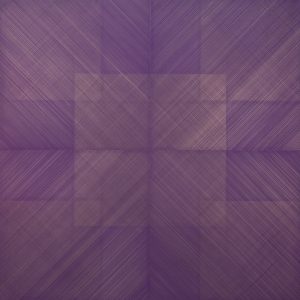

Susan Schwalb, Poetry of the Square III (2018), silver/gold/copperpoint, and purple gesso on wood panel, 24 by 24 by 2 inches

Far from disappearing from an artist’s regular practice, as many critics have complained, the possibilities for drawing have only expanded in the last century, limited only by the imaginations of their creators. Picasso made drawings with a small electric light in a darkened room. Calder’s Circus can be seen as an assemblage of three-dimensional drawings made with wire. Andy Goldsworthy’s “Rain Shadows,” in which the artist uses his whole body to create an impression on the ground, could qualify as a way of drawing still using that most primitive pigment–wet dirt..

As the survey below reveals, artists still turn to drawing in traditional media—as studies for sculpture or paintings, as a way of unwinding, as plein-air exercises, or just to sharpen one’s skills in seeing. And the medium remains as malleable as ever: Jill Bedgood’s “Rocker and Cradle” series, at the top of this post, are made from sawdust sifted on to wood templates. Are these truly drawings? I don’t see why not.

Susan Schwalb: “My primary medium for over 40 years has been the Renaissance technique of silverpoint and metalpoint drawing. Juxtaposing a wide variety of metals (silver, gold, brass, copper, platinum, pewter, bronze and aluminum), I obtain soft shifts of tone and color. Horizontal lines evoke an atmosphere of serenity, and the shimmer of light on the surface, created by the metals, is quite unlike any of the usual effects.

“I have been working within a square format almost exclusively since 1997. An even grid of narrow horizontal or diagonal lines forms the basic structure and serves as a spatial context for irregular events on the surface. My paintings and drawings are always done in series and each work is generally inspired by the piece or pieces created before it.”

Tracey Adams: “My love of paper began at age three when my father gave me a colorful bundle of origami paper. Sixty years later I’m still in love with Japanese paper, though the processes have evolved from drawing with wax crayons to woodblock printing to different combinations of media, each with its unique qualities.

Rachel Wolfson Smith, The Cabin, detail from a 54″ x 110 drawing, 54 by 110 inches, graphite and pigment on paper

“Drawing has been a part of my daily practice for almost 30 years. It allows me to improvise and experiment with different media, especially when I’m working on more precise work. I usually draw in the evenings when there are few distractions. I title most of my drawings with the day and order they’re created. This one is 0118.1.”

Rachel Wolfson Smith: “I love drawing for its limitations—my marks cannot be completely concealed. The structural lines and notes I make as I build my drawings remain for the viewer to dissect. The scale is often huge (up to 20 feet), and the use of such a small tool on that scale makes them read very differently close up and far away. Through composition, landscape, vehicles, and most recently text, my drawings resonate on an emotional level that people say can be ‘felt.’ I’m currently pushing though what I have known graphite’s limitations to be.”

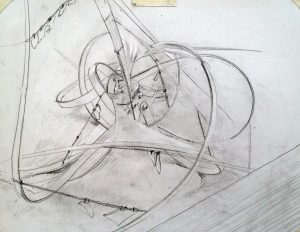

Jamie Hamilton’s show, “Active Measures,” is at the Torrance Art Museum in the South Bay region of Los Angeles through May 18. The drawing shown here gives an index to the complexity of his sculptures, which are made from raw surplus materials such as magnets, aluminum from the aerospace industry and dichroic glass from optical laboratories. Says the museum’s website: “The artist has made biological-mechanical objects that conjure wondrous and terrifying aspects of our post-human condition. Contrast of scale, recursivity and reflection introduce great complexity into precise forms, confusing and dazzling the viewer.”

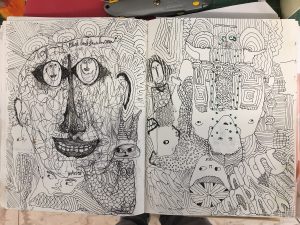

Karen Jelenfy: “I spend my evenings drawing. Drawing with a pencil is how I think. The small drawings keep me limber and active. The larger drawings often lead to paintings, although the end result may not look like the original drawing at all. They are a kind of calisthenics. My whole body is engaged, as it is when I paint. So drawing mainly functions as a way to keep my hands and my body in motion. I am a lazy creature! The drawings propel me off the couch and up to the canvas!”

Judy Sigunick: “Drawing helps me to see through a part of my brain which isn’t fully accessed in other ways. My sketches are oftentimes opening portals for who knows what—without them, I’m jumping into icy water and although an impulsive attack with paint or clay has sometimes produced meaningful and unexpected work, mostly I’d rather not.

Debra Claffey, Indigo Ice #4 (2018), oil and trace monotype, encaustic, graphite on paper on panel, 36 by 36 inches

Debra Claffey: “I do many, many drawings and best enjoy doing trace monotypes, which involves drawing on the reverse of a sheet of paper, picking up the impression from a layer of paint. It creates a particular and nuanced quality of line I have found in no other way. I often layer these monotypes on to a panel. The title is from the color. Indigo is a plant-based hue and using it in all its complexity sometimes makes me think of frozen foliage. I’m inspired by plants and the forms and contours of foliage. I spend a lot of time as a professional gardener contemplating the intelligence and the adaptability of plants and how little we respect their contribution to our ability to live and breathe on this planet.

Lily Prince: “My favorite thing to do is plein air drawing, returning repeatedly to a place of particular interest and beauty. I start by doing a few black and white oil pastel drawings and then move to color. This is from summer 2017, when I was living for the month of August high up above Lake Como, Italy, drawing every day.

Jill Bedgood: In 2008, artist and collector Damian Priour sent miniature chairs that he created to 100 colleagues, contained in an eight-inch box. If the artist chose to keep the chair, the artist had to make her own chair, sized to fit the box, and return it for inclusion in the exhibition “The Texas Chair Project” at the Austin Museum of Art. I sent a bag of sawdust with instructions for Eternal Vacation.

On the final day of my sister’s treatment for cancer, a friend of hers arrived with two handmade Adirondack chairs. She was thrilled to receive these, and immediately instructed me to place them in the backyard so we could sit together and look at the beautiful mountains and sky of Utah. The following day I had to leave. That was our last time together.

When I installed my work at Damian’s home, we talked at length about the experience that initiated Eternal Vacation.Unbeknownst to me, he was also dealing with the same illness. After his passing, Damian’s stone and glass chair became more personally significant. About a year later, it seemed appropriate for me to give the chair to a family member, to pass it on to provide a sense of healing.

The sawdust chairs are the dimensions of actual chairs. Chairs are drawn on paper; then balsa wood is cut in the shapes of the negative space and pinned together. The wood templates are placed on the floor, sawdust is sifted into the open areas, the template is carefully removed, and the image is tidied. As the viewer walks through the sawdust, it is displaced and distorted, and nature takes its course. The sawdust is swept up and removed at the end of the exhibition, similar to Tibetan Buddhist sand paintings that reference the “transitory nature” of the physical life.

“An Adirondack chair implies the ultimate peaceful vacation,” I wrote in my artist statement for the project. “The back of the chair confronts the viewer, positioned looking away. The sawdust, similar to sand paintings, is impermanent, moves, is swept up and discarded–the eternal journey.”

Kevin Cannon’s leather sculptures have been described “mordantly witty monuments-in-miniature.” Their eccentric shapes, painted in earthy colors, recall Arp, Brancusi, primitive fertility figures, and even perverse children’s toys. But his drawings are something else, often capturing the ephemeral nature of landscape and shifting light around his hometown of Taos, NM, where he lives in the same adobe building once owned by D.H. Lawrence and occasionally occupied by Georgia O’Keeffe, Willa Cather, and Dennis Hopper. “Drawing,” he says, “figures out what you’re doing for you and takes you to places that you wouldn’t get to otherwise.”

And finally, two who still pursue the time-honored practice of drawing from the model in the sort of life-model classes that have been around since the 16th century. “I use figure drawing to hone my skills in seeing—and I use occasional figures in my paintings—and I love to draw. Which is why I was a printmaking major in college,” says Barbara Kemp Cowlin.

Though her “formal” output is strictly in abstraction, Peggy Klineman says, “I love to draw the figure. Studying a body helps me see shapes and subtleties, and I particularly like drawing with charcoal because of its plasticity. I put down lines and wipe them off until I capture the desired shapes and shading, so that even though these are still drawings, my approach remains very painterly.”

Top: Jill Bedgood’s sawdust “Rocker Cradle” drawings, 2008-09

Wonderful and fascinating compilation. Thank you for including my work!

The different approaches brought together here make me want to draw more and to experiment. Thank you.