Phillis Ideal knows how to do a wonderful studio visit and interview.

I meant to begin this profile in standard journalese, saying something like: Phillis Ideal is a trim, stylish woman with punkishly cropped blonde hair and a wide appealing smile. Or Phillis Ideal works in a spacious light-filled studio at the southern limits of Santa Fe. Or Phillis Ideal has been through numerous transformations in the course of her career before arriving at a playful and exuberant approach to abstraction. And all of those statements are true. But what I realized later was how carefully she had planned our visit, taking me from a painting made as a child, through a history of her work stored on the computer, through up-to-the-minute paintings in progress in her studio. All in an engaging hour and a half.

So I offer this brief initial entrée as a kind of object lesson and complement to the piece on studio visits posted earlier.

But let’s get to Phillis–

A little painting of a bouquet of flowers, made when she was still a small child, hangs in her living room. After her father’s death, when Ideal was a baby, her grandmother became the primary caregiver because her mother traveled often in her work as a buyer for an upscale clothing store in Roswell, NM, then a more thriving community than it is now (wealthy tuberculosis patients settled in the town, mistakenly thinking the dry climate would cure the disease). Her grandmother was a dedicated gardener and artist, who worked on paintings of flowers in the afternoon. “She set up small still lifes for me, taught me how to place my oil paints on a little palette, and how to use turpentine and damar varnish,” Ideal recalls. “I was in her charge and mimicked everything she did. Starting when I was four years old, she taught me about a work ethic.”

Later, as an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, Ideal majored in art and psychology and went on to get a master’s in psychology at New York University. Her professors urged her toward a doctorate, but she fell in love, married, and moved to the Bay Area. She and her husband became involved in the politics of the late ‘60s, which included working as Vista volunteers to help migrant workers in Merced. After moving to Berkeley, she took drawing classes at night to “get back in, and whatever I was doing as an undergraduate, I picked up exactly at that place.” In time, she would enter the MFA program, where she studied with Elmer Bischoff and Peter Voulkos.

Like many in those heady years of consciousness-raising, Ideal also met regularly with a women’s group. “We were totally into the feminist agenda, but we were independent,” she recalls. “They weren’t letting women teach at that point, and we were successful in supporting one another’s art and in getting our acts together to apply for jobs.”

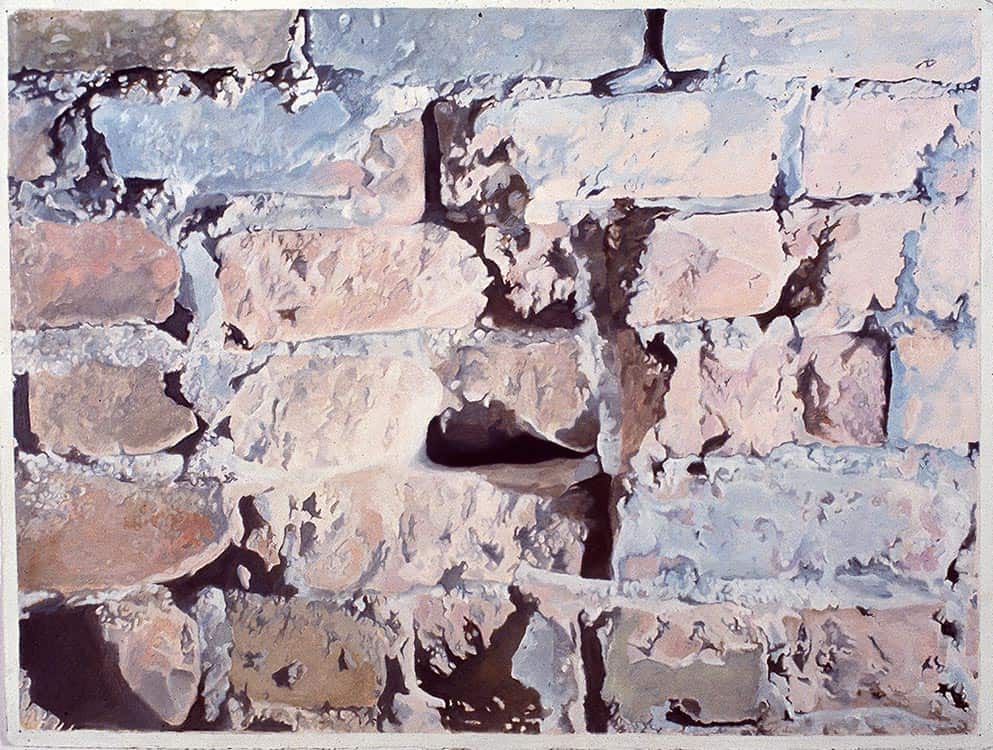

After about five years on the West Coast, Ideal was sufficiently accomplished to land a one-person show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Her works from those years do not reflect an obviously feminist bent, except on an obliquely metaphoric level. She did a series of hyper-realistic brick walls in pastels, sensuously but harshly textured, that might speak of “hitting a brick wall” or feeling “walled in.” At that point, her marriage was ending. “I was using objects to talk about emotions.” These were followed by a series of pastels of pushpins casting ominous shadows—they are “sort of funereal,” she notes—which were featured in the de Young show.

In time San Francisco seemed too confining for young artists and many of her friends were moving to New York. Ideal decamped too in 1982, to SoHo, and her work moved ever more toward complete abstraction. One series of paintings depicted vaguely architectural shapes, possibly parts of adobe buildings, based in actuality on little models made from Sculpey; another referenced the Hispanic tradition of small devotional paintings known as retablos. Both reflected her New Mexican roots. (In the early ‘80s Ideal bought a house in Albuquerque and has divided her time between the Southwest and New York ever since.)

And then beginning in the late ‘80s her paintings became more gestural, evolving gradually into the vocabulary of shapes and colors she uses today. She has experimented with pours and collage and monoprints and most recently iPhone drawings. All exude a sense of spontaneity and joy, even loopy comic energy. If there seems a discontinuity between the realism of her earliest work and now—and who says an artist has to be consistent? just look at Picasso—there are nonetheless common threads running through four decades of drawing and painting. A bent toward abstraction is evident as early as the brick wall series; works on a modest scale, like both the walls and the pushpins, loom ominously large. Tiny Sculpey models are blown up into big shapes. And even today Ideal’s smaller paintings are what she calls “big little paintings”—explode with the same generosity as works that are six by seven feet.

Since her twenties, though, the artist’s work has radiated confidence and accomplishment. If she doesn’t progress from A to Z, as some do, building on small discoveries year after year, she also never looks dated (like so much hyper-realism or so-called feminist art from the 1970s, for example).

And to move with ease from one decade to another is no small feat. Just look at Picasso.

Ann Landi

Phillis Ideal divides her time between New York and Santa Fe, and has exhibited in major museums and galleries in San Francisco, Santa Fe, and New York City. Her work has been shown and collected in many private, corporate, and public collections such as the Oakland Museum of Fine Arts, Newport Harbor Art Museum, and the Fine Arts Museum of Santa Fe. In recent years she has exhibited her work in Otranto, Italy; Berlin; and Paris. She is currently represented by David Richard Gallery in Santa Fe and Is an exhibiting member of the American Abstract Artists.

Phillis Ideal divides her time between New York and Santa Fe, and has exhibited in major museums and galleries in San Francisco, Santa Fe, and New York City. Her work has been shown and collected in many private, corporate, and public collections such as the Oakland Museum of Fine Arts, Newport Harbor Art Museum, and the Fine Arts Museum of Santa Fe. In recent years she has exhibited her work in Otranto, Italy; Berlin; and Paris. She is currently represented by David Richard Gallery in Santa Fe and Is an exhibiting member of the American Abstract Artists.

Photo credit: Off the Deep End (2012), acrylic, wire, and collage on canvas, 72 by 84 inches | Gene Peach portrait of Phillis Ideal.

Thank for the post, I enjoyed reading about Phillis Ideal!

Love this and Phillis and her work.

ah, I wanted to read more about Phillis and her history! Thanks for the trip, though.

It’s nice to read about an artist who’s zigged and zagged her way forward through the ideas that engage her, rather than taking a linear course from A to Z. Thanks for this post!

Great to see this! And I, too, can imagine a longer piece. More images, more story. Phillis is such a terrific painter and has been at it for so long. I’ve seen so many wonderful phases and paintings over the years.

What a great interview. Phillis’s work appeals to me so much more because of her staccato evolution! I think that’s life!!! Note: I especially loved how she learned about art and the work ethic from her Gramma. I had the exact same upbringing except, my mom was also an artist. That stuff matters when your young!

I love Phyllis Ideal’s work too (and Mary Zeran, I can see why you feel a connection with your work and life!). Thanks for the new link in the latest newsletter, Ann. I read the article the first time, but it’s always fun to reread—I seem to find something new each time. Your writing is so clear and well written yet packed with enough information and insight that a 2nd or 3rd reading is always well worth it!!!