What Mokha Laget recalls best about her childhood in Algeria—and what has stayed with her throughout her career as an artist—is the quality of the light in North Africa. The daughter of a French diplomat, she spent the first six years of her life in the former colony of France and finds now that her home and studio outside Santa Fe, NM, afford a similar experience of golden Mediterranean light (they are at roughly the same latitude). “This is what you remember, this is what you gravitate toward and what you’re comfortable with,” she says during our conversation in the airplane hangar she uses for a showroom at the Santa Fe airport (her partner, a video artist, keeps a private plane there, and it’s a wonderfully spacious and accommodating venue for storing older work and displaying newer pieces).

If Laget’s intensely color-saturated canvases might indeed be said to reflect some of the geographic ambience of her childhood, they are also reminiscent of the mosaics she came across early in life and on later travels to North Africa. Something of those early systems of organization, seen in the ruins left from Islamic and Roman settlements, has stayed with her. “Islamic mosaics have a very rigid mathematical organization. There are geometries you can match to one another, even though the systems have been torn asunder in the ruins.”

But before she turned to abstraction, Laget was involved as a teenager with figurative art, and with making copies of the Old Masters at a studio in the south of France. “I spent a summer making rabbit-skin glue and working with plaster of Paris and learning traditional techniques,” she says. Her formal academic training, however, was in the U.S, and she earned a baccalaureate from the Lycée Français in New York, where she acquired a rigorous grounding in philosophy before moving on to the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C.

At the Corcoran, the artist had the good fortune to meet and work with Gene Davis, one of the members of the Washington Color School—along with Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, and Sam Gilliam—a group that was never precisely a school but, as Laget explains, “considered themselves part of a particular aesthetic.” Several members attracted the attention of influential New York critic Clement Greenberg and the rest, as they say, is art history.

Laget worked for three years as Davis’s studio assistant. “We had a lot of disagreements but it was always in good fun,” she recalls. “Every morning we’d have coffee for half an hour and we’d talk about everything—art history, music, food—and then we would get to work.” Most importantly, she says, from the years of working with Davis, she “learned early on what it is to be a professional artist. You have to show up for work. You have to be thinking all the time, learning as much as you can.”

Davis believed that an artist’s work should be recognizable from a speeding car, but Laget early on saw the problem with that: “It puts you on hold very quickly because it’s difficult to go out of those bounds.” It was a restriction the older artist suffered from throughout his career. “Any time he tried to do something that was not stripes, critics came down on him,” she notes.

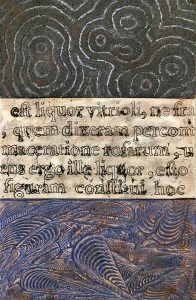

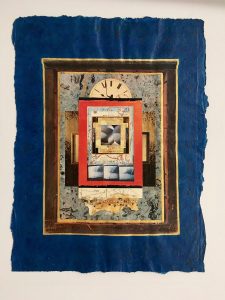

By the time she graduated from the Corcoran, the artist was making sufficiently sophisticated work to land shows in the D.C. area. “I was making hundreds of collages in what one critic called an ‘Esperanto of cultural remnants’”—there were passages reminiscent of Middle Eastern art, Arabic script, ancient mosaics, and other cultural relics—and, she says, “they sold like crazy.” Perhaps taking a cue from her mentor’s experiences, she realized that she was earning a reputation as a collagist “and that was not what I wanted to be known as my whole life. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed, and so I stopped when I was in my 20s.”

In the early 1990s, Laget worked as an independent curator and critic, writing about art for The New Art Examiner, a lively publication still very much dedicated to contemporary art. She also got involved in theater—as an actor, director, and set designer. Around the middle of the decade, however, it became clear that these activities weren’t going to provide a livelihood, and she began to think seriously about how to make money and still support her ambitions as an artist. Growing up in diplomatic circles, she’d gained some proficiency in several languages and so turned to earning a degree to become a simultaneous interpreter. After finishing the coursework at Georgetown University, which had one of the best programs in the country, she was hired on a contract basis by the State Department on the same day as her final exam. “My first job was six weeks with a group of French-speaking artists from all over Africa. We went to museums, spent time in artists’ studios. It’s a challenging skill but I really like it, and I’ve become good at it.” Gigs in the last couple of decades have been as mundane as interpreting for legal conferences and as exotic as working with the Coast Guard off the Horn of Africa.

On one of her early assignments, Laget discovered New Mexico. “I rented a car and went to as many places as I could because I wanted to buy land.” She found 20 acres on top of a mountain near Madrid, NM, and has been there ever since. “There was no well, no electricity, no road,” she recalls. “But I fell in love with the area. You can see five mountain ranges from my studio.”

About a decade ago, the artist turned to making shaped canvases and has been working steadily in that idiom, playing with perceptual ambiguities and often working on a nearly heroic scale—as long as 10 feet. (A work in progress for the Art in Embassies Program in Mauritania will be almost 400 inches wide when installation is complete this year.) “So much of the Washington Color School was about flat pictorial space, and that was the Greenberg effect,” she notes. Anyone who was working outside the canon suffered a certain opprobrium. “I always wondered what would have happened had these artists not been under this kind of tyranny. Color Field painting, according to Greenberg, cannot have dimensionality. But I started working with that idea—what if?”

Laget’s adventures with shaped canvases—generally realized in Flashe and pigment—often present optical puzzles, with shapes seeming to intersect and overlap and thrust outward into space, further teasing the eye with the shadows they cast, both real and illusory. Curiously, that fascination with light has its roots not just in the Mediterranean landscape of her childhood but also in visiting the monuments of a completely different tradition. “I spent a lot of time in Europe, looking at Gothic cathedrals, watching the way the light streamed through the stained glass,” she says. “It was a kind of epiphany.”

Though her work today may appear radically different from her earliest forays as an artist, Laget says she can see the connections. “I was always interested in systems of codification,” she says. “You can see that the geometry is always there.”

Ann Landi

Top: BOW (2017), acrylic, clay, and pigment on canvas, 39 by 78 inches

Excellent piece on an artist whose admirable work I know well. Such a pleasure to have anecdotes, quotes and insights free of art jargon. Thanks, Ann Landi

This is a wonderful piece and introduction to a new to me artist. And a fascinating story.

Loved this article, thanks for the introduction to Mokha’s works!

Ann – Thank you for introducing me to Mohka and her work. Wonderful article!