Extreme Self-Marketing

This is not all about Jeff KoonsIt should probably come as no surprise that Jeff Koons at points in his career has hired “image consultants”—professionals who give advice on cultivating and presenting an appealing persona. The artist got his start, after all, as a commodities trader on Wall Street, and must have learned early on a thing or two about marketing. “He manicures his image and his press fastidiously,” says producer Henry Rosenthal, who helped edit a recent documentary about Koons, “Jeff, Embrace Your Past,” with filmmaker Roger Teich.

The couple of times I have seen Koons, on “Charlie Rose” and in a memorable segment of the late Robert Hughes’s landmark 1997 series, “American Visions,” he came across as a big overgrown kid, an ingratiating naïf with a voice as tender and waiflike as Michael Jackson’s. The one time I spoke to him, about eight years ago on the occasion of an ARTnews tribute to Robert Rauschenberg, the same childlike, space-cadet qualities came through loud and clear on the phone.

“In public appearances, Koons come across as a big overgrown kid, with a voice as tender and waiflike as Michael Jackson’s.”

How much of this is a put-on? How much a carefully groomed front, as cunningly crafted as those of old-time Hollywood movie stars? It’s probably impossible to say, though Rosenthal accused Koons of the “kind of paranoia and obsessive control issues that come with extreme celebrity.”

Koons’s marketing savvy seems part and parcel of the times, but what was truly surprising a couple of years ago, in the course of writing a story about a show of Cézanne’s still lifes, was to discover how the famous “hermit” of the Jas de Bouffan also constructed a kind of p.r. campaign for himself, or as much of a campaign as one could maintain in the late 19th century. As Benedict Leca, the curator of “The World Is an Apple” at the Philadelphia Museum in 2014, pointed out, “He wanted to paint himself as an untutored savage, a rough-hewn provençale, but he was exactly the opposite. He was systematically crafting this persona as intuitive and anti-cerebral, and he created a mythology about himself, which was false.” In our interview, Leca called this a “patent self-construction of an artistic identity” and added, “Cézanne wanted to be seen as outside the rules of his medium, as a kind of freakish genius who evades conventional interpretation, and yet he wanted very much to be recognized. It’s this weird kind of double game he was playing.”

In the annals of culture for the last 150 years, Koons and Cézanne could not be more different. But in wanting to make their mark on art history by nurturing an image perhaps at odds with the facts, I wondered, How far will artists go in creating an identity and what have been some memorable examples….and why?

Arshile Gorky, for example, the mid-century painter who had a huge influence on Abstract Expressionism, was born Vostanik Manoug Adoian, but changed his name to words that meant in Armenian and Russian the “royal bitter one.” In their biography of Willem de Kooning, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swann write, “The name Arshile Gorky was apt: Gorky was both royal and bitter. Isamu Noguchi said that Gorky ‘created this character Gorky. And he had the physique and posture to carry it out and get away with it. Excepting that he was always, in a sense, playing a part, a role.’”

“Before receiving guests, Whistler had first to bathe, dress, and arrange his hair. Some people thought all the fuss unseemly, meant to ensure a grand entrance.”

Gorky was also somewhat of a dandy, affecting three-piece suits, elegant ties, and smart collars—dress starkly at odds with that of his scruffy younger colleagues. But if the outward image can be seen as another form of self-marketing, no artist was more adept at playing the fop than James McNeill Whistler, a short slight man who favored tousled curls, a tall cane, a flat-brimmed hat, and a signature monocle. Before receiving guests, reports his biographer Daniel Sutherland, “Whistler had first to bathe, dress, and arrange his hair. Some people thought all the fuss unseemly, meant to ensure a grand entrance. Whistler prepared himself as an actor applies makeup and dons a costume before appearing on stage….The purpose of all this being sales….” (Edgar Degas once called out to him, at a restaurant where both were dining, “Whistler, you have forgotten your muff!”)

Closer to our own times, Louise Nevelson became known for her gypsy head scarves and caterpillar-like false eyelashes, and in his ‘80s heyday, Julian Schnabel was famous for appearing in public in paint-spattered silk pajamas.

Tinkering with your physical appearance can also become the very basis for an artist’s art. It’s a tricky business, however, and can just as quickly lead to audience fatigue as to a Cindy Sherman-like pinnacle of fame. Consider the artist Colette, who made a name for herself in performances and living tableaux, affecting an ultra-feminine persona. She made a few waves in the 1970s through the ‘90s, but not much has been heard from her since. Ditto the French “sculptor” Orlan, who suffered through a series of plastic surgeries in the 1990s to assume the attributes of women in famous paintings: the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, the forehead of the Mona Lisa, the nose of Gérôme’s Psyche, and so on ad nauseum.

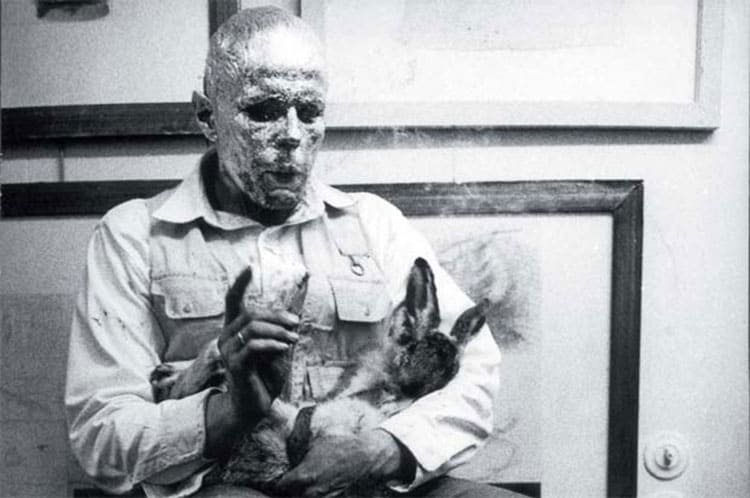

But perhaps the most intriguing form of self-mythologizing is the invention of an elaborate early history, especially when you’re on the cusp of fame or seem to have arrived. Many have questioned the details of Joseph Beuys’s account of his plane crash in the Crimea in 1944, when a group of nomadic Tartars allegedly found him and wrapped him in felt and fur to save his life. Eyewitnesses have claimed that Beuys was recovered by a German search commando, and there were no Tartars in the village at the time.

“Some have questioned Joseph Beuys’s account of his plane crash in the Crimea in 1944, when a group of nomadic Tartars allegedly found him and wrapped him in felt and fur to save his life.”

Beuys’s own account of the crash and rescue is wonderfully evocative: “I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries,” he later claimed. “Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That’s how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying ‘Voda’ (Water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.” His report also explains his fondness for two materials that appear frequently in his work, felt and fat.

How true was all this? Does it matter? As journalists like to quip, “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story.”

In the end, of course, what will really matter is the work and its influence. Few remember Nevelson’s grande dame appearances of the 1950s and ‘60s, and few critics would today would regard her sculptures as having an enduring importance in the canon of 20th century art. But Beuys has touched the lives and practices of scores of artists, and his legacy lives on—as it would whether he crashed in the desert and was saved by nomads or not.

But it’s a helluva fine tale.

Ann Landi

Photo credits: Jeff Koons

Entertaining….

Great read Anne, thank you

Wonderful article, Ann! I love the way you both brought them to light and undressed them with such precision.

Interesting stories, but as you say the art speaks louder and I have no time or interest in creating a myth for myself. xoxo

ditto! thanks Annie and Ann

Sometimes the need to create flows right into the reality of the artists persona to satiate that creative obsession. To manipulate that history may be another form of creating or art making. It may also follow an age-old business model, as Koons clearly personifies, to “dress for success” and in the case of an artists career to take that to extremes seems right for the job. Either way, what is art if not a little mystery, a little magic, or a scandalous reveal.

What a great story. I’ve always wondered about the value of having a “uniform.” Like you point out, people get bored and, like David Bowie, you have to kill the persona every few years . . .

“Few critics would today would regard her (NEVELSON) sculptures as having an enduring importance in the canon of 20th century art” Really?

Well, opinions will change, of course, but if you did a poll of critics today I don’t think they would put her up there with the greats: Louise Bourgeois, David Smith, Anthony Caro, Richard Serra, and so on. When was the last time you saw a Nevelson in a major museum or gallery show? But of course art history is as full of reversals as the stock market.