Self-portraits have always served artists in a variety of ways. Art historians have suggested that Jan van Eyck’s Man in a Red Turban (1433), with its inscription “Als ich kann”—meaning, “this is what I can do”—is both a self-portrait and a kind of calling card to potential patrons about the artist’s astonishing abilities. The same with Parmigianino’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524), painted at the age of 21 and presented as a gift to Pope Clement VII, a tour de force of Mannerism and a brilliant advertisement for the young painter’s gifts. As art gained ever more respectability, particularly among royal patrons, the artists themselves—like Rubens and van Eyck—often saw themselves as every bit the equals of their customers.

Closer to our own era and all its attendant anxieties and unbridled libidos, we have van Gogh documenting his own tortured visage and Picasso acting the part of the lusty Minotaur (regrettably we also get Jeff Koons in porn poses with his former wife). In our post-modern stew of possibilities, artists do not feel constrained to limit themselves to any particular medium or style, and so in this round-up we present self-portraiture in the realm of photography, paint, and sculpture, and interpretations that range from wildly expressionist to coolly analytic.

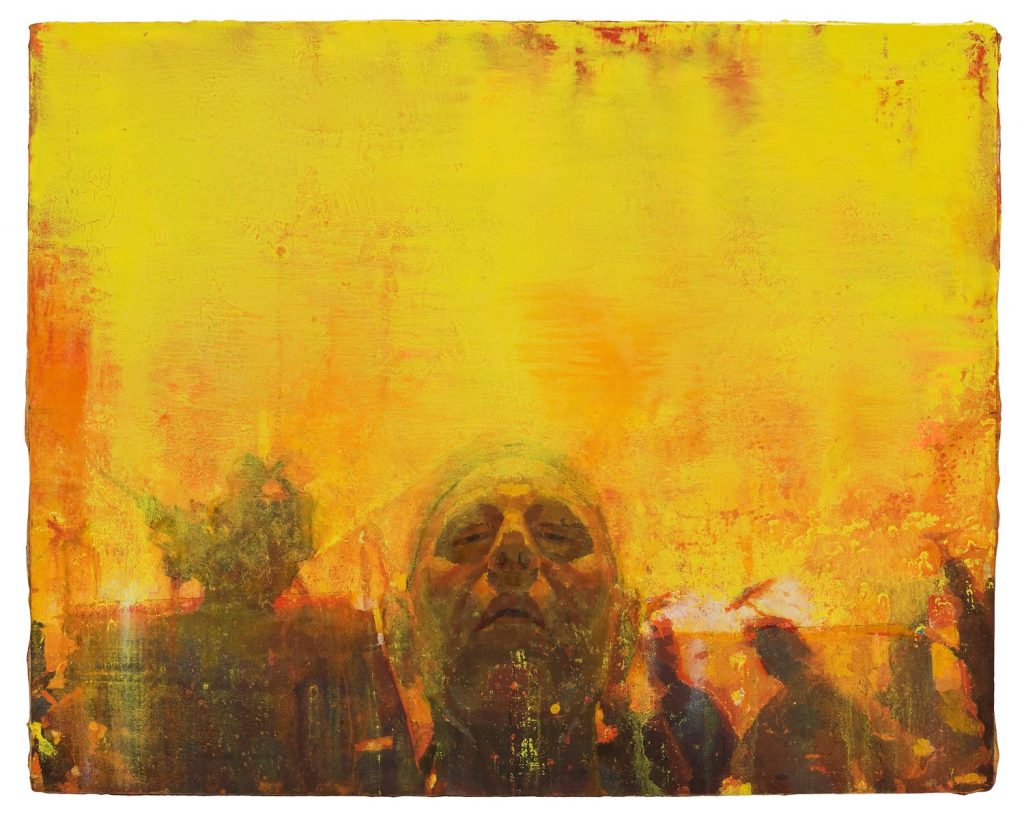

Susanna Coffey, Transport (2008)), oil on canvas, 15 by 11 inches. Transport, says Coffey, is part of a series of paintings begun in 2001 in response to U.S. interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Haiti, as well as the destruction of the World Trade Center.

In this painting, one can see a face (mine) in front of smaller figures and vehicles. In the background people wearing night-vision equipment, some carrying weapons, are enveloped in yellow haze. These ‘night soldiers,’ with their halo-like apparatus, reminded me of the angels from Masaccio’s Brancacci Chapel frescoes. I was struck by the vulnerability of these soldier/angels as they must negotiate night’s darkness to survive and do the work of their leaders, who sleep in luxury and safety. We can’t see what army they fight for; they are small in scale and like angels exist between life and death. The title Transport refers both to a vehicle and a state of dysphoria, of being moved along.

All my portraits are made from direct observation. Transport, like all my work, involved a gradual process. I stood before a large photomural in front of a mirror, and painted what I saw. While this central figure was made by my focus on my own reflection, it portrayed a self that suggested, as it arose out of the paint, a sense of a “we” rather than the “me.”

Patricia Moss-Vreeland, Self-Portrait (spanning several years), mixed media, 20 by 22 inches. I made this self-portrait as a collage of memories. Pieced together like a quilt, a metaphoric construction that I have used in some of my other works on memory, squares span off and around, overlap and are rendered differently. I decided to make myself larger in one location, much like the late Gothic, but moved the location to be off-center. One box contains a line from one of my poems about my mother, my early art mentor, and others hold references to past art projects, places, an earlier version of myself, and an image of my son jumping/falling into my life. I wanted it to be a stable structure therefore I use the grid, but I also wanted it to be pulsing with connections,that move you through an interlocking sequence of units, representative of how the past is woven into our present. It is how we accumulate experiences and information to make the connections to construct memory, a seemingly random or unified composition. I laid it out to create a kind of episode that I can build upon; episodic memory.

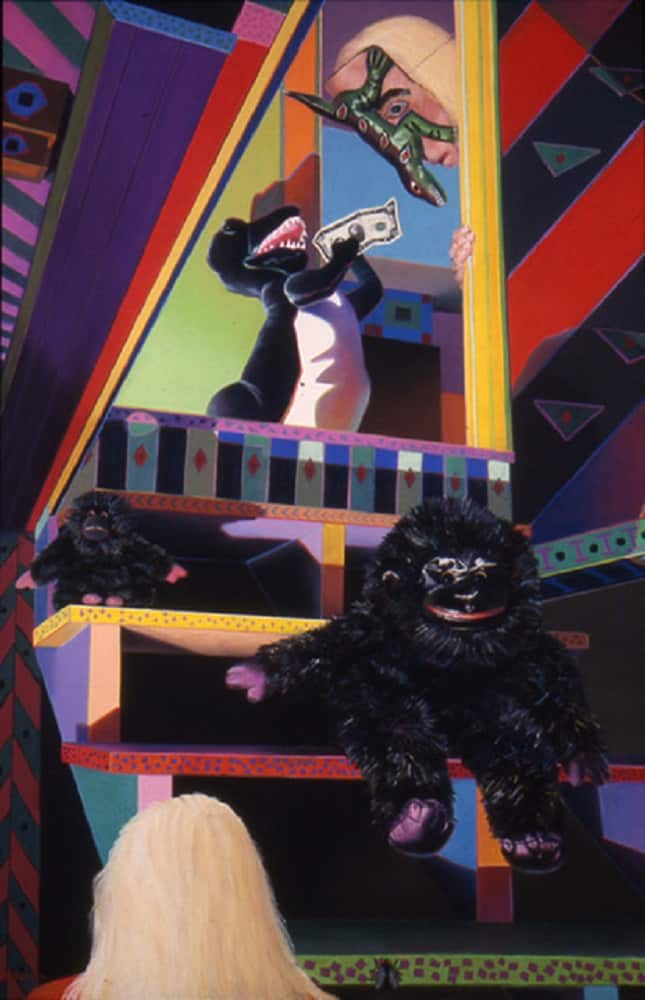

Barbara Rachko, Big Deal (1994), 58 by 38 inches. This is an early work from my “Domestic Threats” series of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings. In these works, my cast of characters enacts mysterious psychological dramas, with the various places I’ve lived serving as a backdrop. This painting happens to be in my house in Alexandria, VA, looking up from the basement to the main floor. It’s the one and only double self-portrait I have ever painted. Of course, that’s me at the bottom and top of the stairs. At the top I’m wearing one of my then-favorite masks made in Guerrero, Mexico and bought at Eugenio’s, a mask shop I still frequent in Mexico City. The other figures are stuffed animals that I was working with at the time, before I decided to focus exclusively on objects encountered during my travels to Mexico and beyond.

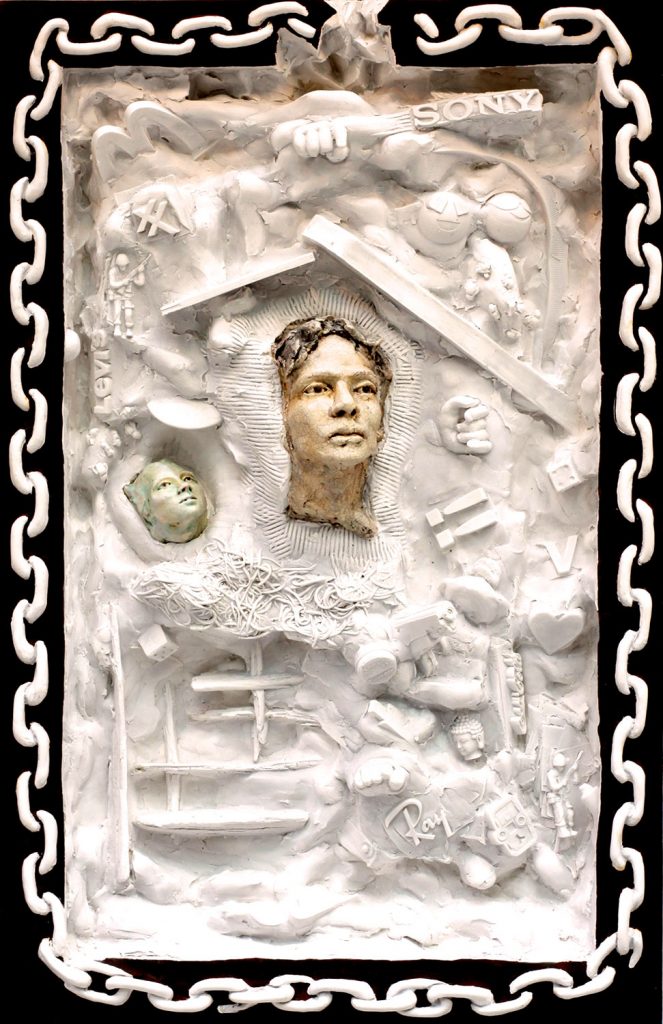

Bob Clyatt, Cscape #34, Self Portrait (2016), Hydrocal and Carrara marble, glazed stoneware, paint, 30 by 19 by 5 inches This piece, part of my “Cultural Landscape” series, places my glazed ceramic self in the context of some of the things that swirl around me and my awareness these days. The piece is a single-cast wall relief.

Jackie Skrzynski, Self Portrait Smiling (2016), pencil, 13.5 by 11 inches. I intend for the self-portrait to add meaning to whatever stage of life I am describing. I want to suggest the complexity of the experience of marriage, motherhood, or, in this case, aging. The profile’s horizontal orientation suggests landscape. The unusual placement, along with the exaggerated facial wrinkles, combine to transform a smiling face into something almost horrific.

Paul O’Connor: Self-Portrait (1987), scanned and digital print, shot on 35 mm film, 9 by 11 inches. I have very few self-portraits. One of the attractions to being a photographer is being behind the lens, not in front of it! I had to dig all the way back to my very first photography class I took at Pepperdine University to find this one, taken 30 years ago. I had been working with a contractor in Malibu for several years, and while remodeling a home on the famous Colony Beach came upon a mummified cat hidden inside a wall that we were tearing down. I kept that cat for several years, and it was one of the best cats I ever had. So when the assignment came up to do a self-portrait I had this vision to make this image out in the Mojave Desert. I’ve always had a deep fascination and connection to deserts which oddly enough reminds me of being out at sea. The sensation of infinite space, freedom from the known and lightness of being. Maybe that’s why I wanted to be hovering off the ground with my dead cat—somewhere between life and death.

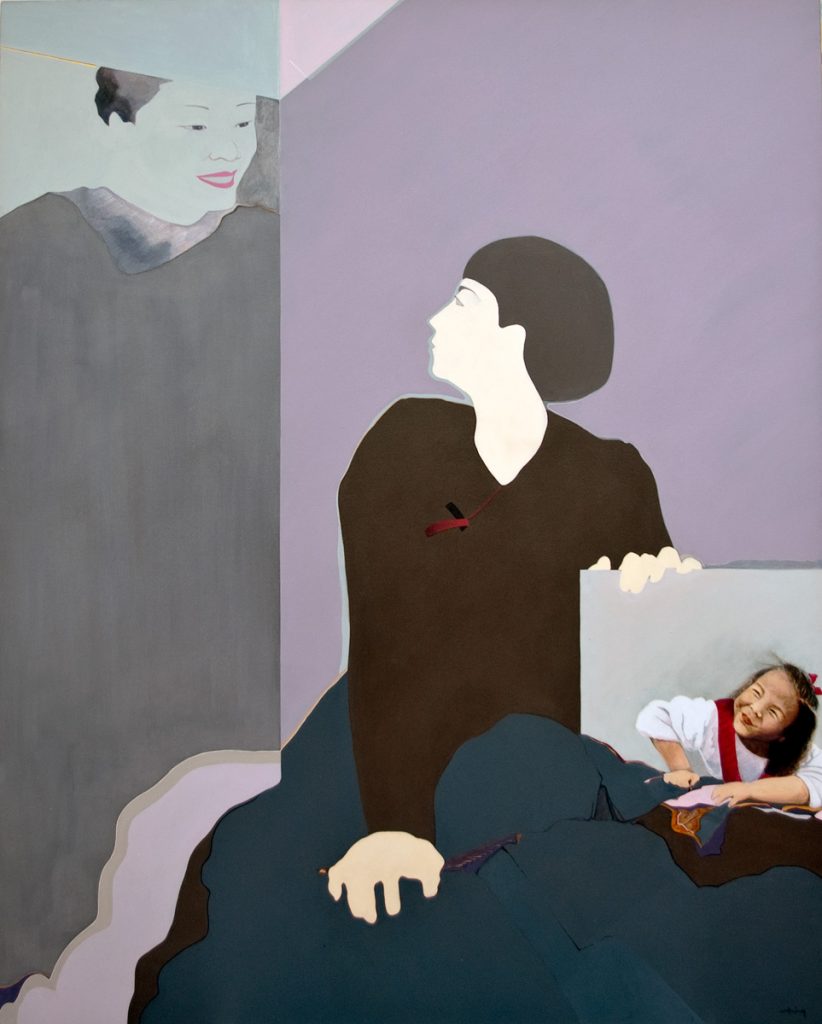

Mimi Chen Ting: Conversation: Mother, Me and Myself (1986), acrylic on canvas, 61 by 49 inches. My 96-year-old mother passed away last October. This painting, comprising a portrait of my mother, me as an adult, and myself as a precocious two year-old, was done at a time in my life when I really wanted my mother to know me–we had not had an easy relationship. I was fortunate to have been able to be at her bedside in the last two weeks of her life, and in the end I came to realize that what she knew of me was enough for her.

Brenda Goodman: Self-Portrait 5 In the Studio (2004), oil on paper, 16 by 14 inches. From 2004 to 2007 I did a series of self-portraits. I was very overweight and all of the paintings were me in my studio nude. This piece was the only one I did with my clothes on, though in the background is a partial view of me and my partner, Linda, in the nude. After losing 70 pounds, I no longer have a desire to paint myself!

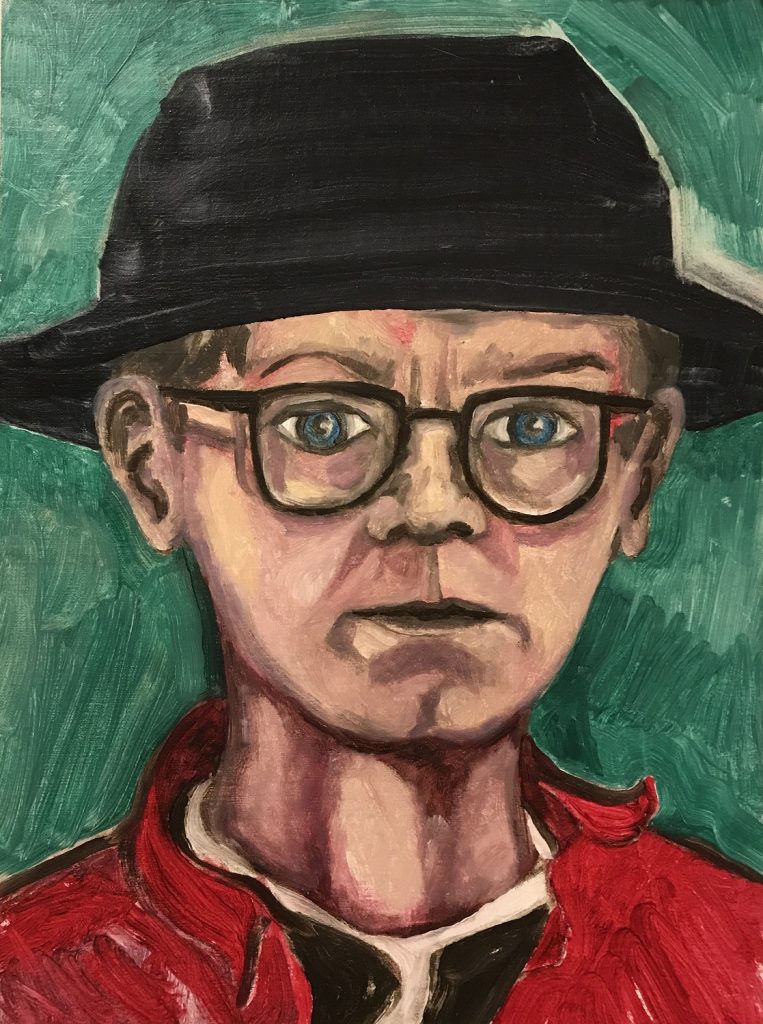

Kathy Cantwell: Self-Portrait (2013), oil on linen panel, 12 by 9 inches. It ends up that this painting was done during a manic episode (I’m bipolar) that went on for months, during which time I had this affinity for this hat and wore it every day, all day long as if I were Bolivian! I could not stop wearing it until finally modern medicine brought me back to a level playing field and I ditched the hat. It was a wild time and I laugh about seeing this painting now because I’m in complete remission and it’s as if someone else seized my soul and became obsessed with that pork pie hat.

Detlef Aderhold, Indianerhäuptling (2008), mixed media (acrylic, lacquer, and coffee) on canvas, 39 by 31.5 inches. In 2008 I was at a difficult point in my life. When I painted Indianerhäuptling, it was my intention to get in touch with my feelings and find a way to get a better understanding of what really was important for me. So I felt the need for a rapid, dynamic, largely unrestrained and spontaneous handling of paint and canvas. This process evoked special childhood memories: playing cowboys and Indians with my friends, often climbing the old elder tree in our small garden, or spending time on the bank of the Lesum River where shimmering reeds swayed on the wind. And then remembering my late father, this feeling of togetherness, when I was a small boy and he was telling me stories he invented about the life of the Indians, their adventures and their bravery. More and more it became obvious to me that this painting was about me and had developed into a self-portrait.

Top: Parmigianino, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524), oil on poplar wood, 9.6 inches diameter

Thanks Ann,

I’m honored to be in this amazing site!

XOX

Thanks Ann for including me in this profile of self-portraits. I have done my fair share of commissioned portraits during my professional life, but taking the time to look and consider oneself from this vantage point, and then to render it, I find most revealing. That you have chosen to give access to view other artists interpretations of themselves is so interesting. I appreciate that your selections honor this quality of artistic insight.