Artists Share Moments of Discovery

A few weeks ago, before making the great trans-Taos trek from Cottam Road to Camino del Monte, I asked Vasari21 members if they had ever experienced what I call the “aha!” moment—a sudden realization that a material, a way of working, a subject, or even an idea could lead to a long-term commitment. In the same way, perhaps, as a sudden infatuation leads to lasting love. I gave as examples, Ursula von Rydingsvard’s discovery of cedar beams and Minimalism while in graduate school at Columbia. About her chosen format, Agnes Martin once reported: “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then a grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do, and so I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, this is my vision.”

The answers to that challenge were as various as the artists who responded, and sufficiently lengthy in some cases that I’ve divided this report into two parts, the second to appear next week. (I’m hoping to get some more images too!) And I haven’t yet decided the grand-prize winner for the Agnes Martin catalogue. I may have to put several names into a hat, give a big stir, and close my eyes….

Serena Kovalosky

My first “aha!” moment came at the very beginning of my career as an artist. I knew that sculpture would be the focus of my work and had been exploring a variety of mediums—plaster, clay, bronze, and mixed media—in search of the perfect match for my vision. Most came close, but none truly unleashed the true potential of my art. The revelation unexpectedly came from a most unlikely place–a dinner party during a business trip to Ontario, where I was introduced to a collection of carved and lacquered gourds from Olina, Mexico. Holding one in my hands, I immediately felt a connection that traveled up my arms and exploded in my heart. I had no clue what a gourd was or how to work with it, but I was completely and inexplicably smitten.

My work took off in a bold new direction as I tried to keep up. But I eventually hit a creative wall as I exhausted what I thought was the gourd’s potential as a sculptural medium. I needed to dig deeper, in my psyche and in my work, and wandered back into other mediums to find the key to a breakthrough.

My second “aha!” moment occurred in the middle of the wilderness during a primitive camping excursion with a friend. We were silently canoeing along the shoreline of a secluded lake, immersed in the subtle sounds of nature and the rhythmic splashing of our oars, when my visual perception abruptly changed. As I was admiring the passing scenery, my eyesight suddenly sharpened, colors deepened and the rocks and driftwood and trees were surrounded by a soft “glow.” I could “see” their essence as we floated past and I felt a brief connection to the secrets of the universe—and what many art collectors and curators experience in the presence of an extraordinary work of art. It’s not just about the form, it’s about the place that form can take you.

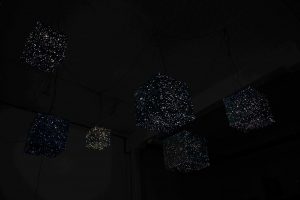

Fred Tomaselli

Fred Tomaselli, Cubic Sky (1998), plexiglass, fluorescent lights, hardware, and darkened room, dimensions variable

Back in the early 1980s, I had a crisis of faith that led me away from paintings and toward installations. My subsequent life as an installation artist went on for a number of years, but I could never completely shake my desire to make pictures. Then, around 1989, I remember thinking a lot about the pre-modernist ideal of paintings as windows to other worlds. This idea assumed that the viewer, while transported into these other worlds, could experience pleasure, altered perception, insight and hints of the sublime. I was struck by how this idealized experience mirrored that of psychedelic drugs and also how both of these worlds were marked by a compromised utopianism. I eventually decided to play with this convergence by inlaying real drugs into panels in order to reroute the pathways that these objects took to altering perception. Instead of entering the mind through the bloodstream, they could now enter the mind through the eyeballs. But how was I going to preserve these water soluble, ephemeral materials? My background in woodworking gave me the skills to inlay these magic objects into the picture plane. And my background in surfboard fabrication gave me the knowledge I needed to encase them in resin. While the impetus behind these works was grounded in art history, personal experience and sociology, it turns out that their execution was grounded in my blue-collar skill set. And lo and behold, I was back to making pictures!

Anne Ferrer

Anne Ferrer, Three Modules (2016), ripstop fabrcs, industrial fan, motion sensors, timers, and score by John Nicholls III, 20′ by 20′ by 13′

To tell the truth, I have an “aha!” moment for each new project I do. If I ever stopped having those magic revelations, I would immediately stop making art. When I stumble into a new form, a new use of a material, or something exciting that provokes a new sculpture, the discovery makes me happy, makes my heart beat faster. Then I forget to eat, sleep, or even be sociable. I feel like a sponge, as I guess most artists do. Terrible situations can cause huge despair, but just as I think it’s as bad as it can get, I grab anything that will trigger new work. That sounds romantic, but the “aha” may often come from a painful aftermath.

The most recent one happened last November, two days after the horrific attacks in Paris. I arrived traumatized at Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, a beautiful artist residency that I had almost cancelled because of a sense of guilt at being in a bucolic setting while the rest of my country was in mourning. How can you still do something as futile as making art when your world is collapsing?

It took me two days to emerge from a coma-like state, during which I started mechanically laying down shapes and colors on paper; I wanted to make a joyful piece, suggesting spring, flowers, something lighthearted, almost as therapy for my sad mood. The place was so beautiful, so inviting, while inside I felt so messed up from what had just happened in Paris.

What shocked me out of my melancholy were the sounds from John Nichols III, a young composer from Chicago who was working on a new piece in the studio next door. The silence, the breathing, the violence, the calm, the storm, the sounds of nature, the train passing next to the studio… everything was there in his music. I was listening, holding my breath, inhaling and exhaling to the different rhythms, stunned by the beautiful sadness of his work. I needed a sound like that to make a new work that would make sense right at this moment of my life. In two weeks, I compulsively filled the studio with huge, beautiful, scary, delicious, carnivorous flowers, with jaws, moving tentacles, and joyful colors. The alchemy between Nicholls and me was there, and it made me think I (we) had achieved a good work.

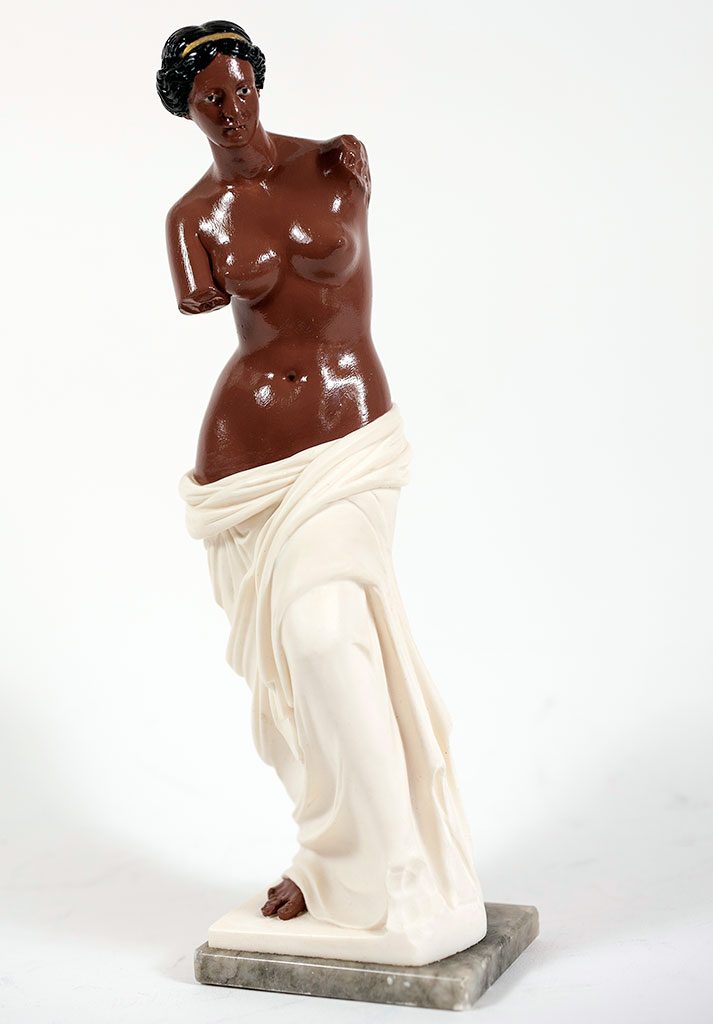

Linda Vallejo

Linda Vallejo, Venus de Milo (2011), 14 kt. gold leaf, repurposed composite, 10.5″ by 3.25″ by 2.75″

Recently, I made a series of trips that included a visit to China, New York, and several major cities in the U.S., where I noticed a growing trend of sculpture made of pre-produced objects, wildly untamed images created from found objects put to fascinating new uses; photographic collages combining digital work and hand drawn forms, and images that juxtaposed seemingly contrary cultural symbols and icons.

In New York I encountered the work of Mexican artist Abraham Cruz-Villegas, who used wire clothes hangers to create a lyrical floating white sculpture reminiscent of Alexander Calder. In China I discovered photographer Wang Qing-Song, who re-purposed Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, using a staged photograph with Chinese models. Ana Mendieta’s solo exhibition at the Hirshhorn in Washington D.C. thoroughly moved me. I was fascinated by her ability to combine what appeared to be incongruent mediums to create an expressive whole.

After studying these works and hundreds more, my thoughts and creative processes began to shift. I found myself ruminating, “What would the world of contemporary images look like from my own personal Mexican-American-Chicano lens? How would I combine new mediums or juxtapose incongruous forms to create an image particular to myself and my heritage?”

In an effort to create a uniquely personal postmodern cultural image, I began taking notes about these ideas of crossing media and culture. I started collecting offbeat items that somehow spoke to me—newspapers, figurines, postcards, photographs—and then storing them in odd little cubby-holes. My goal was to place them into the cauldron of my creative mind to see what images would bubble up.

It occurred to me that I must be the quintessential post-modern American—a woman, a Mexican-American, descended frompoor immigrant grandparents, educated and raising educated children, and essentially living the American dream. Yet even as a third-generation American, like so many others, I remain invisible in the cultural landscape. One day, as I was sitting in a restaurant with an artist friend, I found myself blurting out, “I’ve collected all these images, and I just wanna make ‘em all Mexican, like me!”

On one of my adventures in yet another antiques store I ran across several pages from the original Dick and Jane school primers. I was astounded when I realized that I could simply paint directly on to repurposed images. I whispered some epithet of disbelief and the “Make ‘Em All Mexican” series was born. After I found a statue of the Venus de Milo in a junk store, I actually cried when it came to me that I could create three-dimensional MEAM objects.

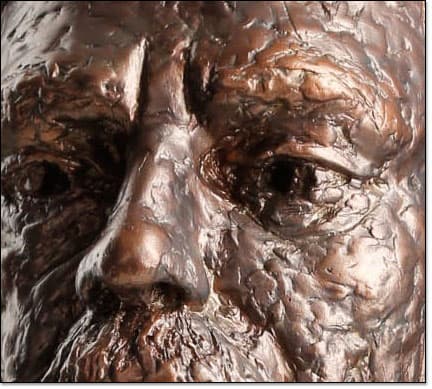

Leah Poller

My “aha” moment took place in Paris, while I was still a student at the Academie des Beaux Arts. My professor encouraged me to visit a foundry outside Paris and experience the important “pour” of a large-scale piece in bronze. The workers were of a single mind: they knew it was a dangerous job, the work of an important artist, and a “never-a-second-chance” occasion to capture the sculpture in bronze. It was a mystical moment, with liquid metal glowing, sparks flying, and the workers like silent monks moving quietly about their work. The pour lasted only a few minutes, but it transformed me forever and led me down the path of bronze as the preferred medium for my work to this day.

Vera Vasek

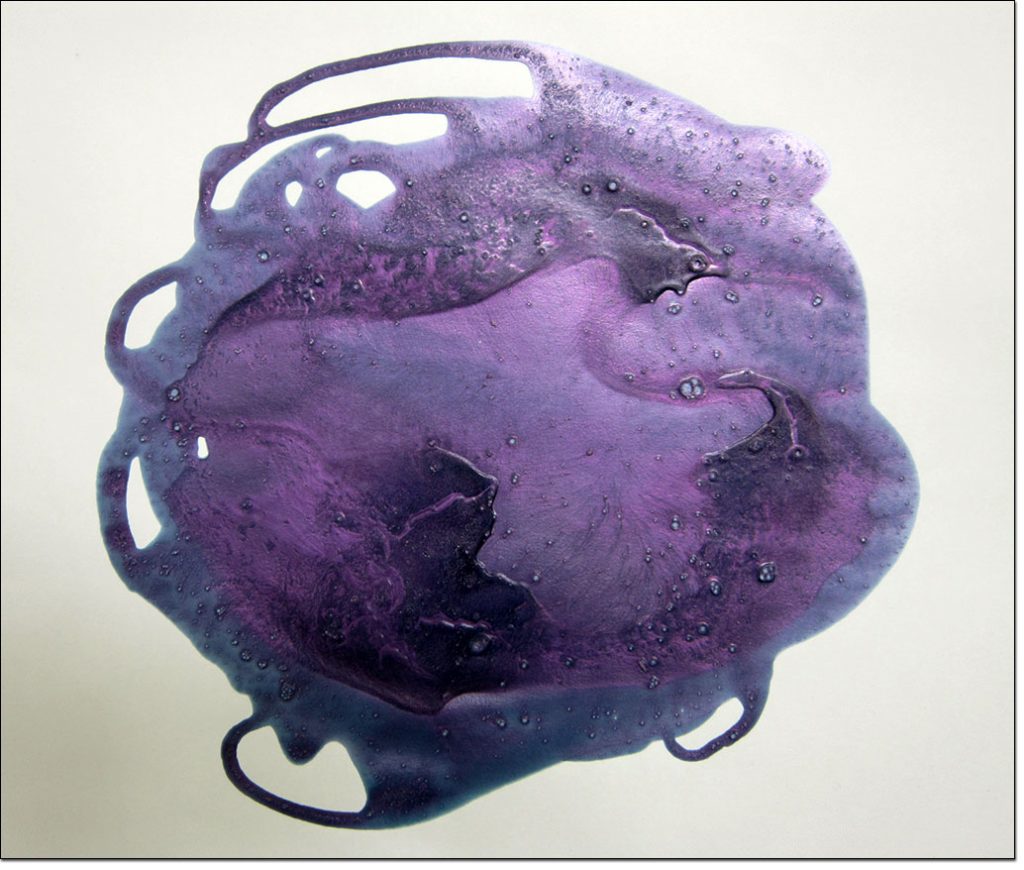

In the early 1990’s, I found myself in the intertidal zone, or back country, of the Florida Keys, pulling plaster images off of relief-like markings in sand that were produced by the tidal flow of water. This work, which I call “Tidal Reliefs,” contains a thin layer of sand transferred from the site from where it was made.

On one early-morning boat excursion into the back country, I experienced the horizon fusing with the mirror-calm water and sky of diffused, blue light. A disorienting and hypnotic effect took over me as I imagined the earth revolving around its axis as it revolved around the sun, and wondered what unseen stars were overhead as our Milky Way galaxy spiraled through the universe. And where was the moon in its influence over the tides? Everything became all mixed up at one at the same time and I was completely immersed in the center. It was all about movement and influence, time and perception. I was taking it all in, and who knew how it would all come out

What began as a form of documenting and collecting tidal imagery evolved into a sculptural practice that consciously moved me from the outside to the inside, to the center of activity where I engage with process: The eventual outcome obtained through physical endurance, observation and chance.

Nol Putnam

After years in the classroom (teaching history), I ventured into decorative arts. I tried wood and did not know enough, nor could I afford the machine tools needed. Wheel-thrown clay was next, only to find I did not care for the wet, nor turning my body Into a pretzel to see the profiles of shapes. I blundered into hot forged iron with the wrong kind of coal, the wrong shaped hammer. But, to watch hot iron move, eventually to my will, under blows from the hammer was mesmerizing! Forty-three years later I still find it so.

Top: Vera Vasek at work on a “Tidal Relief”

Thank you, Ann, for the opportunity to share my “aha” moments and to see how other artists experience theirs. There seems to be a profound “letting go” of what we think we know in most cases, in order to reach that inexplicable moment of revelation, or to stumble upon it on the way to something else. I look forward to reading Part 2!

Ann, Beautiful. Loved this, I have aha moments on almost a daily basis, so lovely to read about other artists and their inspiration.

Dear Ann, Thank you for inviting me to share my “aha” moment. This is that unique moment the artist searches for in every step of their process; that hoped-for second of inspiration after months of thoughtful study and process. I have been inspired by reading these great stories!