Reflecting on Vermeer

By Riad Miah“Every work of art causes the receiver to enter into a certain kind of relationship both with him who produced, or is producing, the art, and with all those who, simultaneously, previously, or subsequently, receive the same artistic impression.”

Leo Tolstoy, What Is Art? (1896), translated by Aylmer Maude (1900).

For years I’ve looked at different works by countless artists. I’ve looked at different objects from all different periods of time—ancient, Renaissance, modern, post-war, contemporary, along with the efforts of teachers, friends, and colleagues. It is part of an artist’s job to keep looking, to see, and to question as much as possible. Through the process, one defines what’s most important and in turn develops an individual aesthetic.

In my ongoing research, there are only a few artists I keep returning to because their works resonate with me. There are a handful I appreciate that have helped carve my own approach, and these are the ones I keep learning from the most. One of those is Johannes Vermeer. What is it about his paintings that keeps me enthralled? For one thing, they are open invitations to looking long and carefully. And the act of looking and investigating, combing through the details of his paintings are at the core of what I find so sustaining.

In a world where we can find boundless information on anything we are looking for at our fingertips and just a few clicks away, it is satisfying to look at a painting by Vermeer and slow down time and focus on just a few bits of visual information. When I look at into his world, I like to think I am gazing back into time. He manages to construct an ideal that is at once reflective of its own time and a vision of timelessness. The images depict moments where composition, tonal qualities, and light help to achieve moments of perfection. But Vermeer’s paintings captivate and hold the viewer’s attention only if you allow yourself to accept the invitation. His work may raise many questions for his viewers—not the least of which is what is going on inside that frame. And then again, we may want to be emotionally ensconced in the works, a part of his world. Once you begin to look carefully, it becomes easy to get lost in the subtle details. Patience and time are the mandatory.

Vermeer’s paintings summon his audience in the same way as an electrifying speaker or a seductive piece of music. One might imagine the size of the paintings to be quite large, meant for a large audience, by the depth they offer. However, the ideal number of viewers to look onto one of his works is simply: one. Vermeer painted intimate moments on a private scale. When we look at most of his works we experience a familiar time—a moment of quietude, isolation, and of reflection. They are incubators of an instant, right before it has vanished. Yet if we could hold on to it, we would lose its preciousness because it is the fleeting nature of the subjects that makes this experience so unique.

The longer one looks at a Vermeer painting the more we see the subtleties required to make the work look seamless. The careful organization and balance are meant to convince the viewer of everlasting permanence. There is a simultaneous contrast between a fictitiously constructed space and that of believability. One of the most striking paintings is Woman Holding a Balance. The soft light caresses the details in the room. The light first passes through and illuminates the yellow in the curtain. The light bathes the room, revealing details in spaces that could not possibly come from a window of such a size, and yet we are convinced it does.

These provoke speculations about what the balance means, what is the significance of the painting of the Last Judgment behind her, the jewelry, the use of perspective? Art historians have dissected this painting to tease out the meaning behind the various elements. But perhaps the real meaning lies in the artist’s ongoing engagement with the viewer. Vermeer’s work continues to invite us to observe and to look, to question and to reflect. It is a rare opportunity to find the time to go to a museum of thousands works of art to look at just one, but to look at only one object at a time a worth it the effort. Johannes Vermeer’s work occupies my attention and holds it, time and again.

Riad Miah

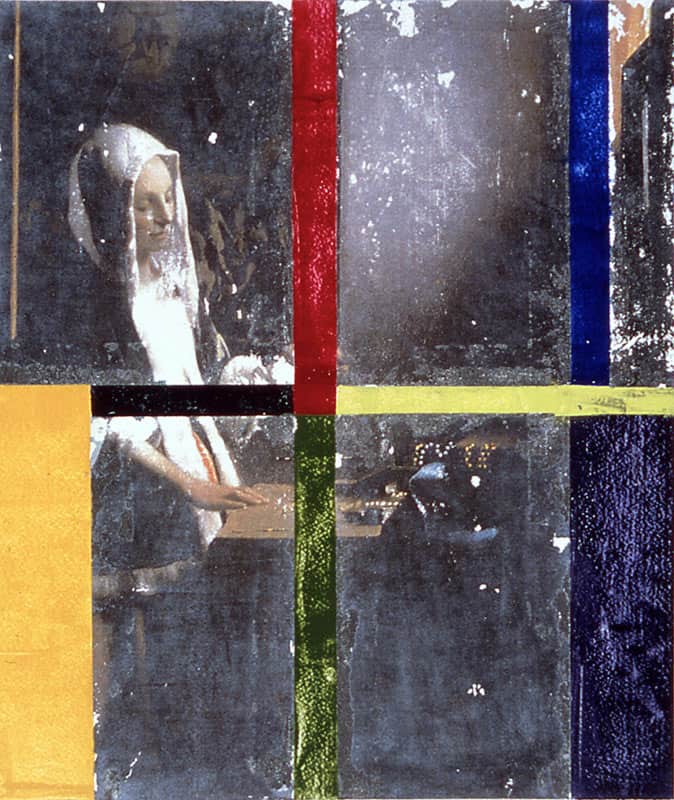

Riad Miah’s last essay for Vasari21 was “A Tribute to Jake Berthot.” Shown here is a work made around 1998, while he was still in graduate school, made from oil, wax, and color Xerox transfer on paper. “I included the horizontal bands so they may look like blinds as one would see peering through a window into his time,” says Miah. “For the Woman Holding A Balance I was thinking about the idea of balance and what it meant in painting at the time.” An artist and educator who lives and works in New York City. Miah has been a professor of art at various colleges and universities, including the School of Visual Arts, Parsons School of Design, and Ohio State University. His work has been exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Contemporary Art, White Box Gallery, Rooster Contemporary Art, and Simon Gallery, and he will be part of a forthcoming show at Lesley Heller Workspace in New York.

Riad Miah’s last essay for Vasari21 was “A Tribute to Jake Berthot.” Shown here is a work made around 1998, while he was still in graduate school, made from oil, wax, and color Xerox transfer on paper. “I included the horizontal bands so they may look like blinds as one would see peering through a window into his time,” says Miah. “For the Woman Holding A Balance I was thinking about the idea of balance and what it meant in painting at the time.” An artist and educator who lives and works in New York City. Miah has been a professor of art at various colleges and universities, including the School of Visual Arts, Parsons School of Design, and Ohio State University. His work has been exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Contemporary Art, White Box Gallery, Rooster Contemporary Art, and Simon Gallery, and he will be part of a forthcoming show at Lesley Heller Workspace in New York.

Photo credits: Woman with a Pearl Necklace (1662-64), Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

Love Vermeer and totally agree, he is one of those artists that I never tire of. The relatively few paintings he left behind are exquisite jewels.

I seriously love your website.. Pleasant colors & theme. Did you develop this website yourself? Please reply back as I’m hoping to create my own personal blog and want to learn where you got this from or exactly what the theme is called. Many thanks!

Yes. I worked with my designer, Susan Preston of Clearly Presentable, on developing the content and design.