From her mother’s side of the family, Mary Zeran inherited a deep love and respect for crafts of all kinds—from Norwegian rosemaling to metalsmithing to textiles and embroidering. “My mom was always making furniture and boxes, and even carved wooden Santas. I wasn’t raised to see the difference between art and crafts,” she recalls. “I would watch her paint and at the end of the evening she would ask me to critique her work. All through middle school and high school, this was a daily thing.” Her grandmother, an art therapist, also did woodcarving and metalsmithing and Zeran recalls, “Grandma would go on vacation with us and show us how to do knitting and sewing in the car.”

Before the age of eight, her family had moved often for her father’s training and internships as an opthamologist—to Des Moines, IA, Alexandria, VA, Rochester, MN, and finally to Burlington, IA, where Zeran’s first love in school was music and she set her sights on becoming a concert oboeist. Then at the age of 18 she got a Rotary scholarship to live in Sweden for a year, and trips to galleries and museums began to nudge her in another direction. She recalls, in particular, a Chagall retrospective in Stockholm that “blew me out of the water.”

Nonetheless she went off to the University of Iowa with the idea of becoming a lawyer and then switched to journalism. When it came time to declare a minor, Zeran chose art and signed up for metalsmithing. (“I was one of the first girls to take shop class in middle school,” she notes, “and it was there that I realized I was good with my hands.”) She remembers the first piece she made in college, a “weird abstract wind chime” and on the walk back to her dorm room, she started thinking “’Wow. I’m an artist!’ I got the shivers, but kept that notion in the closet for about a year.”

She switched eventually to art, but the focus when she went to grad school at the University of Iowa was still metalsmithing, at which she was sufficiently accomplished that the Metropolitan Museum of Art accepted a set of her silver flatware that looked, she says, “like abstracted farm tools” (a well-connected professor helped her find a way into the collection).

But a series of unfortunate physical mishaps plagued her budding career in metals. Zeran came down with bronchitis and pneumonia one summer, which made her more susceptible to lung infections and internal damage from the acids she worked with. “I had to figure out how to make things without soldering, and so I worked a lot with wood and found objects.” Then just as she was developing ways to avoid soldering, she got tendonitis in her wrists. “I suffered two major injuries within a period of three years and that shut down the metalsmithing.”

Discouraged about the prospects for teaching (in 1991, “there were about 500 applicants for every position,” she says), Zeran and the man who later became her husband, Jeff Schipper, eventually settled in Seattle at what she calls “the tail end of the grunge market.” While working as a guard for the Seattle Art Museum, she became part of an artists’ co-operative and made several installations that centered around her grandmother’s life and pursuits, using materials like medical sponges, playing cards and a card table, and Harlequin romances.

And then came four years when she didn’t make art and worked full-time selling fabrics to interior designers. Yet “sorting through all that pattern and color, working with texture” would later inform her works in Dura-Lar and Mylar. As their parents were growing older, she and her husband decided 12 years ago to move back to Iowa, specifically to Cedar Rapids, where Schipper found a Craftsman-style house in an old neighborhood and Zeran went to work as a display person in a local department store. “Two years into that job is when I started painting,” she says. “The store needed paintings for different displays, little abstract works to make them feel homey and chi-chi. And then they down-sized me and I had all this free time.” Her husband asked, “Well, what will you do now?” And Zeran announced, “I’m going to become an artist.”

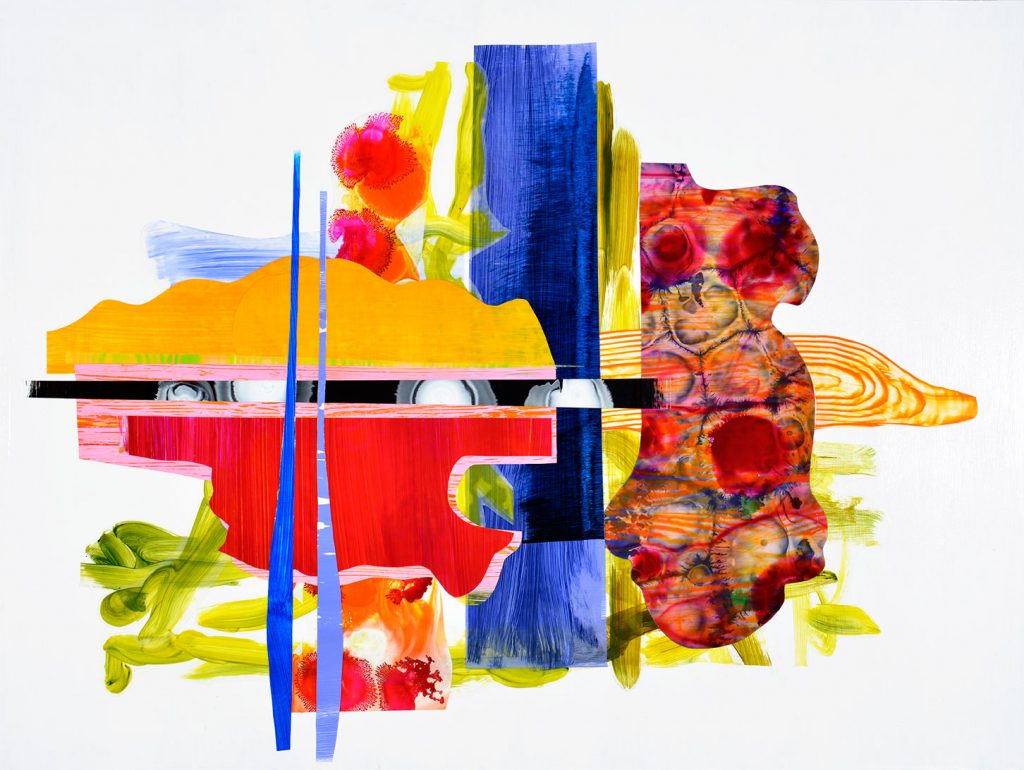

A “big fan of painting on paper,” she noticed that Katy Stone, an artist she admired in Seattle, often worked with Dura-Lar and discovered that “you can collaborate with the material in a way I’d never been able to do—it’s so spontaneous. You have to let the paint go and do its thing.” In the last few years Zeran has worked up a repertoire in that material (and in Mylar) that is astonishing for someone who has found her voice only recently. And yet she brings to her work a lifetime of experience in other realms: combining different elements as a metalsmith and installation artist, working with fabrics when she sold to interior decorators, and even the embroidery and other crafts of her childhood. The material was also “a way for me to work with found objects,” she says.

Though her approach is buoyant and spontaneous, the final works are weeks and months in the making as individual Dura-Lar sheets need to set before they can be arranged on racks, and her “secret recipe” for glazes can take a month to dry. In the end there’s a fair amount of depth to the paintings, but that’s hard to discern in reproductions (you can see it to some extent here in the installation shot at Kirkwood Community College).

“My life has had a fair amount of physical setbacks and disappointments,” Zeran says. “The way I’ve learned to fight sadness is to think about color. I just makes me joyful, and I want the last half of my life to be about joy and happiness.”

Ann Landi

Top: Between the Worlds (2015), acrylic on Dura-Lar on cradled panel, 36 by 48 by 2 inches

Thank you Ann for writing such a wonderful article. I’m thrilled!!!

Lovely work and nice to hear her story, I once worked as a department store display person in San Francisco. Thank you Ann for making us aware of artists we likely would never hear about anywhere else. xoxo

Thank you Annie Coe. I bet we could swap crazy stories about our retail experience!

Wonderful article! Even I learned something new.