With his full beard and flowing corona of snow-white hair, Gendron Jensen looks a little like a poet from another century. Sometimes he sounds like one, too. “Nature is dispassionately nurturing at its heart,” he intones at one point during an interview. “I can reach out with my long arms and visually take it into my keeping.”

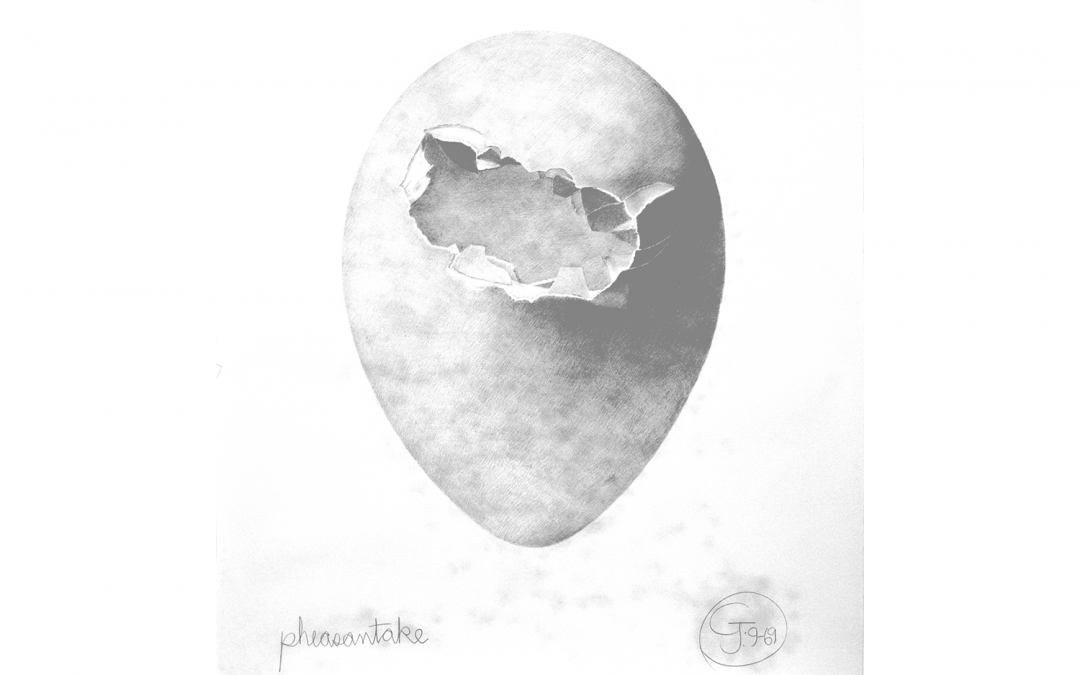

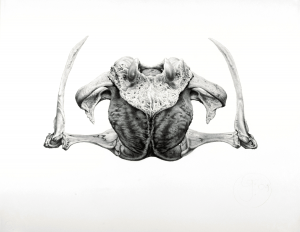

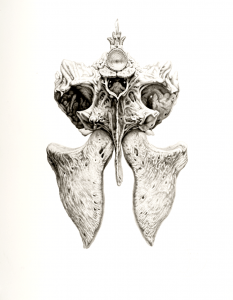

For the past 50-odd years, Jensen has focused exclusively on one of nature’s most evocative and yet easily overlooked relics: animal bones he’s found while hiking the north woods of Minnesota or the extensive lands near his adopted home outside Taos, NM. He works almost exclusively in graphite on sheets of paper as tall as seven feet, making meticulous renderings of the intricate infrastructures of wildlife, some of them road kill he’s come across in his wanderings. The drawings are so precise zoologists can identify them by species, but disembodied from their source that have a spooky, iconic presence, like the totems of some unknown tribe.

Jensen discovered his first bones at the age of six when he went exploring the hardwood forest in back of the family home. Wading in the reeds of a lake he found the skull of what was probably a red squirrel. “The upper teeth, the central incisors, curved back into the skull,” he recalls. “I was able to pull that crescent-like bone all the way out, and it touched me in a deep way.”

At the age of 19, the artist entered a monastery in southeastern Wisconsin but stopped short of taking his vows and enlisted in the navy. Following a nervous breakdown, he returned to the monastery and spent the next four years working in the print shop and living in the beekeeping house. When he was 26, he began drawing: “From the water to the land to the air, all of the creatures that roamed the wilderness in proximity to the abbey were at my disposal,” he says.

From 1970 to ’86, during what Jensen calls his “burning years,” he continued to live in the north woods, doing odd jobs, hauling garbage, building houses, or working in the grocery store. “I did grunt work so that I could keep my mind free to unfurl,” he recalls. “I slowly began more and more to draw all the time.” He established his first “bone room” in the family farmhouse in Grand Rapids, MN, and still keeps shelf upon shelf of bones in the studio he calls the “ossorium” in his home in Placita, NM.

In 1987, Jensen met Christine Taylor Patten, an artist in Santa Fe whose meticulously crafted crow-quill drawings in ink were singled out for high praise at the Istanbul Biennial three years ago (she has also contributed an essay to the site, and both she and Jensen have been featured in reports about drawing). Their courtship took place mostly via the mail, as they sent more than 100 letters back and forth, including pictures of works in progress. They were married in August of 1987.

Jensen had his first gallery show in Chicago in 1972 and has slowly begun to attract more attention with exhibitions in Albuquerque, Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., and Geneva. Throughout his career he has been encouraged by mentors like feminist art historian Griselda Pollock and Graham W. J. Beal, director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, who was chief curator of the Walker Art Center in the late 1970s and was attracted to Jensen’s work for its “fierce spirituality.”

Spring of 2010 marked his first New York show at Knoedler Galleries. Three years later, filmmaker Kristian Berg directed and produced “Poustinia” (from a word meaning “spiritual grounding”) about Jensen’s life and work. The half-hour documentary vividly captures the artist’s process and deeply spiritual connection with his subjects (“When I find them,” he says of the bones, “I feel this tingling in my hands.”) The film also offers an affecting glimpse into the collaboration between an artist and printmaker—in Jensen’s case, Tamarind Press in Albuquerque NM, with whom he’s worked on producing numerous lithographs.

Now 78, he looks on his early travails with a sense of equanimity. “At my age, I’ve been broken down by so much and sobered by so much,” he says, in typically elegiac language. “My winter of discontent has been a long one, but I’ve come into the bright morning, into this springful season.”

Ann Landi

top: pheasantake (1969), graphite on paper, 6 by 5 feet

I love his work, admired it for many years.

love this! and what a story he has!

Yes, I admired his work when you first published something on it Ann. And even more now with more background.

I love this article. Gendron will be so missed. Thank you for mentioning “Poustinia”. I feel so fortunate we were able to complete even a short film on Gendron’s life and work. If anyone cares to seek it out, the film is available on iTunes and DVD.

We are Saddened to hear about Gendron. He was an amazing artist, friend, and inspiration. Our thoughts are with Christine.

I own the secondary study of “Pheasantake” which, though smaller than the final version, is just as stunning. For Gendron’s graphite works he would usually do primary and secondary studies before launching into the epic sized final drawings.