Francis Picabia was a man way ahead of his times. Long before artists of our day became dedicated multitaskers—moving easily from performance to sculpture to video to whatever—Picabia (1879-1953) vigorously avoided any singular style or medium, forging a career that encompassed Impressionism, radical abstraction, Dadaist provocations, photo-based realism, poetry, and film. And much of it was pretty damn good.

He was a wild and crazy guy in his private life as well, with a passion for fast expensive cars, heavy drinking, and opium. At 18, he quit school and ran off to Switzerland with the mistress of a Parisian journalist. By the time he met Marcel Duchamp in 1911-12, “he went to smoke opium almost every night. It was a rare thing, even then,” as Calvin Tomkins reported in his excellent 1996 biography of Duchamp. “’With [Picabia], it was always, ‘Yes, but…’ and ‘No, but…,’” his fellow Dadaist recalled. “’Whatever you said, he contradicted. It was his game.’”

His career seemed to unfold along much the same lines. The son of a French mother and a Cuban father (“himself a notorious roué and man-about-town,” according to Tomkins), Picabia was independently wealthy from a young age. But he was not quite as undisciplined as many stories would suggest. He studied painting seriously for five or six years in Paris, and made a name for himself with a show of retardataire but accomplished Impressionist canvases. By 1911 he was shifting back and forth among recent avant-garde styles, producing some rather lame Fauvist landscapes, like Landscape at Cassis, and radically simplified but clumsy portraits evidently influenced by early Cubism.

Then around 1913 he suddenly and dramatically burst away from pastiche, painting explosive works, like the ten-foot-square Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic), now at the Art Institute of Chicago, and I See Again in Memory My Dear Udnie (MoMA), also an outsized statement at eight by six feet. Both deploy a highly original vocabulary of colors and shapes, which seem derived from a fascination with high-powered machinery as well as abstracted organic forms. Seven years later in a riotously anarchic moment, and in what seemed a complete about-face, Picabia nailed a toy stuffed monkey to a piece of cardboard and called it Natures Mortes: Portrait of Cézanne, Portrait of Renoir, Portrait of Rembrandt.

In between, he traveled to New York City several times, becoming involved with Alfred Stieglitz’s pioneering gallery and magazine 291 and attending Mabel Dodge Luhan’s weekly soirées at her Greenwich Village apartment. During the war years, “Picabia had managed to stay out of the trenches by getting himself posted as chauffeur to a French general who happened to be an old friend of his father-in-law,” Tomkins reported. He also managed to tuck in an affair with Isadora Duncan, launch a magazine called 391, and continue a pattern of drinking and strange behavior that would eventually lead to a nervous breakdown.

Natures Mortes: Portrait of Cezanne, Portrait of Renoir, Portrait of Rembrandt (1920). toy monkey and oil on cardboard, whereabouts unknown

Seeking treatment for depression in Zurich, Picabia met up with Dada ringleader Tristan Tzara, whose radical ideas were tailor-made for this most restless of artists. He published poems and machine drawings in Dada magazines, but eventually gravitated to Surrealist circles, only to turn on the movement a few year later, denouncing Andre Breton’s First Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. That same year he acted in a film by René Clair and somehow pulled together an avant-garde ballet with music by Erik Satie. “For all of his self-contradictions and abrupt changes of course…, his bedrock commitment to spontaneous, unplanned, untheorized, individual experience never wavered, and in this sense he remained, all his life, a true Dadaist,” Tomkins noted in Duchamp.

In his forties and fifties, he returned to figurative art, and toward the end of his life moved to the south of France, where he produced a series of paintings based on nude glamour photos from popular French erotica, like raunchy magazines, postcards, and photo-novels. Shown at Hauser & Wirth in London in 2006, the works seem to anticipate the smirky highbrow porn of John Currin.

If you are curious to learn more about this protean and untamed character, who never quite achieved the art-historical superstar status of his near contemporaries in the School of Paris—Matisse, Picasso, Mondrian, Bonnard, et al.–a full-dress retrospective is on its way to the Museum of Modern Art this November (through March 19, 2017). It looks like it will be a rich opportunity to re-assess an erratic but always intriguing career.

Ann Landi

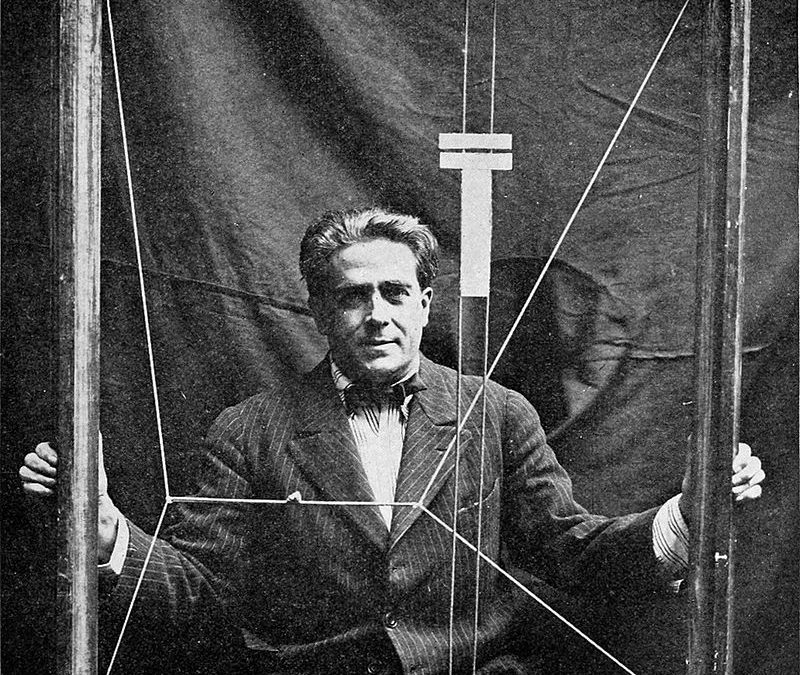

Top Image: Francis Picabia in 1919

This was a wonderful piece. I love his work. Thank you for turning me on. I’m looking forward to his retrospective at MOMA.