More reactions to the ugly zeitgeist

We’ve now had a full year to take stock of the current administration in Washington and, as Melissa Stern points out, “Every day brings a new outrage, a new affront to common decency, an erosion of our democracy.” Some artists see their work as a necessary retreat from the unhappiness in the world at large. Others are pushed into more activist roles. But no one, it seems, is entirely immune to a climate of lies, deceit, racism, misogyny, and threats to the fundamental underpinnings of our way of life.

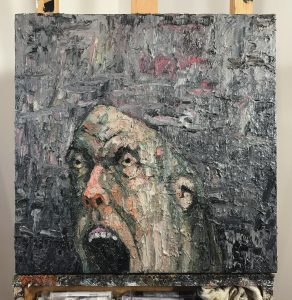

James Deeb

Most of my work, while not overtly political, deals with the human condition. I’m particularly interested human folly, although not in an accusatory way. My work is executed with pathos and a bit of dark humor. We’re all in the same boat, after all. If anything, the current climate lends credence to ideas that I’ve been working with for a long time. I’m not suggesting, however, that I gain any satisfaction from saying, “I told you so.”

The more pressing issue, in my opinion, is self-censorship in the art community. Whether it stems from a desire to escape or to not make waves, I fear that many will preemptively silence themselves as the struggle intensifies. I remember feeling the same chill early in the presidency of George W. Bush. I imagine some older artists would say the same about the presidencies of Reagan and Nixon. (And shame on those who wax nostalgic about Bush. Donald Trump, who is very likely a traitor, is not a war criminal…not yet, anyway.)

My developing strategy is to find alternative venues to host pop-up shows. My friends and I have organized two benefit exhibitions so far, with most of the money from sales going to charities and foundations that are working to stop or limit the damage being done by the current administration. Putting art in people’s homes and giving to worthy causes is a small victory for all involved.

One last bit of advice: Resist, but maintain a sense of humor. Perceiving everything as a dire emergency is exhausting. And exhaustion easily gives way to despair.

Virginia Katz

Virginia Katz, Recomposition with Topaz, Amethyst, Ametrine and Quartz Crystals, detail (2017), acrylic on panel, 16 by 20 by 5 inches

The political climate is influential in my work and is one element that is factored into it. My more recent paintings look even more intently at our profound connection to our environment. This direction is the result of my own life experience.

I have been focusing on debris fields as a metaphor for personal as well as societal chaos, tribulation, and the sublime. As a conceptual painter, I am thinking about the range between light and darkness, colorlessness and monochromatic palettes, as well as transparency and physicality. My intention is to provide some experiential reckoning in the viewer.

Since the individual is part of humanity and humanity is literally intertwined with the landscape, decisions we make within the political/social realm have a direct impact on how we experience landscape and live in our world.

Melissa Stern

This has been a terribly difficult year for artists. Making art takes a certain amount of emotional energy and concentration. One of the reasons people are so keen to go to artists’ retreats is that it gives you a respite from the world—all you have to do is concentrate on making art. Even in “normal” times the world has a way of barging into an artist’s day and throwing distraction in one’s path. This year the distractions have come fast and furious. Every day brings a new outrage, a new affront to common decency, an erosion of our democracy. If you are a person who cares about the world, I would bet that, like me, this has been a hard year to concentrate. Accustomed to reading The New York Times every morning, I find myself leafing through the news section, reading the headlines and a few paragraphs, and then moving on to the arts, science and food sections. To read the whole news section would be too depressing, and render me unable to work. It has been hard to concentrate on art-making, when some days it seems so trivial compared to the strife in the world. I find that i need to discipline myself to turn off the computer, turn away from the events of the day, crank the music in the studio and work at finding that special psychological spot where I can focus. It ain’t easy.

Jan Anders Nelson

The current climate is atrocious. The increasing divisions I feel sweeping across this country and elsewhere challenge me daily, and I imagine that they will surface in my art. A lot of my work tends to have a subtext that can be read as carrying a socio-political commentary. In part that stems from my coming of age as an artist as some of Pop was showing consumer banality against a backdrop of a rising awareness of the impact of the waste streams coming from mass-produced, throw-away consumerism. I consider myself an advocate for what many call environmentalism, which is conflated with being a left-leaning political point of view. I feel that sustainability is actually conservative by design. There are so many other dimensions of social discourse right now that are also of deep concern for me. At the top of my list is how patriarchy is fighting fiercely against gender, how men who share my “ethnicity” and “generation” are being called out for behavior that is abhorrent to me. I struggle with how to deal with that, with how so many men can be so predatory, believe it to be right and role in society. I have been working on a drawing of my wife, from a time when we were very young and falling in love. It is probably my way of internalizing my feelings and perhaps demonstrating my profound respect for her. I am not sure what I want to do to voice my distress over where we are. I imagine it will bleed through the work over time.

Millicent Young

Millicent Young, Cantos for the Anthropocene: 22-29 (2017), lead, wax, washi paper, ink, pigment, wire and steel bolts, 31 by 32 by 3 inches

These political times don’t seem horrific to me but, instead, predictable, expectable, and explainable. An outcome of all we have done. I’ve heard that whine from too many and I have no patience with it. Why is it “hard to make art in hard times”? What are “good times”? Ahhhh, America.

My lens has a different focus—not only on the absurdity of our national political TV show and the pathos of our social malaise—but on the Anthropocene which, if we could get beyond our puerile national id, is much more important. We are in a time of the complete unknown. Are we terminal or not? That is what terrifies us but we turn to the ridiculousness of American politics for diversion, as an addiction, as a perverse indulgence, and it’s a steady drip.

The Anthropocene is Now—as defined, it is the epoch we are living in—the sixth great extinction. Not set into motion by meteors or other natural catacylsms. This one is our doing alone. Not shrugged off by a cultural brush—”empires come, empires go”—the very foundations of what we named Life are meeting their demise by our actions.

“Extinction” is a large word of such vast scale that we cannot connect. We are a culture in denial of death—the second thing we all do—of aging even, so extinction is beyond the American imagination, beyond the American heart. To be a witness to death is to change the field in which it is happening. That effect is extraordinary because it is done with open eyes.

I am compelled to make work as a witness to our time, to what is vanishing. To shape a language for what we cannot grasp or utter. To not pretend. To affect the field of perception. To speak my love to the dying. To say I am sorry. To remember. To be in awe.

Mary Mendla

My creative spirit is a source of joy and healing for me. I protect my creative space and time very carefully. I work hard to protect myself from chaotic, negative, and violent energy, and to keep it from infecting my center. I feel it is a large part of an artist’s calling to bring healing energy into the world.

The violent racism that we are experiencing, especially in our country, but also in other parts of the world, continually asserts itself in horrendous acts that are impossible to process without being pulled off center. I keep myself protected from most of the usual news venues as much as possible. I am not called to be an activist. I feel activism keeps one mired in anger and hatred, albeit from the “good” side of an issue. There is definitely a place for activism if a solution can be accomplished through participation, but it seems to me that in these times activism does more to create negative effects than positive. I believe I can impact our times best by trying to keep my energies pure, practicing non-judgment and communicating a sense of peace and healing through my art and teaching.

Sadness comes through often as I paint, because of the repeated news of hateful acts in the world. I allow these to pass through, knowing that I am so very fortunate to have my art as an essential part of my being. My images are peaceful, relating to land, sea or sky with a sense of quiet introspection. This is healing to me. I often post images of my paintings on social networks at times of traumatic world events with the simple caption of “Art heals” as an attempt to reach out with this message.

Patricia Moss-Vreeland

Thinking about the word activism—which has come to take on greater meaning during these stressful times—I have been involved with tackling more visible, controversial issues, whether they are political or environmental. One group of works called “Colliding Fields” addresses environmental impact. I focus on the habitats that we endanger, and therefore the animals that find homes in these places, which are now compromised. The energy that we produce and use, and its effects on our resources, the land and air, how this all interacts without concern, sadly, for any of the inhabitants of the planet. I paint and draw to point to this kind of isolation, with some glimmer of hope that the work might elicit empathy and perhaps some action on the part of the viewer.

I see my still-life compositions as a way of bringing a sense of an underlying order to relationships, and my prints bring out the reality and importance of memory, of making connections through the use of metaphor. I have also grown my social art practice, which I initiated four years ago, as a form of political activism to get people to talk, to participate. I had thought of ways of reaching out to people with a basic premise, the connection of food to memory, and expanding on my much earlier discovery that memory is a portal to one’s creativity. I feel deeply that if we can connect in these ways, we can build bridges among individuals and communities.

Jamie Hamilton

Jamie Hamilton, Echo Chamber (2017-18), aluminum nylon dichroic glass rubber acrylic LED, 34″h by 24″w by 24″d

In these times I am reminded of the importance of truth and the simultaneous paradox of defining truth. In her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt tells how in eras where truth and lies become indistinguishable, people feel isolated and the dormant seeds of totalitarianism take root.

If any time in my life seems to echo Arendt’s warning, it is now. The internet has allowed an unparalleled volume of publication. Voices appear, but as apparitions, encodings, residents of electro-magnetism, whom we can only understand through the interpretations of machines. A prevalent lack of trust has emerged, while simultaneously the desire to know remains.

I feel democracy is in crisis. It always has been, so perfectly vulnerable it is to lies. However fundamental injustices, ones which a functioning democracy is supposed to guard against, are increasingly difficult to ignore. My current work is a response to my theory that the underlying structures that are causing this crisis are left largely uninterrogated. I observe the way our attention seems to condense like mass pulled together by gravity. Publicly regulated services like phones and mail, used for disseminating personal and public information, are being replaced by platforms owned by corporations, obscure in their design. I see the haste with which we bolster social media, so stressed are we to survive or to gain influence that we perceive our participation in it as an absolute necessity.

How do I align myself now? I choose to make art, a record of my life and the times I live in. Perhaps some of my endeavors are irrelevant and eventually end in a scrap yard, or they are relevant and seen, or they become treasured. The hegemony of an art world is random, so at times is “justice” “liberty” and “truth.” My flesh will decay, my bones will turn to dust—that much is certain. But I have another certainty, and that’s that how one spends attention matters. It is the attention in making art that carries my love through times of delusion and pain. When we see more clearly we have less to fear.

Top: I find it curious that Jan Anders Nelson’s American Landscape (1974, graphite, 23 by 29 inches) dates back to another period of chaos and corruption, around the time of the Watergate debacle that brought down Richard Nixon.

Such a fascinating collection of responses in both part 1 & 2. But I am particularly moved by Jamie Hamilton’s piece, how poetic and clearly expressed and how succinctly placed in a larger context….very resonant.

Great blog. Interesting to read other artists’ perspectives on how they respond to our times. Millicent Young’s response seems particularly apt in light of humanity’s current ability to destroy on an unprecedented and terrifying level.

All featured here were able to express through art what so many of us have been feeling.

Thanks so much, yes it’s been a difficult year.

Wonderful to hear their ideas. Thanks for providing this forum.