What can it really do?

While driving home from Albuquerque on Thursday, terrified and disgusted by the news on the radio, I popped in a CD from an audiobook that had been languishing in my back seat for weeks. Picasso’s War, by Oliver Wyman, tells the story of the artist’s colossal masterpiece Guernica, from the destruction of the Basque village in northern Spain by fascist forces under General Francisco Franco in April of 1937 through the controversies that haunted the work for decades. It’s a gripping story (so far), and the painting is still a powerful and stirring indictment of the atrocities of war, rendered in Picasso’s heavily symbolic, almost cartoonishly fractured language. I saw it as a kid, when the canvas was at the Museum of Modern Art (it now resides at the Reina Sofia in Madrid), and still remember being gobsmacked by its size and anguished iconography.

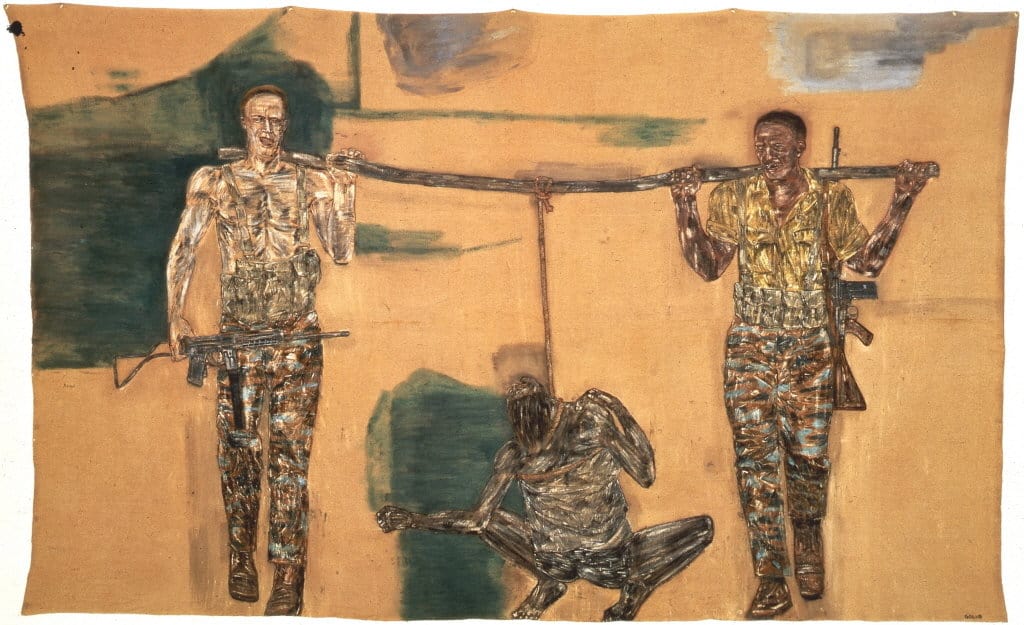

Thinking about Guernica led me to ransack my mental inventory for other images of politically charged protest art. So many great artists have turned their talents to chronicling horror and injustice down through the years that examples often hold pride of place in museum collections. The best, like Goya’s Third of May 1808 and his series of etchings “The Disasters of War,” are visual records, reconstructed or re-imaged, of the awful toll paid during times of conflict. Others, such as the series or paintings Manet made of the execution of the puppet-emperor Maximilian, bring to vivid life the political bungling of the powers-that-were. Closer to our own times, Leon Golub responded to the war in Vietnam with huge, edgy, expressionist tableaux of torture and combat.

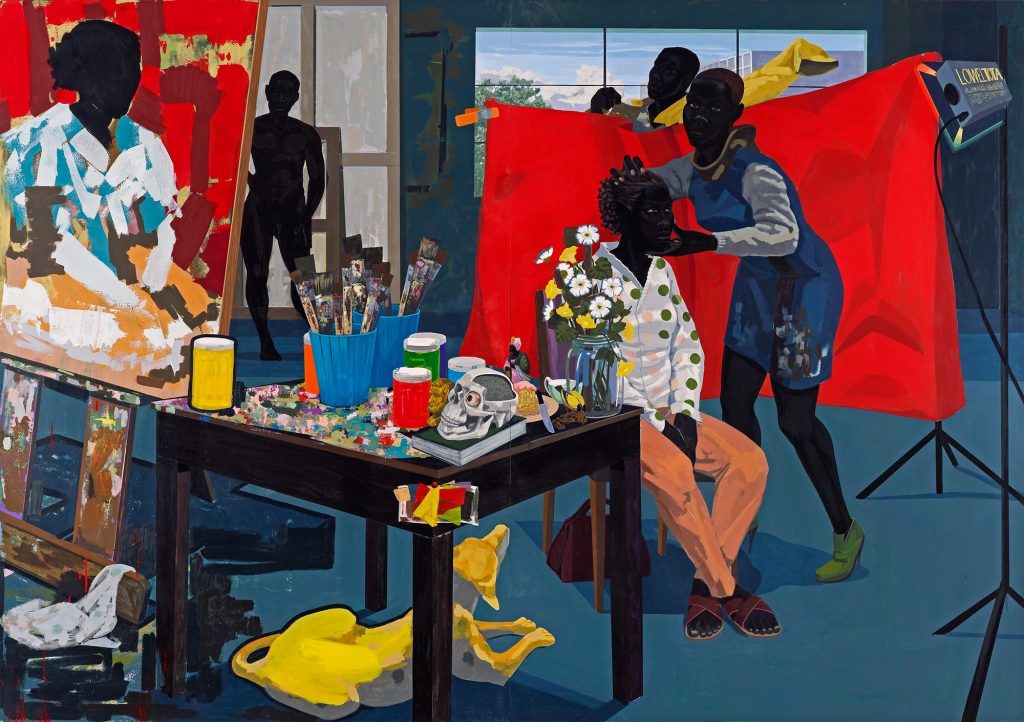

As for social protest—art that condemns abuses of power and conditions of all kinds—every era has its painters, photographers, visual satirists, and even video and performance artists who take as their subjects the appalling inequities around the globe. To cite just a small handful of recent examples, Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall focus on the ongoing problem of racism; Banksy takes to the streets with subversive epigrams and graffiti; and Ai Weiwei has made Chinese government corruption and cover-ups the focus of all his recent endeavors.

Already the Trump administration is inspiring its own brand of protests among artists, perhaps beginning with Deborah Kass’s indelible portrait of the snarling president-to-be during the election season. Shepherd Fairey has a new line of posters featuring portraits of marginalized people (the image of a Muslim woman wearing an American flag as a head scarf was on prominent display during last week’s women’s march). Richard Prince returned the $36,000 fee for a portrait of Ivanka Trump (why was he painting her in the first place?). And Christo just announced that he would not build “Over the River,” a vast public artwork consisting of a silvery canopy above 42 miles of the Arkansas River “because the terrain, federally owned, has a landlord he refuses to have anything to do with: President Trump,” according to the New York Times.

These are all noble and stirring gestures, generally so visually appealing that they rouse the senses on some level. But how often do they have any real effect on our sentiments or our inclination to take action—to hit the streets, stage a sit-in, call our representatives, write letters, or perhaps quit our jobs and leave the country? If you’re not already converted, you probably will not change your mind because of an artist’s agenda, no matter how powerfully presented.

I would argue that political or protest art is wonderful to behold but does very little to nudge public opinion, and often results only in the persecution of the artist. (Of all those cited, Ai’s art, which includes blogging and other internet activism, has probably had the most impact, but for his attempts to expose the rot at the core of Chinese politics, he has been imprisoned, forbidden to leave the country, and seen his studio demolished overnight.)

The late Robert Hughes argued that so-called “fine art” does not really have the power to sway beliefs and attitudes. “What really changes political opinion is events, argument, press photographs, and TV,” he observed in one of his characteristically tart essays. And when I think back to documentary photography in particular—Nick Ut’s shot of a screaming napalmed Vietnamese girl, the images that emerged from the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib—I’m inclined to agree. If those, and the dogged reporting that accompanied them, didn’t affect your opinion of two very lunatic wars, then you are made of stone.

Which leaves me wondering what images might finally unite more people against this administration, assuming photography still has the powers it once did. Parents torn from their children to be deported? Women who die because the government cut off its aid to third-world clinics? Peaceful protesters clubbed by police?

I hope I never have to see them.

Top: Leon Golub, Mercenaries, 1976

Superb Ann.

Nice piece Ann! And I think you’re right..

A very powerful and thoughtful article. I think you’re right, too.

A stirring and insightful piece.

I think I agree. And that also saddens me. It also saddens me that a life – mine- lived consciously and kindly has not made enough of a difference.

But the point you make about the role of photojournalism is well taken and one I’m really interested in – you might be interested in reading (in your spare time!!!) from Ed Kashi’s blog about art photography versus photojournalism.

Anyway, thanks for another great op-ed

Dear Ann,

Please in relation to your thoughtful essay check out the Artist Poster Site established by Taos Artist Hank Brusselback

‘POSTER THE WALLS.COM’

We must continue to RESIST

Most Importantly we must encourage people to use their VOTES in these upcoming midterm elections.

As Artists it is our responsibility to speak Loudly thru our talents!!!!

SILENCE IS COMPLICITY AT THIS MOMENT

Sincerely,

Stephen Parlato