Tamar Zinn was about twelve when she discovered the thrill of drawing. Like many artistically inclined New York City kids, she took classes at the Art Students League on West 57th Street. “There was an enormous studio divided into two sections,” she recalls. “In one was a still-life set-up, and you expected either to draw or work in watercolor. That’s where I started, and I found it very boring. But I became really curious about what was on the other side of the studio wall.”

On the other side were the nude models, and students working from the figure, and that exercise seemed to Zinn immensely more appealing than drawing bottles and oranges. Not that the models themselves were particularly attractive—“it was just bodies,” she says. “I was seeing forms and curves and I loved it. There was a freedom in my line that excited me, while working from still life was tedious.”

At that age she had no particular notion of what it meant to be an artist and she ended up at Bronx High School of Science, a prestigious public secondary school because, she says, “my older sister wanted to be a doctor, and I guess I was competing with her. I took every elective art class that I could, which was perhaps a total of three classes over three years. It was just something I did because I enjoyed the process.”

Zinn grew up the daughter of Jewish Socialist parents on the Lower East Side, not far from where her present studio is, and though her parents’ cultural interests tended toward opera and theater, they had a membership to MoMA and frequently took their offspring to museums.

From the time she was a child, Zinn was a talented violinist and studied the instrument for twelve years; when she got to Brooklyn College, she pursued a double major in studio art and music. “I didn’t know what I was going to do after college, so I simply studied what I liked, along with the required liberal arts,” she recalls. “In my sophomore year, I had to take an introductory sculpture class, which terrified me. My fear was irrational, but intense. That sculpture class made me realize that I wanted to pursue art rather than music. I was more willing to be miserable to get to the other side while making a lousy sculpture or a drawing than I was willing to struggle to become a better violinist.”

After college, with no particular skills to market, she ended up working for a neighborhood printer on the Upper West Side, where she became a typesetter in a tiny shop grandly named Gutenberg Printing. Zinn soon began to take on assignments from private clients to design brochures and catalogues, and switched to working part time and painting more often. “I still wasn’t thinking I would be a capital A artist,” she says. “I just painted.”

Then in 1977 she did a summer residency “at a place in Woodstock that doesn’t even exist anymore. For the first time since college I had the opportunity to paint for as many hours a day as I chose, with no one telling me what to do. I discovered that, given the opportunity, painting was all I wanted to do. It was more than just something I enjoyed. It was something I needed to do.”

A few months after that, Zinn walked into Kathryn Markel’s gallery, then on 57th Street, “with a bunch of little watercolors.” She was only 25, but Markel took a shine to her work and has been her dealer ever since. “I later realized how lucky I was,” she says. “I would go around SoHo and drop off slides at galleries, and barely get acknowledged with a nod, let alone a thank you.”

Throughout most of the 1980s and ‘90s Zinn explored an abstracted landscape idiom, often with a rigorous approach. “When I worked in watercolors, I would draw grids in pencil, stacked narrow bands as narrow as an eighth of an inch. And I would paint within each band, let it dry, and then paint another. I always worked from my imagination, even though the works were recognizably landscapes.”

Although Zinn has tried plein-air painting, she says it was like “drawing from those still lifes at the Art Students League—boring, boring, boring.” After 9/11, her focus shifted and moved away from traditional landscape. “The current work is certainly derived from the natural world, but it is never done directly from nature.” A recent body of paintings, for instance, was inspired by the lunar eclipse in fall 2016, which she witnessed firsthand and later studied in photographs. “I liked what I saw in the photos, the range of subtle colors like pinkish and blue grays.”

Zinn’s technique of late has been to apply oil paint to an acrylic gesso ground on panel very systematically, in perpendicular layers, and then drag or scrape across the surface with the edge of a razor blade. Softer edges come from using a brush to press paint into the image. The final painting is extremely subtle, suggesting almost infinite depth, and with a whispery seductiveness that is hard to convey in photos.

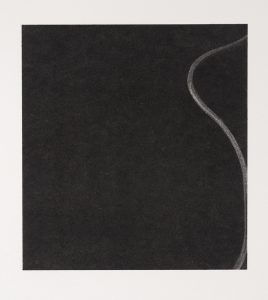

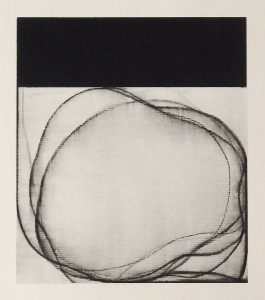

The artist has also recently turned to drawing gently biomorphic shapes, taking a pleasure in mark making that she says goes back to when she was 11 or 12 and drawing from the figure. Part of the reason for turning to line was in response to how she was painting. “I have a very controlled method for painting, and I needed to be doing something where you could feel the motion in the wrist.” Lines are drawn with thick graphite and sometimes black oil pastel, and the impression left behind is one of quivering impatient life, like something struggling to be born.

“I feel that my work is the best it’s ever been,” says Zinn. “It has a lot of strength in it, even if I don’t know where it’s going to go. Although there is still plenty of struggle, I see where I’ve come over the last 15 or 20 years. I’ve finally figured out a few things for myself, and I want to use my time to keep going.”

Ann Landi

Top: A view of Tamar Zinn’s studio

Great to read, Tamar! Work looks great too.. Thanks for posting.. Julie G

Enjoyed your interview, Tamar! Thanks so much for sending it. It was great to see your wonderful work here, and exciting to see the most recent ‘Moonglow,’. Look forward to seeing it in person.

great interview. beautiful work! glad you shared this.-best- doug e.

I enjoyed learning about your background, Tamar. Very interesting. And your work is fabulous!

I like the way Tamar’s work is evocative and dramatic through reduced elements. Was so interesting to hear the story. Dena S.

I’ve known no one more dedicated than Tamar Zinn; what’s often missing for so many with latent talent, to continually evolve. This tells her story well and it’s far from over!

This was so wonderful to read! Your work is beautiful!

Really nice interview and work, great to hear your history through the lens of the Art Students League.

Congratulations on this thought provoking interview. I enjoyed knowing more about your history and how you have invented and reinvented yourself as an artist.

Great background story, enjoyed it very much and of course the work is strong.

Black and white 47 where the upper bar pulls forward……

my favorite. It is that difficult format of being too long and how to compose it. The black is held by the etherial stuff…..dont know why.

Love them all. Paula

Exquisite work, but I especially love the group of biomorphic drawings in the last photo!

Thank you Ann, for writing this profile of me and my work. And thanks to all who took the time to offer such generous comments about my work. Tamar

Very nice.