How to get a grip when a work of art leaves you almost speechless

By Millicent Young

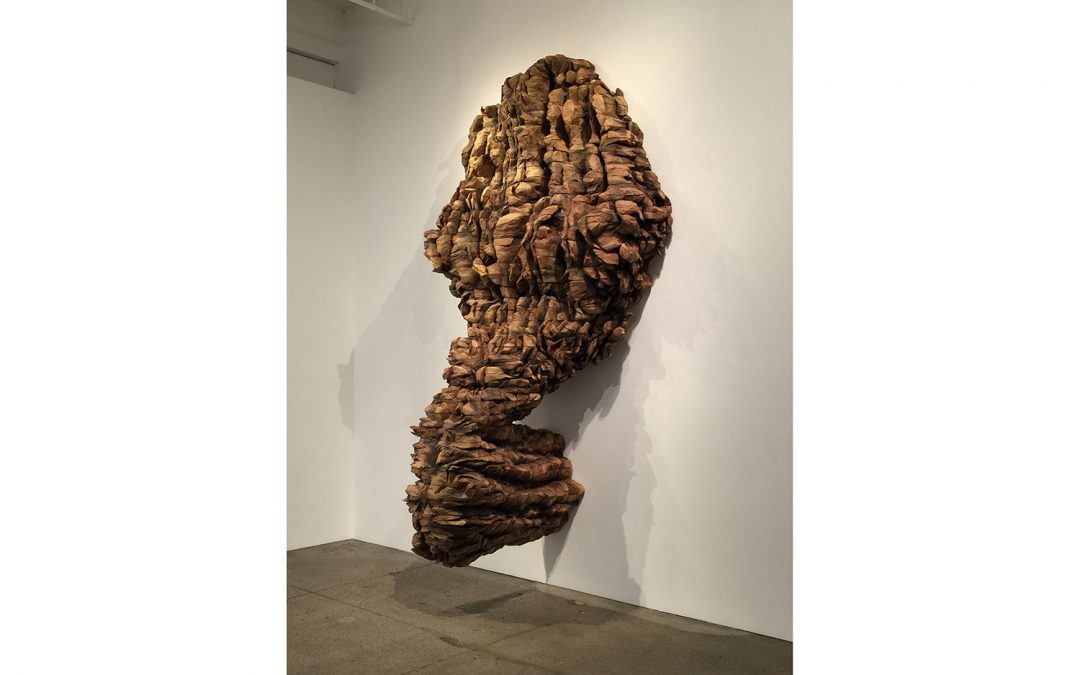

It happened again. Within seconds: scalp tingling, forearms in goose bumps, the held breath released and then tears. I am in a gallery seeing Ursula von Rydingsvard’s work on a beautiful summer day and I am suddenly engulfed by sensation. In spite of being in an entirely public place, in spite of my long familiarity with her work, I am overwhelmed by emotion

What is that moment of awe when we are swallowed whole by a form, a chord, a gesture, an image? What recognition? What liminal space do we enter from which we emerge altered, within our cells a new memory?

Where that gap opens for me, abstraction and paradox are always present in the work of art. Paradox is obvious: the co-occurrence of the unexpected that startles us from certainty. Abstraction, in its most challenging and restless impulse, articulates what there is at the edge of what we know. It seeks to meet what we have no words for yet. It can be deeply private and stunningly potent. In visual language, abstraction emerged as our familiar lexicon no longer held or comprehended our discoveries and actions, their trajectories and collateral damage. It grew as we became unfamiliar, even incomprehensible, to ourselves; as the center lost its hold and the untethering we now recognize in such abundance began to occur.

I am writing now to see into three artworks more deeply, to celebrate their richness, and to return eyes wide open to the gap into which I have fallen so many times but always by surprise.

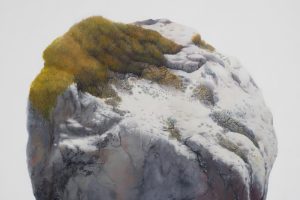

It is as though I am looking through a magnifying glass and a telescope at the same time. Exact in every way—the edges and textures specimen-like. The apparition is a boulder, a pebble, an asteroid, a nebula, a face, a dream image. The source of light is outside the picture plane to the upper right. The light is brilliant, illuminating the intricacies of the top surface. But it puts only the vertical surfaces in shadow; no shadow gives definition to the pure white space in which the three-dimensional form floats. It is a paradox of weight and weightlessness, of embodiment and disembodiment. I feel myself enter its space. I am not falling. I am held there in the absence of gravity, hovering, studying the magnificence of whorls of lichen and filaments of moss, and the reddening blush of love or catastrophe on its skin. There is just this moment—infinite and perfectly still.

.

It is not exactly a grid. There is one delineated horizontal that spans the width of the picture plane. From it, perfect vertical bands rise and fall in a mirrored sequence. The ascending ones surge upward strongly and continue in my mind past the top edge of the canvas. The descending bands dissolve at a nearly equivalent distance below, implying a second horizontal. The space is flat and deep simultaneously. There is an above and a below, a foreground and a distance. There are lines that seek and the one that holds—the shoreline. But the exactly parallel vertical bands and the absence of focus defy perspective. Without a source, the light is mysterious, menacing at moments, beckoning in others. This, the painting says, is the space you must navigate. My eyes travel the length, breadth, and depth; follow the flares of light; trace the eddies of darkness; and pause in the upper right corner where the thin pair of black lines, angled, short, and mismatched among the others, await.

Daniel John Gadd, I’ll Help You Swim (2018), oil, metal leaf, mirrored glass, wax string, oil paint on wooden panel, 40 by 33 by 2 inches

First, there is exuberance: the pure delight of color, untrammeled and entirely confident of its being. Mauve pink. Violet. Lavender. Iridescent gold and silver. Teal aqua. Specks of yellow. Black. Paint that is runny and stiff, brushed and poured. Swaths of color, an oculus, rays that reach forward and one that reaches backward. The form floats on the wall like a shield with magical powers, or a hero’s cape. It gazes back at me with such certainty, almost innocent, I think, of the largeness of its question. The string. I am drawn in. It dangles at the bottom of the construction, below the crisp edge of certainty, tangled. My eye follows it upwards as it follows the black that edges the gold eye and then dives into the mauve above. It is frayed, taught, slack, snarled—not just material. The string is memory. Stapled to the wood, it is a sutured tear, a hairline ridge of proud flesh. It is a line that is as tender as it is fierce. The tie that binds, the thread that holds, the rope that rescues. I pull back from the string to a middle ground, a place where I can take in the structure. Neither hidden nor exclamatory, the materials and construction have no want of illusion and declare themselves for what they are: builder’s chip board, broken glass painted and with edges as sharp as the wooden form is crisp, Philips head screws, oozed glue: pieces of something made into a triumphant whole.

“Why ask art into a life at all,” writes Jane Hirshfield in her collection of essays Ten Windows (Knopf, 2015), “if not to be transformed and enlarged by its presence and mysterious means. Some hunger for more is in us—more range, more depth, more feeling, more associative freedom, more beauty…. More prismatic grief and unstunted delight, more longing, more darkness. More saturation and permeability in knowing our own existence as also the existence of others. More capacity to be astonished.”

Perhaps it is a defining human instinct to create symbols where none seem to exist as the impulse to draw pictures from bright dots scattered in a night sky begat the knowledge that our place is a sphere and gave us the tool to navigate rather than wander in the diurnal blackness toward a destination. To have entered the liminal space that art opens is to arrive, rinsed and newly porous, on the other shore.

Millicent Young is an artist in Kingston, NY, and a frequent contributor to Vasari21.

Top: Ursula von Rydingsvard, DWA (2017), cedar. 104 by 70 by 51 inches

This is a wonderful essay. Thank you for articulating abstraction so well. For me it is inexplicable but you’ve filled the gap.

Marietta, Thank you. But I think perhaps the best I could offer is a small raft – really its unsayable and I agree with you. Jane Hirshfield’s Ten Windows is a beautiful remarkable set of essays. She’s as strong an essayist as she is a poet. Good to meet you here.

It strikes me that the feeling you are expressing of these three works is a visceral one. I feel it, too, and it is the strongest response I get to a piece of art.

Yes Barbara, it is definitely visceral and that is the signal that for me marks the potency of the work. It happens for me with other art forms – music, dance, writing….

What a wonderful essay. You are able to articulate the power of art so well.