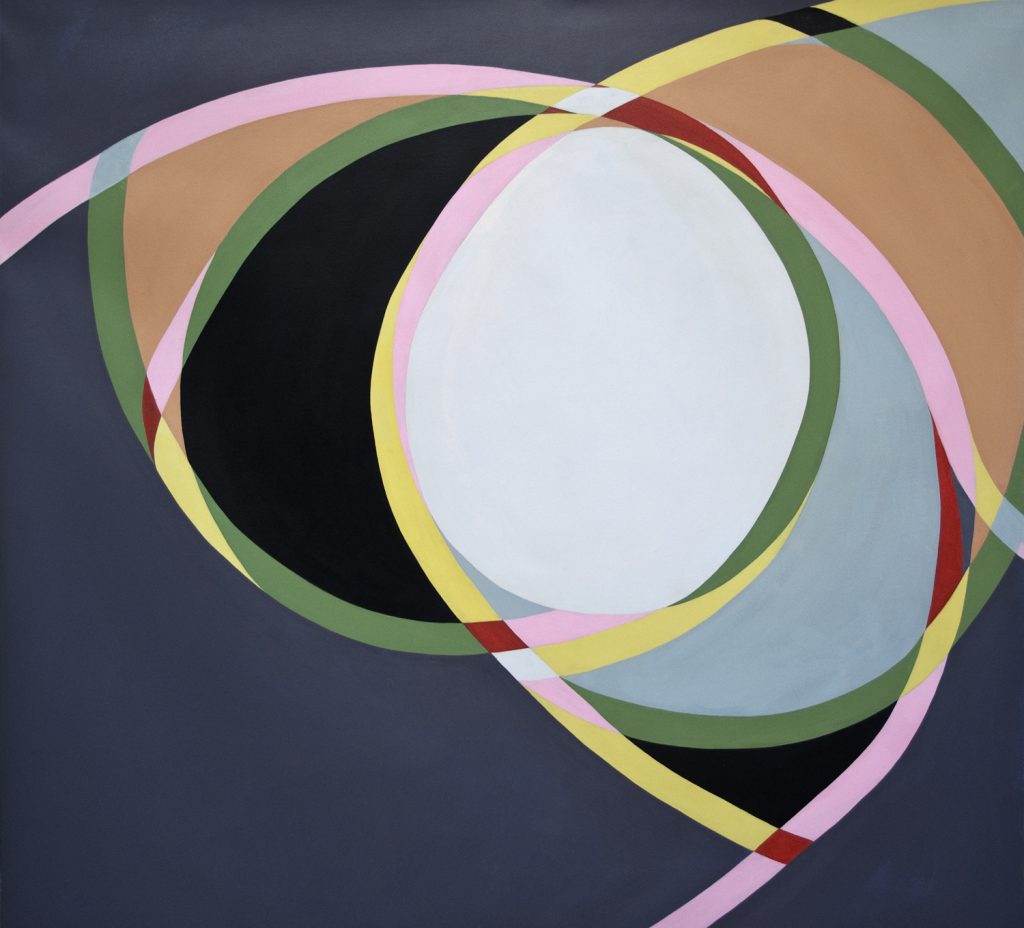

Until the mid-1990s, the artist’s work followed a distinctly figurative bent, although the imagery was always highly abstracted even if the subjects were autobiographical. Her paintings of the last two decades revel in a lyrical vocabulary (one reviewer noted a resemblance to late de Kooning) and a color sense that pits unusual hues against each other (Easter-egg pastels paired with robust earth tones, for example). Her performance pieces have occasionally drawn on a rich life history, in which the Asian past haunts her Western identity, as in a piece called “Ghosts Revisited” (2005). As performed at the Harwood Museum in Taos, photos of her grandmother at age 59 offered a backdrop to the artist at the same age.

“Basically I see no division between painting and performance, except in the tools—the body for performance, art materials for painting—and manner of execution,” the artist says. “The expression is the same in that they both spring from an inner need to be heard, require a stringent devoted practice, a clarity of intent in the use of space, and a succinct delivery of content. I see my performance work as complementary to my two-dimensional work, a way of bringing three-dimensionality and real time into the equation.”

Mimi Chen Ting in a performance of “Ghosts Revisited” at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, NM, 2005

Ting says she feels she’s in a very good place right now. She divides her time between Taos and a studio and home in Sausalito, CA (which she finances using a “simple strategy” to make money off the stock market—“I’ve been blessed with a good head for numbers,” she remarks). And she’s had shows recently at Vedder Price in San Francisco and Jen Tough in Vallejo, CA.

“My work does not fit easily into boxes,” she notes. “All my work is expressive of an inner self.”

Ann Landi

Such beautiful and luscious work. I’m sure the surfaces are astounding in person.

Wonderful interview/article with Mimi Chen Ting. Thank you!

Go Girl—-