More Tales of Accidental Discovery and Enlightenment

Legend has it that the great early 20th-century painter Wassily Kandinsky discovered abstraction when he left one of his landscapes positioned upside-down in his studio. He returned the next day and loved the almost non-objective whirl of shapes and colors, which became a point of embarkation for a wholly new style. (I have not been able to verify this story, but it’s certainly a fine tale.) Closer to our own times, in the summer of 1961, a student brought sculptor George Segal a sample of a quick-drying plaster-bandage for casting broken bones. As Judith E. Stein recounts in her recent biography of dealer Richard Bellamy, Eye of the Sixties, the artist got the idea that he could cover a living body with this material, pop it off, and “have a perfect record of a human being.”

In our second report on “Aha!” moments, Vasari21 members recall breakthrough encounters that range from a lesson from John Cage to advice from an angel.

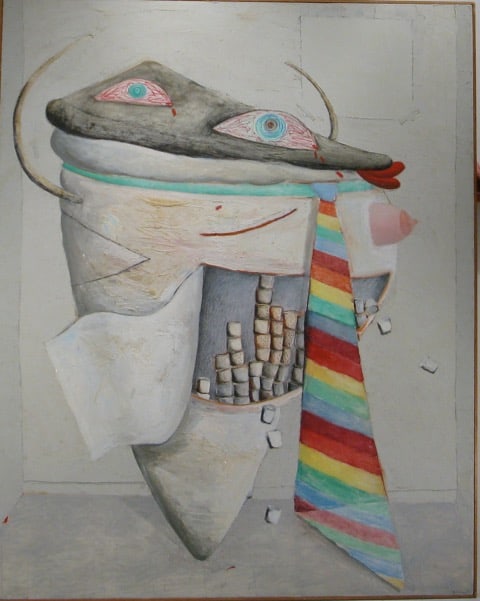

Brenda Goodman

I am 73 and have been painting for 50 years and there has been more than one “Aha” moment. In 1971, about six years after finishing art school (in Detroit) I felt like I wanted my work to be more personal. My mother was diagnosed with lung cancer in that same year. She died the following year and I did a series of works, about my frustration about not knowing how to paint about this great loss. It was the beginning of finding a new vocabulary. I was very tough on the outside and wanted more of my vulnerability to show, so I started creating symbols—one was an abstracted heart because that’s what I wanted to expose. I drew shape after shape until I said “Aha!” This is it. This is me. Then I went on to make symbols for everyone else in my life, including my mother.

That started an eleven-year journey in which my work was like a visual diary of my day-to-day encounters. The symbols were placed in rooms where the dramas would unfold. It was very satisfying to have my work so connected to my feelings but after eleven years they stopped nurturing me and I knew it was time to give them up. That was 1983.

I was a heavy smoker back then and knew how hard it was going to be to quit. The association of painting and smoking was huge, so I stayed out of my studio for nine months and had no idea what would happen when I returned. A year later I took some six-by-eight index cards and started making marks all over them and pulling out shapes that resonated with me and white-outing others. It was so exciting not to know what each was going to look like and it was all intuitive and free-associative. That was another “Aha!” moment.

But as much as I enjoyed working abstractly, I also loved painting the figure and creating narratives. One day I was doing a large abstract painting and small figures appeared that started to tell a story. This was another “Aha!” moment because it brought together the figure and how personal it is in combination with abstraction. That was 1995, and it’s still my favorite way of working.

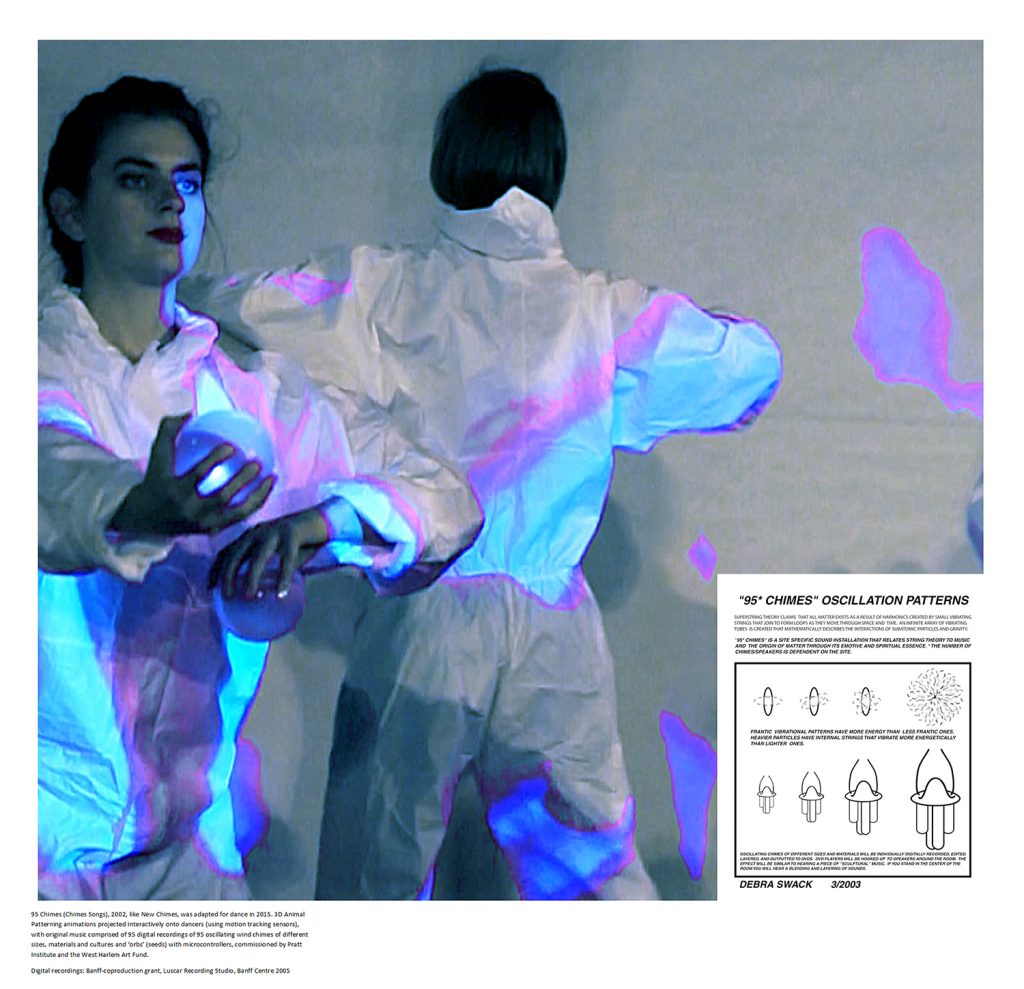

Debra Swack, still from 95 Chimes, presented at the Staller Center for the Arts, 2016, in Stony Brook, NY

Debra Swack

When I was a child growing up in the New York suburbs, I thought trekking into Manhattan to hear music by my father and his colleagues, performed by New York Philharmonic musicians or talented students, was the coolest thing imaginable. My parents, older brother, and I would sit in the audience and later deconstruct each piece played and compare them to similar movements in the arts and politics. (My father had six degrees in music; my mother, a master’s in education; as a family, we always had lively and wide-ranging discussions.) Through my father I met John Cage, who was a collaborator with Henry Cowell, a musician known to crawl inside pianos to pluck at their strings.

Once at a meeting of dedicated musicians, my father walked up to Cage and asked him, “What does your music mean?” and Cage replied, “Does it have to mean anything?” I have been thinking of his comment ever since, and how in addition to chance events, the ethereal and the ordinary not only intermingle in art but in life. Nature, like great art, does not explain itself, but its greatest power is the experience of sometimes unpredictable effects, and perhaps this is what Cage was getting at. In my installation 95 Chimes, I used wind chimes in different sizes and made from many different materials (including shells and bamboo) to relate string theory to music and to the origin of matter. Cage’s notions about chance and meaning underlie the way the action of forces on them—such as wind–determine how the work will ultimately appear and sound.

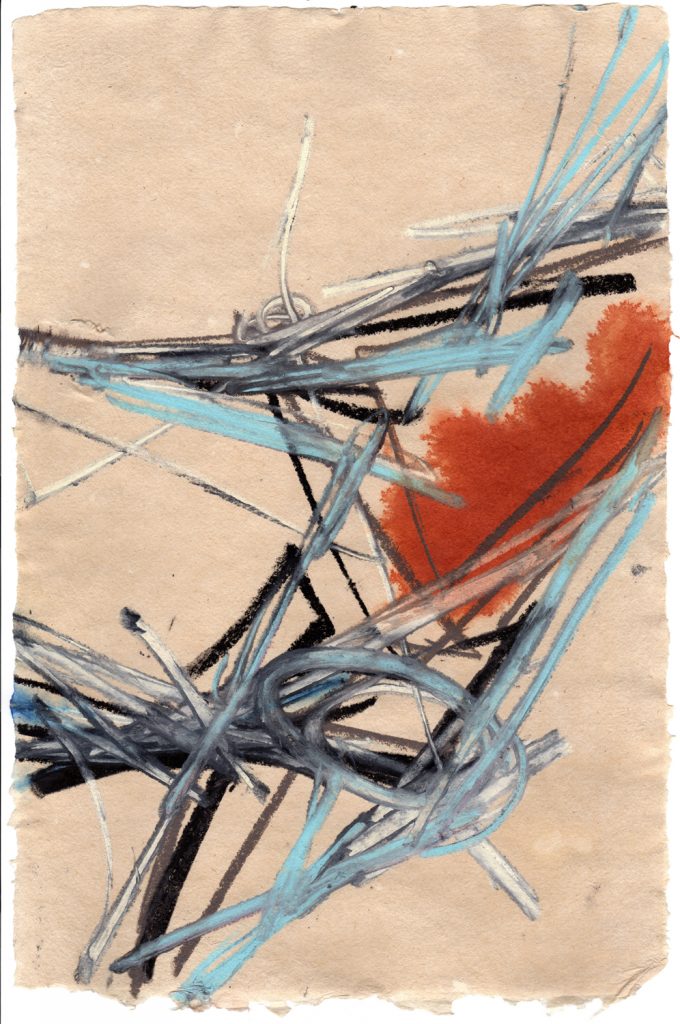

Marieken Cochius

About ten years or so ago, when I was drawing a life model, a friend walked by and remarked, “I didn’t know you were left-handed!”

“I’m not,” I replied, and then looked down at my hands and saw that I was drawing with my left.

When I’m drawing from life, I usually don’t look at the paper. I try to match the speed of my eye with that of my hand, and hadn’t noticed which I was using.

I have since developed drawing with my left hand, consciously, and love using the two different kind of lines I get.

Elizabeth Dworkin

It was the late 1960s. I was young, married, and living in Boston. I had been messing about in the studio, trying to figure out how to be an artist in the same century as Matisse. I was making collages and strange paintings about wallpaper and windows. I remember stirring something on the stove, and suddenly realized I didn’t have to fit color inside an object. It could just be color. I ran downstairs to where I worked, and painted two colors on a small canvas. The pigment stained into the fabric, and when I returned later that night, an abstract painter had been born. And I never looked back.

It was a terrible painting, but it changed my life.

MJ Bono

During my residency at the MacDowell Colony, I watched the seasons changing through my window from inside the studio. The interior furnishings and my figure moving through space were layered as reflections on window surface, overlapping the outside scene. That fascination with inside and outside marked the beginning of an obsession with the window motif and with depicting space, not through perspective or two-dimensions, but through layering on a plane, accidental visual captures, losing and finding forms, playing off canvas edges, flashbacks in memory, and always the push/pull on the surface. I even went back to graduate school and wrote my master’s thesis in 1983 on “the window motif in 20th-century art.”

Annie Coe

In my forties, I was painting animals with acrylics when I read about an artist named Alexandra Eldridge who was using Venetian plaster in her art. I thought that sounded interesting and I went in search of it. After weeks of effort and no success, I decided to give up the quest. But in a dream that night, an angel came to me and said “I hear you have given up on the Venetian plaster.” I said that was so, and the angel retorted, “I would rethink that if I were you.” That dream gave me pause and I redoubled my search, finally locating the medium at Home Depot. After 14 years of working with Venetian plaster I never grow tired of the many gifts it has to offer. It transformed my art and my art practice and I have never looked back. A huge thank you to Alexandra and to the dream angel.

Top image: George Segal, Holocaust Memorial (1984), Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, CA

So fun to read about the different artists and their aha moments. Thanks.

Thank you Ann for including my aha moment. I loved reading them all. xo

Incroyable travail!!!Belle découverte.