Marina Cappelletto

Marina Cappelletto’s haunted spaces are bound to remind you of moments in earlier art. De Chirico’s mysterious piazzas with their ominous shadows and abruptly receding arcades. Magritte’s strangely misplaced patches of sky and water. Even Giacometti’s eerie skeletal Palace at 4 a.m. But Cappelletto’s visions are gentler and dreamier, although she would be the first to tell you her paintings and animations have nothing at all to do with her nocturnal imaginings.

They do, however, hark back to her early childhood and her memories of Italy. Until the age of eight, she lived in Milan. Her father, she says, “had a string of failed businesses, so I always had lots of letterhead to use for drawings, and my aunt painted as a hobby and let me work in oils when I went to her house.” But the most powerful influences were the buildings she saw all around her—the Duomo, the architecture of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the imposing 15th-century Castello Sforzesco.

All that changed when her parents divorced and she went with her mother to the U.S., first living in suburban Port Washington on Long Island, and then moving to New York when she was 14. By then Cappelletto knew she wanted to be a painter and enrolled in the High School of Music and Art. Her mother, who spoke five languages and worked as a bilingual secretary, worried about her daughter’s future ability to support herself as an artist but was also grudgingly supportive. “I remember going to a Picasso retrospective, I’m not sure what year it was,” she says, “and my mom looked at one of the works from his Blue Period and said, ‘You could have done this.’”

After graduating from Brown University, Cappelletto entered the MFA program at Columbia. There were few role models there for women in the mid-1970s, but Cappelletto remembers Jenny Snider from the undergraduate faculty as an important mentor who taught her “always to think about what would come next in my work.” Through the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs she also took part in a work-study program that placed students in the studios of artists who had received grants from the state. She worked first as an assistant to Joyce Kozloff, who introduced Cappelletto to her circle of colleagues, including Valerie Jaudon, Howardena Pindell, Miriam Schapiro, and Ida Applebroog. “Whatever role models were missing from my grad-school education, the artists I met through Joyce and later Marcia Hafif more than made up for the lack,” she says.

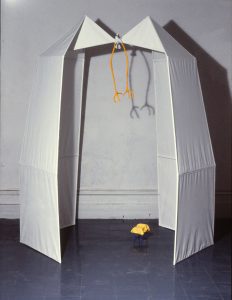

After getting an MFA, Cappelletto entered the two-year studio program at PS 1 in Queens. Her works from that time were mostly paintings and a continuation of diorama-like constructions she had made as a grad student. The first, Teresina, was named for her grandmother and featured a tent-like structure and a tiny bed. At the top is perched a screechy bird with impossibly long yellow legs that cast ominous shadows against a wall. “The bird represents my grandmother,” she says. “I thought if I remembered her bed as having a bird on it, it must have something to do with her. She was both scary and protective in my memory of her.”

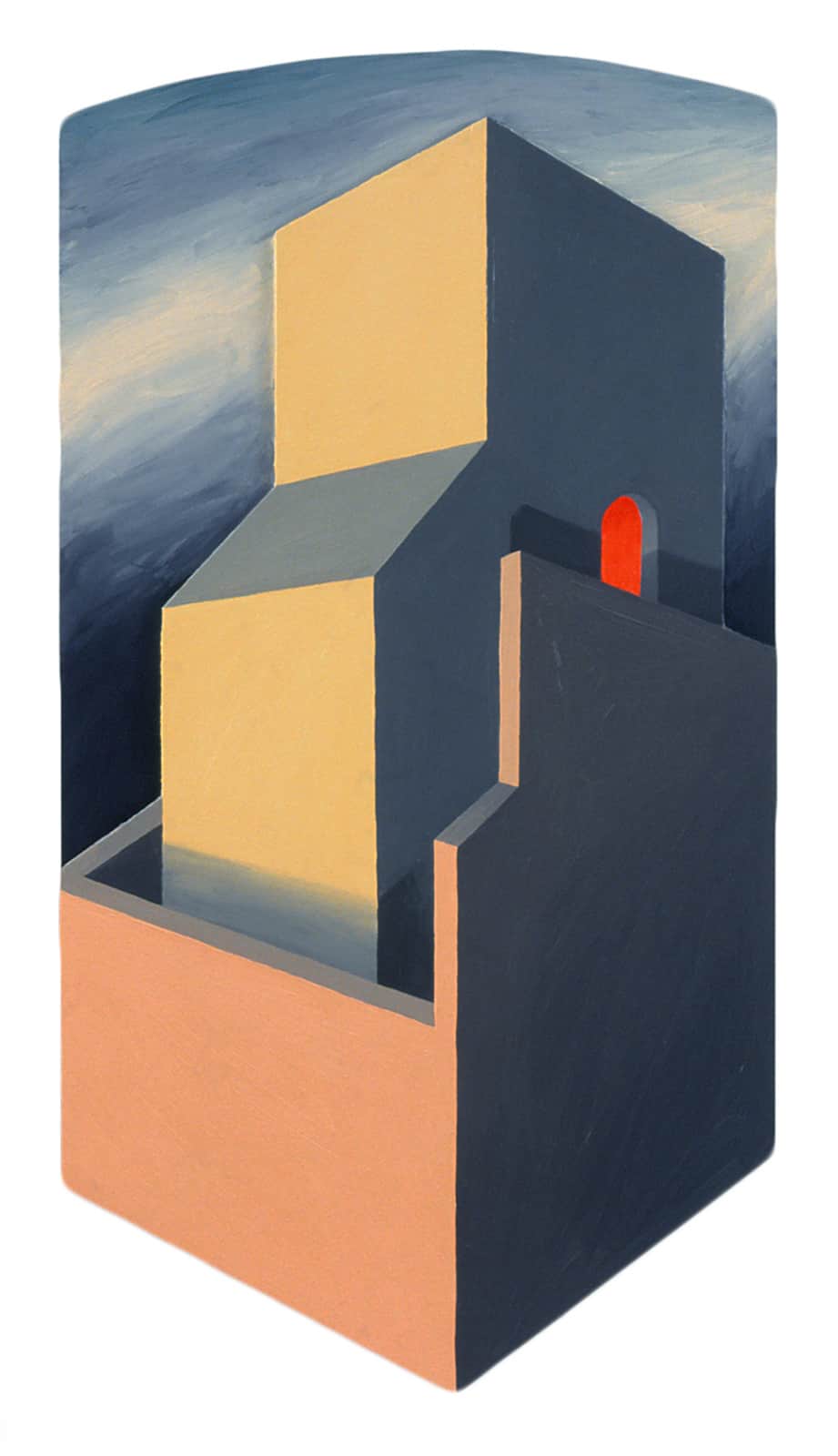

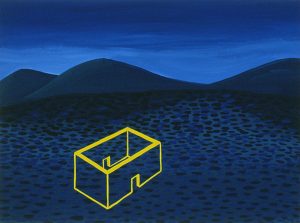

By the early ‘80s, Cappelletto was showing with Pam Adler Gallery, first on West 57th Street and later in SoHo—oil on plywood paintings of empty structures, sometimes maze-like, set in vacant landscapes or against conical mountains. Arched Gothic windows and doors and hulking castles may recall the architecture of the artist’s girlhood, but the works do not invite literal interpretation. During that period, she also had two solo shows with Wessel O’Connor Gallery, first in Tribeca and later in Soho.

“Architecture was important to me,” she says, “because it was something I could recall. It was historical. I didn’t really feel that here.” Travels through Italy—first to the hill towns of Tuscany and Umbria following graduation from Columbia, then in 1988, a year in Venice—underpinned an iconography based on the colors and structures of earlier times. Anyone who has visited La Serenissima may recognize in Cappelletto’s works the irregular shapes of the squares and piazzas that punctuate the city. The artist also spent a fair amount of time visiting the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, where Giotto’s frescoes of the life of Christ may have reinforced a predilection toward dramatic simplified shapes. Her colors, she says, come from Medieval and Renaissance painting. “I think I always had a longing for the country where I was born.”

In 1992, Cappelletto went to Paris for a residency given by the Cité Internationale des Arts, funding her travels in part with a Pollock-Krasner grant, and stayed until ’96. “Part of my interest in spending time in Europe was to be able to see more historical work in depth,” she says. “In Paris, I got the chance to study illuminated manuscripts, and throughout France I visited Romanesque churches to look at the architecture and sculpture.” Occasionally autobiographical notes will creep into her paintings, as when she introduced dark curtains to the edges of the painting, disclosing only a small slice of landscape, during a period when she was suffering from depression: the width of the curtains indicated the intensity of the gloom.

To support herself, Cappelletto teaches Italian and evaluates young children for developmental delays. She lives in a three-story building she has owned for four decades in rapidly gentrifying Williamsburg, Brooklyn, devoting one floor to a pair of studios; one is used for painting and another is “where I do everything else.” In the last decade she’s produced a series of animations that are like virtual tours of her imaginary landscapes. These have an enchanting, strangely meditative quality—like clips from a dream, though, like her paintings, they are not anyone’s dreams in particular.

If Cappelletto’s imagery has not changed radically over the years, it holds fast to a metaphysical space de Chirico regrettably abandoned as he matured and Magritte never fully developed in favor of visual one-liners. Her paintings are testaments to the enduring power of memory and the transformative nature of art.

Ann Landi

I Thank you for highlighting Marina Cappelletto’s work. I love “Teresina”, which I had never seen before.

Thank you for this wonderful essay. It is so well written and informative. Loved seeing these paintings, they are a slow read, carefully worked, but surprising. A mystery that lingers.

Thank you, Ann, for a really thoughtful essay on Marina’s life and work. In its “simplicity” the work has a magical meditative power which (as you mentioned) feels very much as if one is in the midst of a softly unfolding dream.

Under The Radar pieces are always a favorite. Feels like a privilege to go behind the scenes with other artists. Thank you!

Wonderful in depth essay. Beautiful engaging work. Thank you.

great insights into such a great artist!

I greatly appreciate this brief but in depth essay on Marina Cappelletto’s work. I have always admired it and appreciate it even more now with this additional back ground information.