Though she now lives in Santa Fe, at a safe remove from severe tropical storms, Paula Roland knows a thing or two about hurricanes. “All my life it was ‘Hurricane’s coming! School’s out!’” she recalls of her childhood in Biloxi, MS. “You cover the windows, pile up the outdoor furniture, grab the flashlight and batteries. The whole time I was living there, a hurricane never hit. It would move to the east or west, but you never knew.”

Later, when she was living in New Orleans and Hurricane Camille was sweeping through the region, she remembers driving back to her hometown to check on her parents, who owned a beachfront motel. “There were walls of debris on either side of us—furniture, road signs, parts of buildings. What intrigued me was that the landscape was like a big abstract painting, with disparate color and movement. There were things you could recognize and things you couldn’t.”

Not too surprisingly, the power of nature and the imagery of disaster would inform the installations and paintings made during and after Roland received an MFA from the University of New Orleans in her early thirties. There was not much exposure to art, nor encouragement toward an art career, when she was growing up—“I wanted to go to Old Miss to be with my boyfriend and to study interior design, but my parents were very strict and said, ‘No way, you’re going to New Orleans to study with the nuns.’” She was fortunate to find one nun who had graduated from Yale with an art degree. Roland became an art major finished at St. Mary’s Dominican College in 1971, in what she describes as “the midst of great upheaval.” She had a small child and her then husband was drafted. To support herself, she did graphic design and taught art for five years in New Orleans inner-city high schools.

But the art impulse kicked in in a big way once she was pursuing an advanced degree, and she showed large ambitious projects at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans. One, an installation called Post Natural Selection, was all man-made building materials with fake natural patterns and a message that was becoming more and more timely: Even as we’re destroying nature, we glorify it in ersatz imitations. “There were tiles that mimicked water, panels that showed fake rocks and woods, a fake-rock waterfall with real running water, Astroturf on the floor, and even a device that tweeted like a bird,” she recalls. “People didn’t quite know whether to laugh or cry. The secretaries in the building would have lunch on the Astroturf.”

In 1989, Roland moved west, and started teaching at the Institute for American Indian Arts (IAIA). The artist responded to the region’s particular vibes—what she describes on her website as “the proximity to big science, art, and spirituality.” Santa Fe is not far from Los Alamos, the birthplace of the first atomic bomb, and the Santa Fe Institute is renowned for theoretical research, including the development of chaos theory.

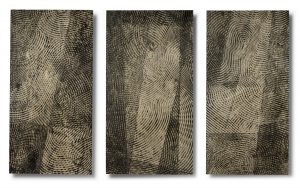

“Chaos is the science of surprise, and differs from predictable science, such as gravity, or chemical reaction,” Roland explains. “It is not really chaotic, but reveals patterns that form in what seems to be disorder. My work began to incorporate patterned mark-making and chance occurrence. The works manifest as fractals, systems, strange attractors, and the butterfly effect—all examples of chaos theory.

When the IAIA lost much of its federal funding in the mid-1990s and most of the teaching staff was laid off, Roland turned her energies to learning about the ancient medium of encaustic. She’d been introduced to the art of encaustic monotype printing by a colleague, Dorothy Furlong Gardner. “I was fascinated by its immediacy and the fact that it didn’t require a press,” she wrote in the newsletter for the Surface Design Association three years ago. “Instead, printmaking with encaustic (beeswax, damar resin and pigment) requires heat to melt the paint, so that it can be absorbed into the paper.”

At that point, Roland was riding a wave of renewed interest in encaustic, which coincided with the manufacture of ready-made mediums (before that you had to make your own, using pigments and binders). Artists like Joanne Mattera were publishing influential books on encaustic, and Roland herself began teaching workshops and even redesigned and manufactured the “Roland HOTbox™”—a box with light bulbs as a heat source, which is both insulated and lightweight. “The bulbs heat the plate without much electric draw,” she says. “When it heats up, you take encaustic in solid form. You can draw and paint with it, manipulate it, move the wax around. Then you put absorbent paper on top and gently press the back. The paper becomes the print.”

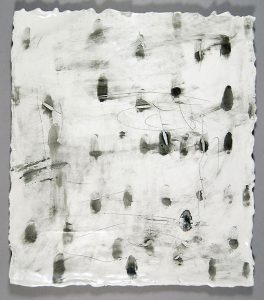

It’s difficult to have complete control over the process. “That’s the fun part,” says Roland. “It’s also the gift part.” She’s worked almost exclusively in encaustic for the last 20 years, exploring a wide range of abstract imagery, most recently making small-and large-scale monotypes and paintings that resemble imaginary maps. “My work changes as my interests change and as the world evolves,” she says. “It always relates to the natural world, ecology, and a spiritual connection. However, I’m at the point where I’m going to do what I want to do and then figure out how it fits into my life. Before, I would set out to make statements. Now it’s all much more relaxed and intuitive.”

Top: Photo of Paula Roland in her studio by Eric Swanson

Excellent work by a wonderful teacher. So happy to see this profile, thanks!

What an interesting interview about a very interesting & talented artist. I fell in love with encaustic monotypes when I took a week workshop from Paula. She is also a very generous teacher as well as a huge influence in the world of wax. Thank you for an excellent article!

Paula is a unique gem – articulate yet fluid – as is her work . Thank you for sharing her evolution and new images , her integrity raises the bar nicely for all of we image makers .

Ditto

Fantastic article on Paula! I appreciate knowing more of her history. Love her work! Thanks for this coverage!

I have been a fan of Paula’s work since I first met her in 2007. She is truly a master of her medium and continues to amaze me with her ability to push her work in new and beautiful directions. Thank you for doing an in depth article on her!

Thanks for this excellent article on Paula. I’m a big fan of both the woman and and her work. The wildness of nature she talks about definitely shows in her sensitive and powerful paintings. I’ve been fortunate to take several workshops with her and highly recommend her as a teacher.

I have long considered Paula Roland the diva of the encaustic monotype world. She is a truly wonderful person, giving and supportive to all around her. Thank you for bringing attention to this extremely talented artist.

So happy to see this article about Paula. I am a big fan of her work and of her as a teacher.

Congratulations on this article with its wonderful images of your artwork!

Thank you all for your comments. I am honored!

Professional article on a professional woman. Great standards of excellence for both. Let’s go imbibe at Josephs!

Nice! Hey, I’ve missed some of these – love “Wanderers Map””

Wonderful article, wonderful Artist! Does she have a website? Thanks for the article & pictures!

yes…www.paularoland.com

Love this wonderful article about an amazing artist and teacher. Paula has been an inspiration to me for many years since her time living in New Orleans!

Wonderful article! I’m glad to learn more about Paula Roland’s background. Thanks!

Beautiful, stunning work. Thank you for putting Paula Roland on my radar.

I’ve been a colleague, friend and fan of Paula’s for many years but in your insightful article, I learned many fascinating new things about her! Thank you.

I’ve taken a short workshop from Paula, purchased her hot boxes, and then later studied with Heidi. The combination of their approaches enriches my life. It is helpful to hear the projectory of a well lived arts focused life,

right up to how Paula is working more intuitively now.

Thank you for the article and visuals of her work.

Incredibly stunning work. I absolutely loved reading about your story, evoluntion and influences. Your work is captivating Paula!

Great article. Paula is an incredible artist and an amazing teacher. Life and her surroundings have become fuel for Paula’s work. Her portrayal of events and feelings is truly unique. I’m a fan of her as a person and an artist.

A wonderful article on Paula. I’m so happy I stumbled upon it. She is a great inspiration.

Great piece on Paula. This article gives me more insight into the genesis of her work. I’ve seen the changes and new pathways as they materialize in her work over time, and love that she says she is in a place that is “much more relaxed and intuitive.” Paula has been a kind and generous friend and a source of inspiration for me.

“However, I’m at the point where I’m going to do what I want to do and then figure out how it fits into my life. Before, I would set out to make statements. Now it’s all much more relaxed and intuitive.”

Į love this! Paula, you are my inspiration. I used to think I had to make statements with my work so I would be perceived as a serious artist ..I’m pretty much self taught. Now I go to my workspace and have fun, go with my gut and enjoy the outcome. My 4 yr old grandson has the right idea when he gets a brush or crayon in his hand…just go with it!