A dedicated teacher looks back on three decades in the classroom

In December of this year, I will retire from teaching painting, a job I’ve loved for 30 years. Although I am looking forward to a new phase in my life, I will miss this role. I’ve had a good run and feel extraordinarily lucky to have spent the bulk of my adult life in the classroom. Most of all, I will miss my students: their smiling faces, their energy and enthusiasm, the diversity of their lives and concerns, seeing their work grow and flourish. They have challenged and changed me and have opened my eyes. It has been such a privilege to know them.

I am leaving, however, with a heavy heart. The world is not the same place it was when I first started my job, let alone when I started my own art education. For art education—really for all of the arts and humanities—there is a profound crisis of identity brewing and it leaves me wondering what the future holds.

When I first moved to take my teaching position at a small, isolated state university on the Northern California coast, it was for a temporary, one-year appointment. “Be careful,” one of my older colleagues warned, “this place has a way of growing on you.” And he was right; the one-year post was extended for another three years and before I knew it, 30 years had flown by.

I never imagined that I would live in the country. I thought of myself, romantically, as a confirmed city dweller, and I loved being close to all of the exciting cultural amenities that an urban art center offers. But even 30 years ago, San Francisco, with its rising rents, was showing signs of becoming a hostile place for artists, the very people who had helped shape the city’s reputation as a progressive and creative community. Even before the ensuing dot.com boom of the 1990s, the handwriting was on the wall and I realized pretty quickly that my future prospects were limited. So, despite the entreaties of my friends, who cautioned me that by moving I would be sacrificing my professional career as an artist, I took the job and moved north. And I felt really lucky.

And for a time, the dire predictions of my friends were correct. When I first moved upstate, the internet didn’t exist, there was no Instagram, no websites. To document your work and promote yourself meant making slides, a laborious and expensive process that took weeks. To be in a show or put my work in front of a curator, I had to drive for hours. Sometimes, I felt that I was marooned on a desert island. But, oddly enough, it was also nice to be out of the mix for a while.

One thing I often mention to students, is that becoming a teacher made me a better artist. I learned to take the critical eye I used on my students’ work and direct it to my own. And the stability that a steady paycheck brought, after years of stringing together different gigs, was a godsend. But teaching tends to be a largely one-way conversation and often, after so much giving, you are left depleted and exhausted, with no energy left for yourself or your work. If you are one of the thousands who work at a teaching university or a high school and not an elite research institution, then your teaching load, which includes academic “service,” is heavy and there is little support or time for pursuing or marketing your creative endeavors. Added to this load are other life expectations that need attention: motherhood, your relationship with your significant other, aging parents. Your work suffers and you devise ways to find the time to make it—perhaps by getting up very early or staying up very late. Nevertheless, I persisted.

Technology has profoundly changed much of this—mostly mostly for the better. It is now possible to conduct a career as an exhibiting artist no matter where you are, and social media easily connects you to the world. As a teacher, I can access the work of anyone anywhere on the globe and instantly show it to students. This has allowed me to diversify my curriculum in ways I never thought possible. And technology has made things easier in a thousand different ways—learning management systems, Google, digital projectors, streaming, cell phones, Zoom lectures.

So why do I feel such trepidation? Hasn’t the Internet made things easier, more egalitarian? For one, I worry that the cost of education has vastly outstripped the student’s ability to pay. I worry that they are leaving school under such a heavy debt burden that they will never be able to make art. Where once I might have encouraged my best and brightest to go to graduate school, I seldom do anymore because I am worried that they will be stuck, that there will be no jobs for them at the end and they will be left with nothing but a pile of debt. And I worry about all the bright, promising students who, for lack of money and opportunity, will abandon their hope of being an artist, depriving the world of what they might have contributed. Will the art world that is left exist only for those who have the economic and social advantages others don’t? Or has this always been the case?

Beyond these practical, financial matters, there are also the problems I see that go to the very soul of arts education. Educational institutions, in this era of risk management, are no longer conducive to the experimental energy so necessary for young artists. Measurable learning outcomes, designed for assessment, dominate the curriculum. No longer can an instructor meander creatively as John Baldessari did, making things up as you go along. If we are requiring students to understand exactly what they are learning, where is the challenge for them and where is the mystery? Where is the inspiration? If we hold them so close to a strict line, how do we teach young artists the necessity of taking risks, courting failure and working outside their comfort zone? Increasingly, universities market themselves by referring to the employment statistics associated with particular majors. Where does that leave art—or literature, philosophy, and history for that matter? Does an arts education, in the context of a public university, even make sense anymore?

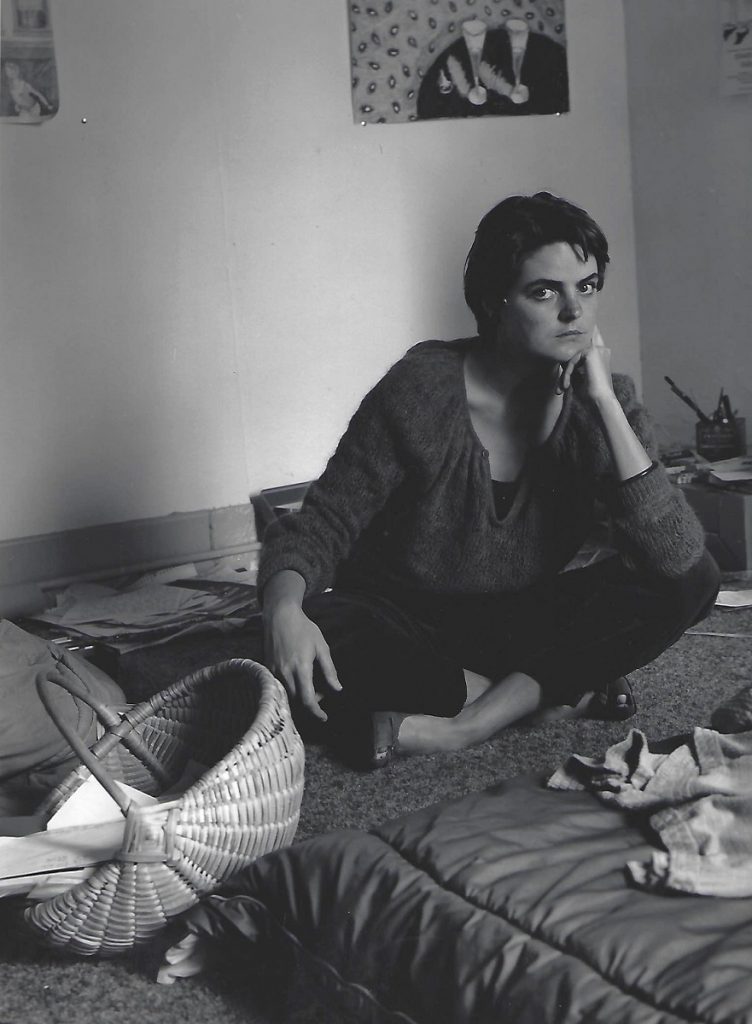

I think of myself at 18: an inexperienced middle-class girl, working to pay her way through college, stumbling upon a painting class and finding enchantment. Somehow, I managed to make the audacious decision to become an artist, even though being a woman made that a fairly dubious proposition. But I had advantages that my students don’t have–namely, my education was extremely affordable, enough so that I could work my way through without incurring debt. And there was little talk in those days of learning to be a “professional” artist because it was pretty evident that almost no one in the art world was making a lot of money and you accepted that. What you were taught was more inspirational than aspirational– you were learning to be a thinker and in doing so, you were committing yourself to a life lived creatively and outside of the norms set by others.

But in this world, is that now a laughable premise, its roots located deeply within white privilege? With the cost of education, the cost of art supplies, the cost of studio rentals, the lack of health insurance – how can a student commit to a life as an artist without some guarantee of income or promise of success? The stakes are now too high, the reality too impossible.

If anything, this global pandemic has taught us that the arts are important and essential to our happiness. Humans have an innate desire to create, to use their hands, their words, their instruments to create something not just because they need to make money but because they simply need to and because they want to share what they did with others, and that sharing brings pleasure to both the maker and the viewer. Somehow in the past 20 years or so, the glamour and money in the art world have perhaps twisted that impulse toward another goal. We are told to be professional, to meet the right people, to follow a certain set of guidelines to ensure success, to attend the right MFA program.

Perhaps my fears will be allayed in what Jerry Saltz refers to as the “new artworld”. Perhaps the pandemic will be a great leveler. There are already signs that there is a new energy in the digital world—exhibitions, blogs, online publications. The Black Lives Matter movement is making changes in cultural institutions that I hope will be lasting. Will expensive art schools survive? I’m not sure. Will galleries survive? Will the art fairs be a thing of the past? Will people from all sorts of backgrounds and experiences continue to make art and will it be valued not for its investment value but for its ideas?

I’ll be looking into my students’ eyes this semester from the distance required by my computer screen, and I will think about these things. My sincere hope is that they. too, will be able to live a life of creativity outside of what societal expectations are assumed for them. I hope that they, despite the obstacles in their path, will be able continue creating and enter what the philosopher Hannah Arendt referred to as “the life of the mind”.

Beautifully put, Teresa! I’m so glad I was a student in your first class and happy that we have stayed in touch. I love your work and very much appreciated you as a teacher!

Thanks Helen! Yes, you were there at the very beginning and it seems like yesterday!

This was so heartfelt and beautifully written. It expresses so many of the things I’ve felt and experienced both as an artist and a teacher. Art has never attracted the faint of heart and I truly believe artists and art will prevail, though will certainly be changed.

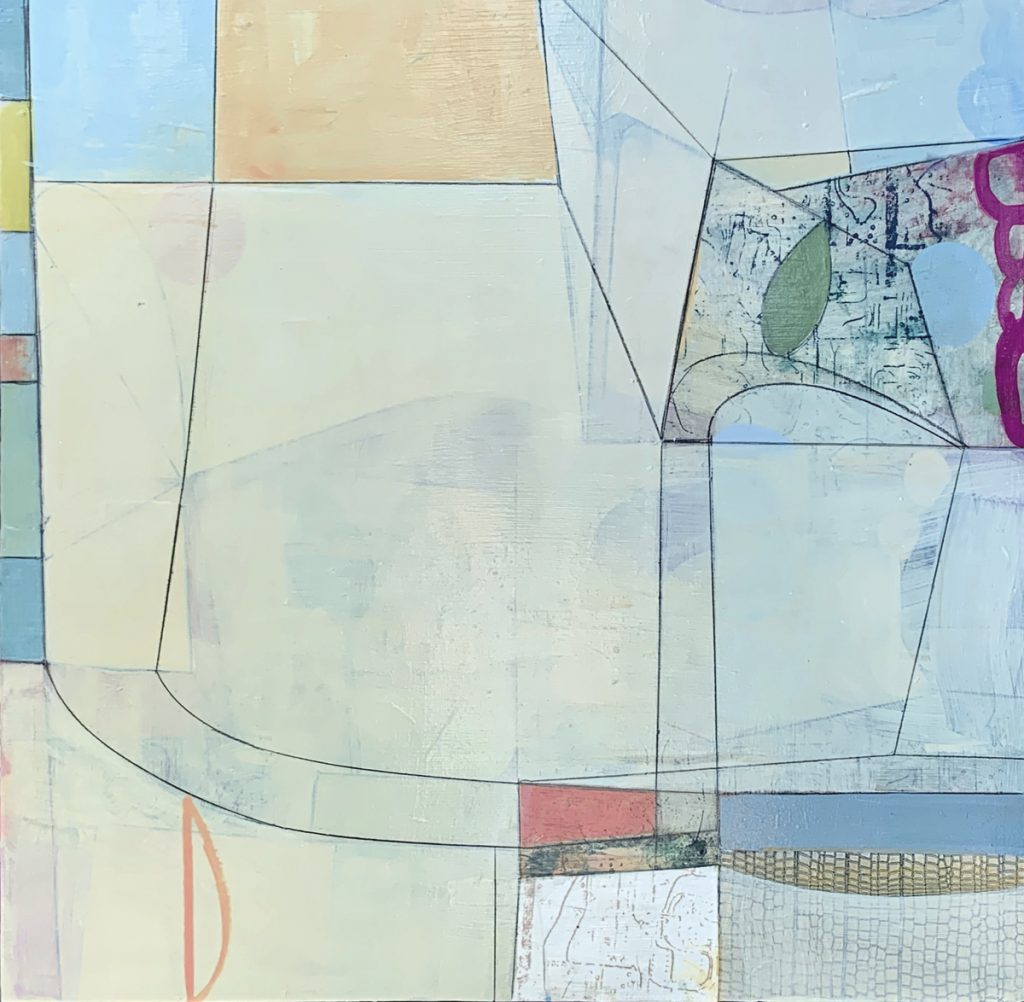

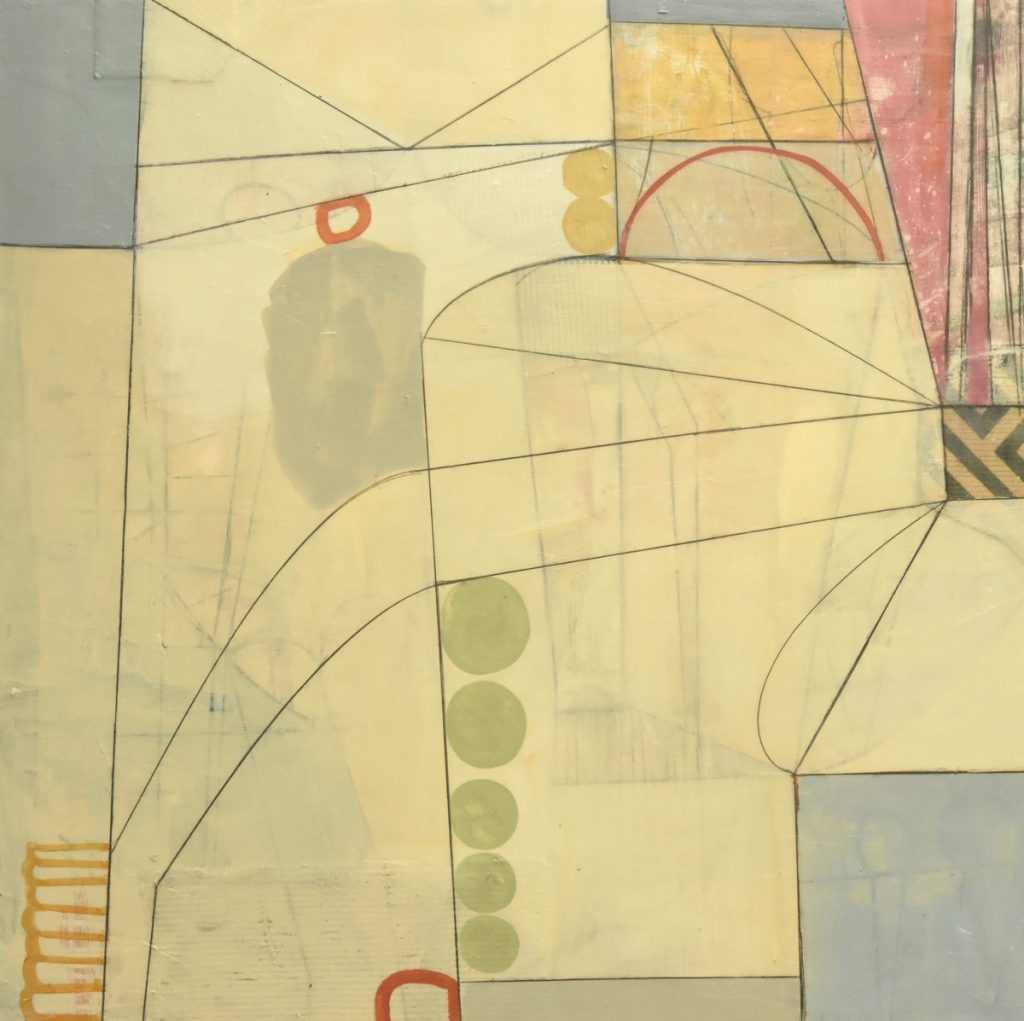

Your paintings were the perfect accompaniment to your words as they seem so delicately balanced and composed, though tension is obvious in every line. Bravo! And best of luck in the next new phase of your life.

Thank you!

I believe I would have benefited by being your student. I wish you for you happiness, serenity and much creative joy in your retirement.

Teresa, you were the best painting teacher I’ve ever had. You built a loving, safe and open environment that made our class feel like a 2nd family. Wonderful teachers like you inspire me to be an art educator. So that I can pass it on to the future generations. The debt, and an unhealthy amount of student loans, did defer my becoming a teacher sooner. I hear your concerns because they are exactly mine too. It took me 3 years after graduating to decide that I would take the plunge into teaching. Now that I am here, I still would encourage my fellow colleagues to go into art and education (especially my black and POC artists). But I do so with trepidation because it is definitely not the easy road. Sometimes, you need to fight the system from within.

So glad you are taking the plunge because schools need dedicated, inspired teachers like you!!!

Wonderfully well written article, Teresa! As a non-artist about 19 years into my own state university teaching career, many of your insights resonate deeply in me.

After 22 years teaching in the Art Department of a community college I know this story and the heartache of seeing students funneled out of the humanities and teaching constricted to fundamental courses. We need the humanities in this dark time more than ever. Thank you for your beautiful paintings.

Thank you Ann!

Such a great article, Teresa! You’re articulating many questions not just about art education but higher education in general. How can we fulfill the promise of higher education, if access is still so limited for some many of our potential students? It has been awesome to be your colleague – we are lucky to have had your energy, knowledge and enthusiasm.

Thank you Bori – I realize that what I said resonates with teachers outside of the arts – I probably should have noted that! Thanks for reading and for being such a great colleague!

A lucid and eloquent look at what it means to be a teacher, what we hold in our hearts for our students, and how we manage our own creativity alongside and among that of our students. Thanks Teresa for taking the time to write this reflection during your final semester at HSU. I understand well how bittersweet the separation will be. Whether or not you are in front of a class of students, though, your past students will carry with them your inspiration, your thoughtfulness, your empathy and concern, your keen awareness of what’s going on in the world, and your savvy insights. And the rest of us who know you or who meet you, will feel privileged to gain from our acquaintance. You model for all of us how to balance the sometimes-horrendous outer world we feel responsible to with the calm and objectivity of our inner creative callings.

Thank you Emily! I appreciate your kind words.

I too have just retired after 30 years of full-time college art teaching. Everything you wrote has rung a bell with me. I’m leaving the teaching field (can you ever stop being an art teacher?) with some very mixed feelings. I’ve watched creative, motivated students lose their way because of the cost of their education, or the unrealistic rigors of the new world of assessable learning outcomes. Over 30 years I’ve also seen students getting less adventurous and less curious as they are sucked more and more into the digital flatland of screens. I’ve had countless arguments with administrators (and fellow faculty) about the continual need for face-to-face instruction with hands-on problem-solving challenges, and less remote, digital instruction. The world is changing and it gets harder and harder to understand what it is like to be a young creative individual growing up today. I’m hoping that the changes that will come about post-COVID will bring a renewed awareness of being human and being creative, with or without colleges and a commercial art scene.

Thank you Bori – I realize that what I said resonates with teachers outside of the arts – I probably should have noted that! Thanks for reading and for being such a great colleague!

Thank you Iain for your comments and congratulations on your own retirement. I appreciate that there is another teacher out there who feels much the same as I do. I started teaching (my final semester) this week and was struck by how many students asked me for “permission” to use certain materials, techniques etc. and I can only assume that this dutifulness comes from the rigidity that assessment places on course content. I also hope that in a post-COVID world there will be a greater appreciation for all of the arts.

Every word you wrote about education is true. As an adjunct, there is little reward any more as I scramble to make remote learning work, putting in far more time and effort than I’m paid for. It’s discouraging. I, too, have learned to take the critical eye I use on my students’ work and direct it to my work. It’s made me a better artist and a better teacher.