Traditionally summer is the time when you tackle those big door-stoppers you skimmed in college: War and Peace, The Magic Mountain, Middlemarch. Or you turn to thrillers and mysteries, escapist fiction that doesn’t tax the brain too much and is as digestible (and about as memorable) as watermelon. Not me. I like books I can absorb in one sitting, barely breaking a sweat. What I’ve seen of books about artists lately—the recent bio of Elaine de Kooning, for example—has been none too inspiring, and so I unearthed a couple I wanted to revisit and one smashing new novel.

James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait, by James Lord (originally published by Doubleday in 1965, available on Amazon, at used book stores, or possibly in your local library)

In the early 1960s, an intrepid young American writer named James Lord bravely accepted Alberto Giacometti’s invitation to sit for a portrait by the maestro, who was by then an international celebrity almost on a par with Picasso. What was to be an afternoon’s exercise, “a quick portrait sketch on canvas” in Lord’s words, turned into 18 days of posing as Giacometti wrestled with self-doubt, despair, and an “aura of anxiety that surrounded our mutual work in progress.” Lord’s account includes the substance of many of their conversations—Giacometti’s reminiscences about escaping war-torn Paris, his asides about art and artists (especially Cézanne and a certain portrait by Jan van Eyck), and the occasionally deadpan exchanges between them. Example:

“Later, he said, ‘You look like an Egyptian sculpture, but more handsome.’

“’Why more handsome?’ I asked. ‘Because I’m alive?’

“No. Simply because you’re not an Egyptian sculpture, that’s all.’”

Lord surreptitiously took careful notes about the more than two weeks he spent posing and made photos of the work in progress, noting the “identification between the model and the artist, via the painting, which gradually seems to become an independent, autonomous entity served by them both, each in his own way and, oddly enough, equally.” Giacometti’s exasperation with his progress, his inability ever to get it right to his satisfaction, does verge on the comic at times, but it’s in no way close to the buffoonish, senescent character played by Geoffrey Rush in the recent movie “Final Portrait.”

Any artist who has ever struggled with doubts about the worth of his or her work—and who has not?—will find solace in Lord’s deft account, written more than 60 years ago and still as vivid as an encounter with one of his skeletal sculptures on the ramp of the Guggenheim (that show’s up till September 12; read the book first for a better sense of the engaging but tormented genius behind it all).

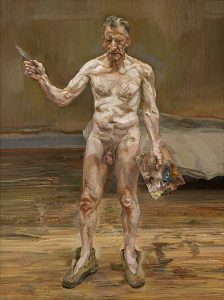

Lucian Freud: Eyes Wide Open, by Phoebe Hoban (New Harvest, 2014 available on Amazon and through used bookstores; also, of course, check the library)

Lucian Freud was another who grappled with demons, so much so that he abandoned an early, exquisitely linear style—mostly portraits—for a more painterly and clotted approach that made him rich and famous in the mid-1950s. His was an unsparing kind of realism that is more aptly described not as “warts and all” but as “warts and more,” and he painted everyone from Kate Moss to the Queen to a maverick gay performer named Leigh Bowery. As one critic noted, “the act of painting was his one opening to something like empathy, a fact best exemplified by his portraits of his mother—made after what he called “a lifetime of avoiding her”—in her decline in the 1970s, and some of the depictions of his innumerable daughters.“

Written a few years after her subject’s death, Phoebe Hoban’s compact, lively, and incisive life of Freud pieces together a full biography in 160 pages. The painter spent long and punishing hours in the studio, but managed nonetheless to hobnob with high society (even marrying into minor aristocracy), maintain relationships with numerous lovers (he fathered 14 children by multiple partners), and remain dedicated to a brand of unfashionable realism at a time of rapid revolutions in painting. For all his carelessness in matters of the heart and his unsparing geographies of the flesh, Freud comes across as a lovable and entertaining rascal. One only wishes there were a few more reproductions of the paintings—this is best read with the Internet within easy reach.

Self-Portrait with Boy, by Rachel Lyon (Scribner, 2018)

An ambitious young photographer, living in near-squalor in a DUMBO loft in 1991, just happens to catch a neighbor’s young son as he falls to his death outside her window. Lu Rile knows it is the sort of image that can launch a career (provided you sustain disbelief long enough to accept that one photo is capable of such a thing) but must struggle with three menial jobs, an ailing father, a skeptical dealer, and her budding friendship bordering on infatuation with the boy’s grief-crazed mother.

Lyon’s remarkable debut novel Is part ghost story, part romance, and as one reviewer put it, “an unforgettable portrait of a true art monster—a young woman hell-bent on pursuing greatness, no matter the cost.” What sets the book apart from other novels that attempt to portray the art world of any era is Lyon’s refusal to indulge in the usual stereotypes by creating sharply etched characters in crackling, charged language. She also gets the nascent real-estate boom closing in on an artists’ enclave, and the fear and greed urban development can unleash in a fragile community.

And, of course, the ruthless ferocity of many young artists, for whom every event, no matter how grotesque, is a potential subject. Consider her description of Lu’s finding a nest of rats in her loft:

“They were babies, each not even the size of my fist, pink with sightless eyes and squirming feet. They were curled together in a pile of rags and torn photo paper and shredded cardboard. The mother was squeaking shrilly, concealed somewhere behind me. I rose up again and left the darkroom to retrieve my Rolleiflex. I came back in and squatted down and focused in on their tiny groping hands and open mouths. The mother was going out of her mind, squeaking wildly as if she were a much larger beast, hunkered down and ready to attack. I took a picture, then got up and left her to her brood.”

Self-Portrait with Boy is so ably constructed, so memorable and haunting, that I closed its covers for the first time and then read it all over again.

Ann Landi

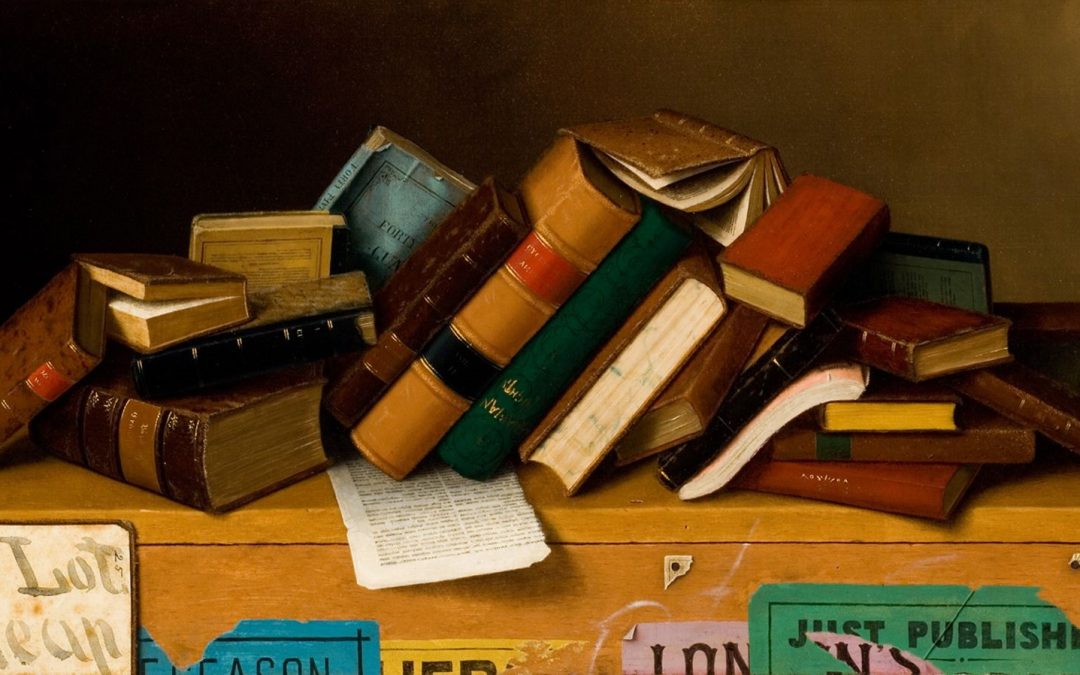

Top: William Michael Harnett, Job Lot Cheap (1878), oil on canvas, 18 by 36 inches, Reynolda House Museum of American Art