When painter Leslie Parke was a small child, she would head downstairs early in the morning and open one of her parents’ art books, squatting on the floor and pressing her face into the color reproductions of Fifty Centuries of Art. Her goal was not so much to study the paintings as to live inside them. “Here in tiny landscapes behind Rogier van der Weyden’s Madonna and in the curtained Dutch rooms of Vermeer, worlds opened up to me that were at once more vivid and appealing than the one I lived in,” she later wrote. Like Alice in Through the Looking Glass, she longed to be on the other side. “I wanted to live inside a painting,” she recalls.

Many years later, all grown up and an artist herself, Parke moved into a ramshackle apartment above the old Grange Hall in Shushan, a small town in upstate New York. With her landlords’ tacit consent, she undertook some serious renovations, tearing down plaster walls, rewiring, and putting up sheetrock. When she reached the bedroom, whose walls had long since dulled, she had a different idea about upgrading, one inspired by those encounters with paintings years earlier.

It was 1998, and Parke had just returned from the large enchanting retrospective of the works of Pierre Bonnard at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “I decided that instead of tearing down the walls, I could use the walls any way I wanted,” she realized. “And what I wanted was to cover my walls with Bonnard’s paintings.” So she painted his windows, copied from the catalogue, above the bed and on an adjacent wall. A corner of his room became a corner of her room. She added glimpses of the landscape Bonnard would have seen outside the windows of his house in Vernnonet, a small village not far from Monet’s house and gardens in Giverny, where Parke had stayed as an artist in residence. And then came further additions: “My room expanded as I extended his floor onto my walls, adding a painted balcony, a fireplace, tiled floors, an iron bathtub, a dog I called Flat and two unnamed cats,” she says. “I painted plants, chairs, tables, stools, and still lifes, everything but the figure. I wanted to be the figure in the painting.”

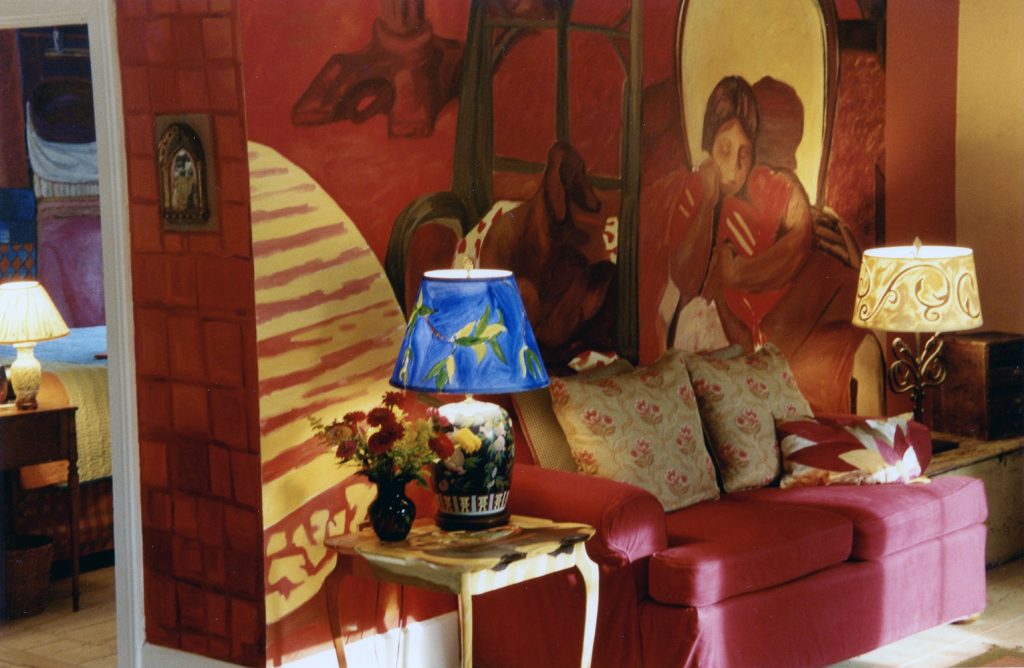

When Parke had finished with the bedroom, she moved on to other areas of her apartment. In the living room, she added a Bonnard picture of a balcony. Behind the couch, she painted a young woman in an armchair, her chin resting on her hand; next to her is one of Bonnard’s friendly dogs. By now the artist had decided she didn’t need to be the sole occupant of this re-invented world, and in the entryway to the bathroom included a cut-off, legs-only view of one of the master’s nudes in a tub (his wife, Marthe, whom he painted obsessively for decades, was the original model). In the dining room appeared a huge still life of grapes and rolls against a lacy tablecloth. (This replaced an earlier mural of Marthe and Renée, Bonnard’s mistress, who committed suicide. “That seemed really bad karma, so I changed it,” she says.)

And then came additional accoutrements. Parke painted over what furniture she had acquired or inherited from her parents. On a dresser she outlined cadmium yellow wall tiles that shade into lavender. She decided her pale floral rugs looked “sickly” in the bedroom. “So I took up rug hooking and hooked Flat into the tiled floor.” She painted over lamps, as well, and started searching out bed linens and additional rugs that looked like they belonged. She found a wind-up 1910 clock, reminiscent of Bonnard’s era, and bought a round table to go with the mural in the dining room. During a residency at Vallauris in Provence, where Picasso once had a ceramics studio, she made plates embellished with more Bonnard figures and motifs.

The entire “Bonnardification” of her living quarters was spread over about a 10-year period, so that she still had time to pursue her own career. “One Sunday, as I stood on my ladder, painting yet another window on the wall, I saw the Bonnard catalogue, open on the floor in a square of light,” she recalls. “I was living in a painting. I sat in the painting, moved in the painting, and slept in the painting. My real and imagined worlds merged.”

Leslie Parke is a recipient of the Esther and Adolph Gottlieb Grant for Individual Support, the Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest grant as artist- in-residence at the Claude Monet Foundation in Giverny, France, and the George Sugarman Foundation Grant, among others. She has showed her work at the Williams College Museum of Art; the Bennington Museum (Bennington, VT), the Museum of the Southwest (Midland, TX), the Fernbank Museum (Atlanta, GA); the Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Museo de Arte Moderno, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Parke has a BA and MA from Bennington College. Her work is in numerous corporate and private collections. More about her can be found at leslieparke.com.

Image credits: All photos of Parke’s apartment are by Duane Michals; photo of Leslie Parke by Andrew Ciccarelli

Brilliant.

This is amazing!!

So YOU, Leslie! Wonder-full.

Wonderful! How inspiring.