A brief memoir of catering, art-history classes, and friendship

For part of my junior year in college I lived off campus with one of my best friends, Kate, a woman thirteen years older than myself, and in many ways a kind of big-sister to me (since I had none). Kate was a late bloomer, a graduate student in the English department, whose big passions were for Shakespeare and John Donne. She was an oddity, both in the department and at Princeton, for being older than the other students and a far different kind of acolyte than was the norm in the staid male-dominated ranks of aspiring English professors. A generously endowed woman with a flashing smile and a bawdy sense of humor, Kate often drew stares and occasionally comparisons with Sophia Loren, a resemblance that usually annoyed her. Serious students of Shakespeare were not supposed to look like Italian movie stars.

Her background was unusual too. She grew up poor, on the outskirts of Detroit, the daughter of devout immigrant parents. After acquiring a bachelor’s degree at a small, all-women’s Catholic college, she worked for several years at administrative jobs in Washington, D.C., before determining to get a Ph.D. and go into college teaching. She somehow landed a prestigious fellowship and admission to Princeton, an improbable long shot for her age and upbringing.

The house we lived in was a few blocks from campus, the top apartment of a ramshackle building that would be ripe for gentrification a couple of decades later. But not then. I slept on a lumpy sofa-bed in a narrow spare room, Kate occupied the one real bedroom and slept with her cats, Riesling and Scudamore, when she was not sleeping with a senior member of the department who was a scholar of Edmund Spenser (later he would break her heart by marrying a ballerina; still later he would come out of the closet, perhaps an appropriate move for an expert in The Faerie Queen).

Kate loved to cook and eat, but was constantly dieting. I would sometimes awaken at two or three a.m. to the pungent aroma of sauerkraut, a favorite from her childhood and a snack with almost no calories. She would be curled up in the living room on her third reading of Troilus and Cressida, or somesuch, forking shreds of the stuff into her mouth, oblivious to everything else.

Where we got the idea to launch a catering business I don’t know or remember. But we both needed spare cash, and Princeton in those days had no real catering establishments. (It was by no means a seedy town, but it would have to wait a few years for a yuppie clientele that would demand such services). We decided, of course, to start with faculty dinners and parties and distributed flyers all over campus.

Our first customer was the head of the philosophy department, a dignified and genial old widower who owed many return invitations to other faculty members but didn’t know how to cook. We offered a menu with a choice of main courses, old ‘60s standards like duck à l’orange and boeuf bouguignon. He went for the beef. And though Kate was by far the more expert cook, I was delegated to do the honors, aided by Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking (from which I’d successfully made soupe a l’oignon and crème bavarois a couple of years earlier, when I went on a serious culinary kick in my parents’ Upper West Side kitchen).

“I somehow messed up, possibly by using cheap burgundy. The end result was dishwater gray, not the hearty deep-russet of a good bourguignon.”

I followed the instructions to the letter, but somehow messed up, possibly by using the cheapest burgundy I could find. The end result was a dreary dishwater gray, not the hearty deep-russet of a good bourguignon. I added a few drops of red food coloring. And then the whole bottle. I added about a half-cup of ketchup. The color was still all wrong. I raced out to the little grocery store on Nassau Street and bought more food coloring, and at some point between the possibly noxious dye and the ketchup, the color gradually turned palatable. And the stew tasted pretty damn good! (I still add a little ketchup whenever I make this dish. Forgive me, foodie purists.)

Soon word got around about the peppy student caterers and we were booked for other dinners, cocktail parties, even a wedding. Kate was brilliant with the fussy but still popular old stand-bys, like salmon mousse in aspic or beef Wellington. I recall making insane numbers of mushroom turnovers, cucumber sandwiches, cheese straws, quiche Lorraine, and rumaki. The New York Times Cookbook was our bible, and I still consult it now and then, though so many of the recipes are out of fashion.

“We set the frozen bird in the bathtub to defrost. The next morning, we discovered the cat blissfully licking the skin.”

Of course there were other near-disasters. One customer wanted a large turkey for a dinner or cocktail party. There were no fresh turkeys that time of year, and so we set the frozen bird in the bathtub to defrost. The next morning, we discovered the cat blissfully licking the skin. So we added a new dish to our repertoire, Riesling-basted turkey. Riesling also ate about a quarter of the second layer of a wedding cake, a gâteau genoise, which Kate had left out on the dining-room table with a “sealer” coat of frosting. Fortunately, she had baked an extra layer and was able to patch up the damage.

And I still had school in between catering gigs. I was an art-history major, taking a couple more required courses toward graduation. One was a survey of Greek sculpture, taught in the conventional way: look at the slides, listen to the professor (a lovely older woman who had written several books on the subject), read the required texts, and get the images and information right for the exams.

“She was a forbidding figure—handsome in an angular way but deep into realms of abstruse thought, which we tried dutifully to understand in her lectures and in the pages of Artforum.”

The other was a course in contemporary art, taught by then-rising formalist critic Rosalind Krauss, a disciple of Clement Greenberg who would later accuse him of mishandling David Smith’s estate. Krauss had very decided views about what was worthy of our attention. In one tour around the campus—which boasted some very fine examples of mid-century sculpture, including works by Picasso, Henry Moore, and Tony Smith—she could hardly hide her disdain for, say, George Rickey. In the classroom, she toyed with an unlit Marlboro while veering off into digressions about Wittgenstein or Bataille or Lacan. Even the graduate students in the class seemed utterly lost. Though scarcely out of her 20s, she was a forbidding figure—handsome in an angular way but deep into realms of abstruse thought, which we tried dutifully to understand in her lectures and in the pages of Artforum, where she was then an associate editor.

This was possibly the most schizophrenic time in my undergraduate career, between slopping around in our small kitchen, serving and clearing meals, putting in my time at the library, and writing papers. I lost ten pounds from dining on leftovers I never wanted to see let alone taste again, and worried about Kate’s erratic romantic life, especially after she came home crying late at night.

At the end of the semester, Krauss gave me a B in her course. I was indignant. The lowest grade I’d ever received in art history was an A-minus. I thought I’d written a pretty nifty paper drawing some parallels between Marcel Duchamp and Bruce Nauman, but I was too terrified to dispute the grade, to confront her in person, to figure out what I was doing wrong. I did, however, make enough money from catering so that I would not have to work that summer and could concentrate on a senior thesis about Kenneth Noland. (How I squeezed 100 pages out of that is beyond me….lots of footnotes, most likely. An art historian of a different stripe, Sam Hunter, gave me an A on it.)

In the fall Kate went off to Washington, D.C., on a fellowship to finish her dissertation, and continued with the catering adventures on the side. But the closeness we’d shared as roommates and harried cooks began to fade. We saw each other on and off in the following years. Once, when I was in grad school at Columbia, she visited a few months after breast-reduction surgery (eleven pounds removed!), and in typical Kate fashion drew her sweater over her head to show off the bra-less results. A couple of years later she came to New York and met my future husband. By then, she was dropping allusions to becoming a lesbian and made no secret of her distaste for both him and the institution of marriage.

That was virtually the end of the friendship.

And then, about six years ago, while still living in New York, I got an email telling me Kate had died of liver cancer. I knew she had been teaching at the University of Texas in Austin, but did not realize her entire career had been spent there. The friend praised her for bringing a better understanding of Shakespeare to so many, and I wondered how she had found me. Did Kate leave a list of “loved ones”? How did she get my email address? I was saddened then that we’d fallen out of touch but flattered that I still had a place in her heart. The friend in Austin said she was putting together a memorial and a book of remembrances. Did I want to contribute?

I scarcely needed to think about that one. I wrote back: “Kate was an extraordinary friend and mentor at a formative stage in my life. She was also a resourceful and inventive cook. Her recipe for Riesling-basted turkey is still a highly sought-after but closely guarded secret.”

Ann Landi

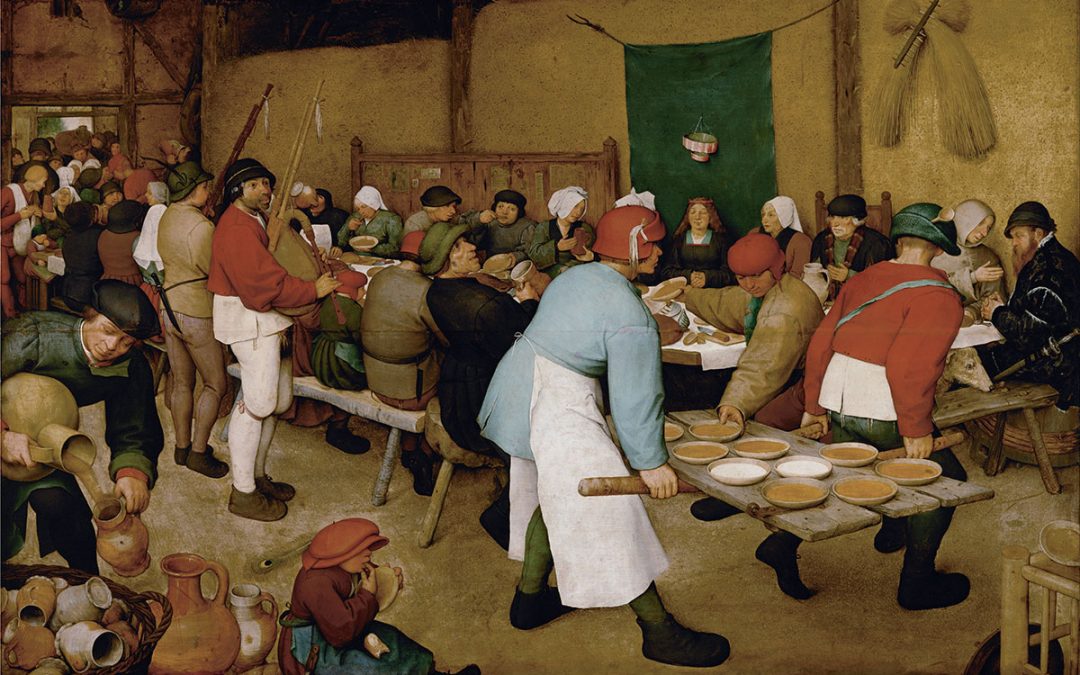

Top: Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Peasant Wedding (ca. 1568), oil on panel, 45 by 65 inches.

Love this story of roommates and friendships Ann!

A wonderful memoir!