Installation Artists Continue the Narrative Tradition

Once upon a time, storytelling was one of the most ambitious missions of painting. Panel by panel, Giotto told the lives of Christ and St. Francis. Michelangelo presented the sweeping drama of the Old and New Testaments across the vast expanse of the Sistine Ceiling. Closer to our own times, Diego Rivera celebrated the struggles of the Mexican people, while Thomas Hart Benton created heroic epics with Depression-era characters from the Midwest. With the rise of Modernism in this country and elsewhere, the storytelling impulse among artists seemed to disappear, dismissed as tired, irrelevant, or embarrassingly academic.

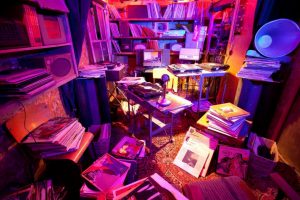

Part of Jamison Charles Banks’ Retour des Cendres/Return of the Ashes Vol. 1 (photo by Eric Swanson, courtesy of Site Santa Fe)

But the drive toward narrative, and an art audience’s fascination with stories, has resurfaced in recent years, often in video but perhaps more evocatively in installations, which invite comparisons with developments in contemporary fiction—shuffled chapters, meandering plot lines, mash-ups of genres, and elusive or unreliable narrators. But the dizzying challenge for the installation artist, as opposed to the filmmaker or wordsmith, is that he or she is free to choose from so many mediums to realize a completed project—video, sound, ready-made props, photography, conventional approaches like drawing and sculpture, and even the great outdoors. How to make it all cohere in a gallery or museum setting, and in the viewer’s mind, is the end goal, and what’s expected of the audience often goes beyond the demands of more traditional art forms. And that can be either an exhilarating trip or an exercise in frustration.

“If I could, I would probably write,” says the Toronto-based artist Iris Häussler. “But I can’t. Some people define my work as novels in three dimensions.” Häussler’s installations center around the lives of fictitious protagonists, whose stories are fleshed out in some detail in documents or even in the words of a tour guide/archivist (often herself) who guides the audience through her creations. One of her more imposing projects, He Named her Amber (2008-2010), took place in a 19th-century house called The Grange, embedded in the Art Gallery of Toronto. Visitors were told that a diary belonging to a butler who worked there recorded the story of an Irish maid who had secretly fashioned and buried a number of objects throughout the building, including a long wax cone and a blob of clay and beeswax the size of a baby’s fist. “A descent to the darkened Grange basement revealed an archeological dig going on full throttle, with bright yellow tape, danger warnings, and three long containers full of soil and rubble,” wrote curator Elizabeth Armstrong, who included parts of Häussler’s project in the exhibition “More Real” last year at Site Santa Fe and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Häussler’s characters are often marginalized, living on the fringes of society. “One thing I’m interested in is that history is told only by survivors,” she says, “and I often wonder what the people who cannot tell their stories would have to say.” Novelists will sometimes claim that their protagonists begin to dictate the story as they are in the process of writing it; Häussler says she experiences something similar: “I do research and these characters start becoming more alive, and I flesh them out, and then they flesh me out, telling me what they want from me.” Occasionally the desire for verisimilitude leads the artist in extreme directions: Because the Irish maid in the “Amber” project was diagnosed with hysterical blindness, Häussler blindfolded herself to create some of the objects in the installation.

Telling the “Lost” Stories

Just as Haüssler’s protagonists hint at alternative ways of understanding history, other artists concern themselves with redressing the record or telling the stories that get lost in the cracks, especially when racial identity plays a part. Long before the recent movie “Twelve Years a Slave” earned high praise for dispensing with the Hollywood stereotypes of lovable masters and cheerful field hands, Kara Walker’s videos, cut-paper silhouettes, and installations zeroed in on an antebellum South of casual violence and unspeakable savagery. Native American artist Jamison Charles Banks, who is at work on a project that connects the sale of the Louisiana Purchase to the eventual exile of the Cherokee people to what he calls “the reclaiming of identity through baseball,” sees it as part of his mission to “enrich the story part of storytelling” handed down for generations of ancestors.

Zoe Beloff’s Dreamland: The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle, 1926-1972 (2009)

History enters into the work of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, who might be considered modern old masters of the installation genre. In their fictional biographies, the Kabakovs’ projects address the rift between communism and capitalism, and in the words of critic Peter Schjeldahl vivify “the soul-killing toll of long oppression.” Allison Smith, who has an eye both on history and the politics of identity, was brought up in Virginia, where she spent a fair amount of her childhood visiting living-history exhibitions and period houses and witnessing Civil War re-enactments. In time she rebelled against what she describes as “the repeated whiteness and masculinity” of those presentations. Her installations combine elements of craft, performance, and participation to raise questions about the history that’s been packaged for us in classrooms and textbooks—such as, were the early American rebels revolutionaries or terrorists? What are the dividing lines between craft, traditionally practiced by women, and art, as in the portraits painted by men? “History is a process we all participate in,” she says, “and if we don’t participate in that process, then we leave it to other people to decide how history is recorded and remembered. So I focus on the kinds of alternative or personal stories that might be less expected, just to open up that process to the public.”

In revisiting history, installation artists find the freedom to mix fact with fiction, and fantasy with real events. In her ambitious and sprawling work “Dreamland: The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle, 1926-1972,” Zoe Beloff used the occasion of Sigmund Freud’s documented visit to the great amusement park, during his only trip to the United States, to create an imaginary organization dedicated to exploring Freud’s legacy in America. Through drawings, films, artifacts, and photographs, Beloff took viewers on a rollercoaster ride through the unconscious of the great man’s devotees (videos of their dreams, for example, showed a young woman acting out her bisexual fantasies or a man dressed as a tame bear, fed and petted by female admirers). “I didn’t want to do just an illustrated project of Coney Island as Freud would have seen it,” says Beloff, whose interests in the link between technology and the imagination have led her to investigations into hysteria, visionaries and mediums, paranormal experiences, and utopian ideas about social progress.

Similarly, real events have served as fodder for some of the installations of the Canadian duo Janet Cardiff and George Bures-Miller. Their 2007 project “The Killing Machine,” which included an electric dental chair and two robotic arms that attacked an invisible prisoner, was in part inspired by the accounts of torture at Abu Ghraib (and in part by a Franz Kafka short story). Thomas Hirschhorn’s Concordia, Concordia, shown in 2012 at Barbara Gladstone, was a helter-skelter room-sized assemblage of replicas of objects from the Costa Concordia, the cruise ship that sank off Italy earlier that year. Scattered across the expanse of the gallery and fastened to walls, like the contents of the boat that had been tipped over by catastrophe, were life preservers, light fixtures, a baby-grand piano, deck chairs, ripped carpeting (as well as a reproduction of Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa). Like a novel by Joyce or Pynchon (or any multi-layered work of fiction, for that matter), the installation invited multiple readings, with critic Jerry Saltz finding in its pell-mell messiness “a double-edged metaphor for the top-heavy operational apparatus of the worldwide art system”—among other interpretations.

If Concordia, Concordia recalled the real-life events of an ill-fated voyage, other installation artists take the audience on fantastic journeys, as richly imaginative as any sci-fi novel or movie. Tom Sachs has staged expeditions to the moon and Mars. Ellen Harvey’s recent Aliens’ Guide to the Ruins of Washington, D.C. imagined the nation’s capital as a destination for what she calls “very confused aliens after we are all gone.” Moriko Mori’s 2003 Wave UFO invited visitors inside a shimmering fiberglass capsule, shaped like an oversized teardrop, where they could have their brain waves analyzed by a computer. And in 2010, Cardiff and Bures-Miller salvaged a 30-foot Chinese junk, transported it to their studio, and turned its cabin into an environment they describe on their website as “an escape route for the viewer into a forgotten world.”

Mixing It Up

Many, if not most, contemporary installation artists turned to the exploding possibilities of using many different mediums after encountering deep dissatisfactions in conventional academic training. “I went to an old-fashioned art school in Edinburgh in the seventies,” says Beloff. “I was interested in storytelling there, and I felt that painting was no longer a storytelling medium and that’s why I got interested in film. Then I ended up in film school, but in the end I didn’t want to make Hollywood or Sundance movies.” Says Haüssler, “When I was a student I was interested in portraiture but I found it absolutely dull and boring to try to put something into two-dimensions or to do a sculpture. But if you go in someone’s drawers and fish around, you come across the things that were really meaningful to someone. What we allow in our private sphere tells a lot about the condition of our soul and our personalities.” Film often presents opportunities for the narrative-driven artist, but those who turn their backs on the movies, or see them as too limiting, cite the reasons installation in all its flexibility appeals. “I wanted to tell my own stories in a way that I don’t think is possible in commercial cinema,” says Beloff. “What’s great about the art world, as opposed to Hollywood or even most independent cinema, is that we have the freedom not to have to work with a lot of other people,” says Bures-Miller. “We have the freedom of the audience being open to change and difference. We don’t like to stick to making the same things over and over”—as would many a Hollywood director to establish his or her reputation.

Ellen Harvey’s Alien Souvenir Stand from “The Aliens’ Guide to the Ruins of Washington, D.C.” (2013)

Any work designated “installation” can demand a lot of the viewer. You’re asked to connect the dots, make sense of an array of disparate objects, and perhaps inject your own stories. There is the danger of any agglomeration of stuff tipping over into what Saltz called clusterfuck esthetics—“[T]he practice of mounting sprawling, often infinitely organized, jam-packed carnivalesque installations is making more and more galleries and museums feel like department stores, junkyards, and disaster films,” he noted in 2005. But when the “narrative” works, the results can be pure enchantment. This writer still remembers seeing Cardiff and Bures-Miller’s Opera for a Small Room several years ago. Inside a huge cratelike container—actually a room recreated from a farm the couple had bought in Canada—the artists had positioned 24 antique loudspeakers playing random sounds, arias, and pop tunes. Also scattered about were 2,000 recordings and eight record players which switched on and off, along with tattered furniture, chandeliers, and other props, all belonging to a character known only as R. Dennehy. The illusion of a real person was reinforced by mechanically generated shadows and a narrator who said things like “He waits in his room, playing his records over and over. It helps in some way he doesn’t understand.” The piece takes about 20 minutes to absorb in its entirety and conjures a wealth of associations and stories about a lonely recluse who finds solace in his marathon collection of recordings. It’s a scenario that can linger in the mind longer than any episode from a book or movie. But you won’t find it in your local library or multiplex.

Ann Landi

Top: From Iris Häussler’s installation The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach (2006)

What a great read-,none of the artists had I known about and now I want to know more about each. The question of narrative has interested me for so long as has the push pull of writing vs the visual language. Installation work does have that full range from immersion to chaos. Thanks for this essay