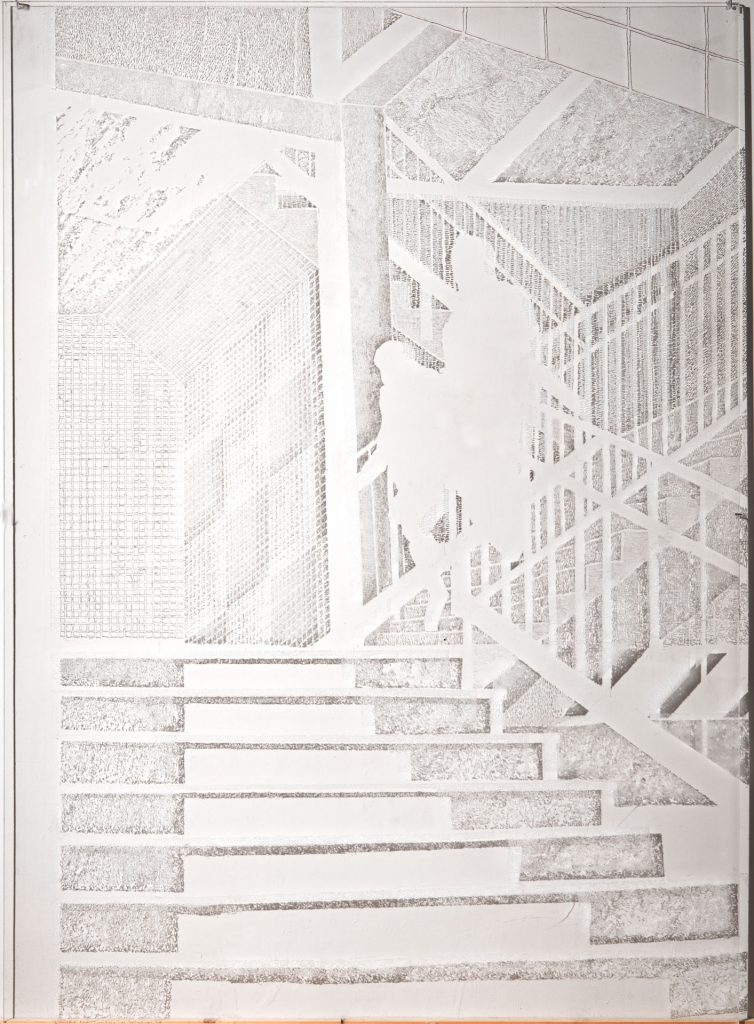

“My work is all about shadows and voids,” says William Norton, a tall, rangy, bearded man in his early 60s, whose seven-foot-high “drawings” on plexiglass panels were inspired by trips on the subway to and from his job at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “These are depictions of people not interacting, not communicating,” he continues. “I leave the figures as blank silhouettes, and if you walk up to one of the works, your shadow can pass into that space. So you can relate to the shapes on a physical level.”

The intricately chiseled, oversized images from the past couple of years also incorporate the tiles and the up-and-down maze of stairways familiar to users of New York City’s underground transit system. The stairs represent, he says, “the journey from heaven to hell.”

It’s a journey Norton knows well, having endured bitter custody battles for his son, wrangling with an ex-wife who became involved with a cult-like group of Mennonites, loss of a teaching job at Columbia University, and the torching of his loft. Oh, and the story includes an invaluable clue to his lost son’s whereabouts in the form of a teddy bear, a gift from artist Judy Pfaff.

But Norton’s artistic journey begins years earlier, when he was eight years old and living in Japan, where his father, an Air Force Pilot, was working with the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization. “Every time you turn around in Japan, everything is designed with aesthetics in mind,” he says. “I fell in love with the whole culture.”

Back in the States, after completing high school in Turkey, Norton entered the University of Texas in Austin, where at first he was determined not to study art because his dad did not approve. But in his second year he found himself drawn to the art department’s “irreverence” and “bunch of great teachers,” including one who taught the delicate skill of silverpoint, a proficiency that may still serve him well in incising fine lines on plexiglass.

And at college he met a girl. A tall blonde named Cynthia who looked a little like Farrah Fawcett from the 1970s TV show “Charlie’s Angels,” as he recalls from his first impressions. But she was a year ahead of him and would have nothing to do with him. He encountered her again, by accident, after moving to New York in 1976, where he was living in a loft on Chambers Street and making three-dimensional paintings, abstractions that included items picked up on the street.

The two eventually married, in 1985, and moved to Lyons Station, PA, where Cynthia soon became pregnant. Norton was teaching steel welding at Columbia by then, commuting to the city two days a week. But soon after his son’s birth, the artist’s wife began drifting away from him, becoming, in his words, “very demanding and very suspicious.” Before his son, Kit, was two, the couple had separated and Norton moved to Allentown, PA, where he was taking care of the toddler three days a week. One evening he returned home from his teaching gig to discover a protection-from-abuse order taped to his door. Cynthia was accusing the artist of sexually molesting their child.

A messy and protracted court battle ensued, and just as Norton was about to be awarded sole custody in 1990, his wife disappeared with Kit, abetted by an “underground railroad” run by her church group. The artist would not see Kit again for nearly a decade.

Norton moved back to New York, but was let go from his job at Columbia in 1993 because he no longer had an affiliation with a gallery and the department was looking to shore up its faculty with “name” artists like Pfaff, a long-time friend. Soon thereafter, he participated with Pfaff and other artists in a commission to build the immense indoor sculpture in the Philadelphia Convention Center.

A few years following the project’s completion, one of his co-workers got in touch to say that her aunt in Chicago had hired a woman from a local religious community to help with a political campaign. The woman claimed to be on the run from an abusive ex-husband and mentioned that when her son was born Pfaff had given them a teddy bear wrapped in her drawings and collages. Norton knew the woman had to be his ex-wife.

With the help of a dogged private detective, Norton tracked down Cynthia and his son in Goshen, IN, where she was arrested by the FBI for kidnapping across state lines. After yet another court battle, his son, then 14, agreed to come live with the artist in New York. There followed a brief halcyon period of about 18 months, when Kit attended courses at Cooper Union and the two seemed to be forging a close bond, but in another round of litigation, the prosecutor dropped charges against Cynthia. Swayed by his mother and her church, who threatened the boy with hellfire and damnation, Kit returned to his mother for good. “I came home one day and he had just packed up and left,” Norton remembers. And that was the last time he saw his son.

After his loft was gutted by fire in 1993, allegedly for the insurance, Norton did set design and illustration for movies and television to bring in an income. By 1996, though, he was back to painting, making figurative works on discarded hollow-core doors, from which he made the transition to plexiglass. “From using doors to thinking about the transparency of windows was not that big a leap,” he says. “It was a kind of Eureka! moment.”

From 2002 to 2005, he was director of installations at P.S. 1, overseeing a 14.5-million-dollar capital improvement program. And for the last four years, he has worked as an art handler at the Whitney–“just one of the guys that puts stuff on the walls,” as he describes the job.

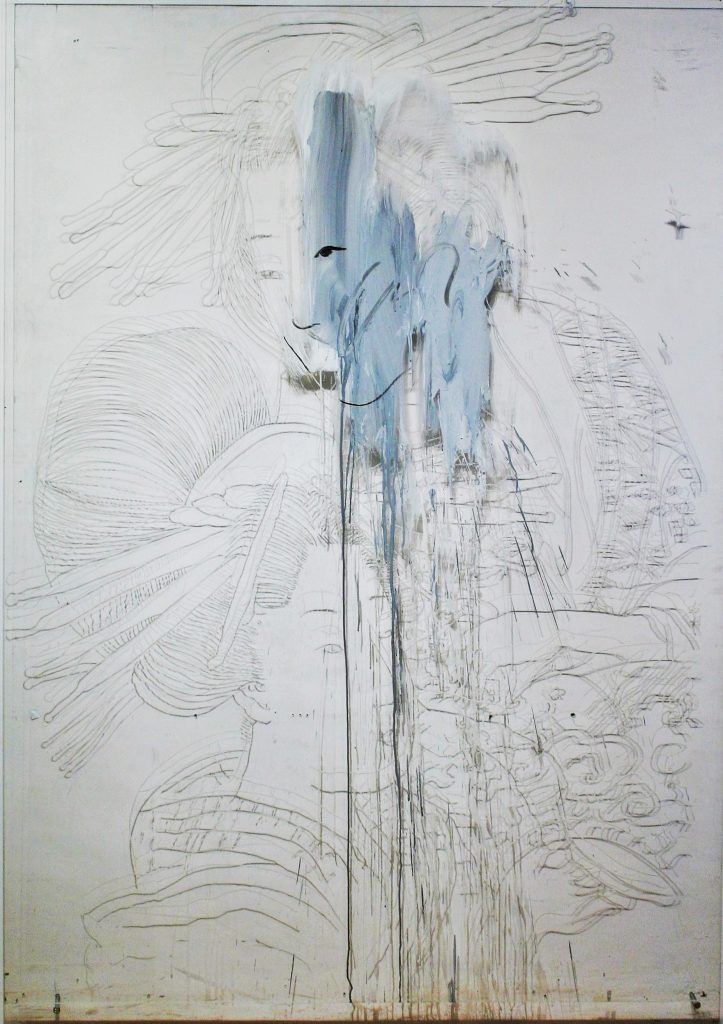

Since 1999, in spite of the tumultuous events in his private life, Norton has pulled together a fairly astonishing body of work on plexiglass. “To make the images, I take a dremel, basically a small drill or router, and I carve the lines into the plexiglass,” he explains. “When the light shines through, the shadows of the lines are cast upon the wall behind. For this reason, I suspend the plexi away from the wall surface. What you see are not the carved lines themselves but just their memory in shadow.”

In one way or another, his themes have also been inspired by memory, mostly recollections from his own childhood—geishas in Japan, photographs of aboriginal boys from National Geographic, and a comic-book superhero called Deadman. “Deadman was a ghost that kept coming back,” he says. And in his fierce desire to prevail, the character seems not all that dissimilar from Norton.

Now he believes he’s on the right track. “It’s been a rougher road than for many artists, but I’m the only one that can get the work done, and so I’ve got to keep going.”

Since 2015, William Norton (who prefers to be known simply as “Norton”) has curated eight exhibitions, primarily for art handlers, in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and has participated in 21 shows at galleries that include WhiteBox, Arthelix, Fishtank, and Jeffrey Leder. He lives in Bushwick, Brooklyn, with a rescue dog named Heihei (Mandarin for “black black”). “His attendance at all of the shows is mandatory,” the artist says. “His fan club comes to see him and check out what new scarf he’s wearing.”

Since 2015, William Norton (who prefers to be known simply as “Norton”) has curated eight exhibitions, primarily for art handlers, in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and has participated in 21 shows at galleries that include WhiteBox, Arthelix, Fishtank, and Jeffrey Leder. He lives in Bushwick, Brooklyn, with a rescue dog named Heihei (Mandarin for “black black”). “His attendance at all of the shows is mandatory,” the artist says. “His fan club comes to see him and check out what new scarf he’s wearing.”

Top photo: Norton with Heihei and Ghosts in the Machine (Winter), 2014.

fascinating read about a great artist…loved reading your writing, ann. now i understand norton’s art a lot better!

An amazing story and beautiful artwork, too. Thanks Ann.

…a little late reading this but love Norton’s dogged determination despite what shadows he needed to pass through throughout his life…find his work endlessly fascinating as it exits in a nether world between substance and shadow, always demading close detailed scrutiny as its imagery and subtle shadows cast a magical narrative.