Even the most famous artists torch, shred, and otherwise annihilate works that don’t seem up to snuff

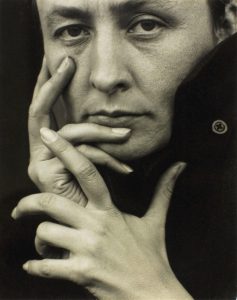

In 1967, Agnes Martin began seeking out her earlier works with the intention of destroying everything she could find. That was about ten years after she had decided to dedicate her energies to making paintings, drawings, and prints based on the grid—a radical formula at the time and one that brought her worldwide acclaim. In some cases, the older paintings were student efforts of negligible interest, except maybe to scholars.

Other canvases, though, came from her decade-long engagement with biomorphic abstraction, paintings considered accomplished enough to be exhibited at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York in the 1950s. Late in Martin’s life, one of her students lamented the loss of the work, saying that it was important to have it out there to show “young artists who are struggling that there’s hope.” But the artist remained adamant about her self-editing. If collectors would “sell them back to me,” Martin insisted, “I’d burn them.”

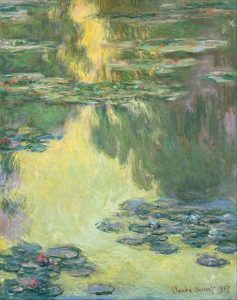

The number of works lost to art history, sacrificed by the artist’s own hand, is likely staggering. Claude Monet, to take just one example, destroyed a sizable trove of his famous water-lily paintings prior to a show in 1909. “He shredded at least 30 canvases, just slashed ’em up,” says Paul Hayes Tucker, a distinguished scholar of 19th- and 20th-century art at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Often, the decision to demolish is about an artist wanting to take control of his or her legacy before death wrests away that option. When Whitney Museum curator Barbara Haskell was working with Georgia O’Keeffe on a planned show in the early ’80s, she remembers the artist saying that “she wanted to go into storage to destroy some of the paintings that she didn’t think were at her level. When she got to the end of her life,” Haskell says, “she really wanted to purge, so that her reputation remained strong.”

An artist need not be middle-aged or at the end of a long and celebrated career to follow an urge to amend the record. Robert Rauschenberg was still in his 20s and had recently displayed some box sculptures and other objects in Florence in 1953, when a critic suggested he throw them in the Arno River. Rauschenberg cheerfully obliged. And when Gerhard Richter was in his 30s, he took a box cutter to several key paintings, including a 1962 portrait of Adolph Hitler, a 1964 picture of a kangaroo kicking a man, and a depiction of a warship hit by a torpedo, also from 1964. In all, Richter trashed about 60 early works, and a story in Der Spiegel placed a valuation of $655 million on the loss. “Cutting up the paintings was always an act of liberation,” the artist maintained.

Gerhard Richter took a box cutter to several paintings, now estimated to be worth about $655 million

In the fall of 1954, according to curator Mark Rosenthal, the 24-year-old Jasper Johns wiped out all of his art in his possession. “As soon as he got a handle on his esthetic, he destroyed everything. Right after that, he started working with encaustic,” Rosenthal recalled in an unpublished interview. Leo Steinberg, in his book Other Criteria, gives a more detailed account: “When Johns was discharged from the army in 1952 and settled down in New York, . . . he began to make small abstract collages from paper scraps. Being told they looked like those of Kurt Schwitters, he went to look at Schwitters’ collages and found that they did look like his own. He was trespassing, and he veered away—to be different.”

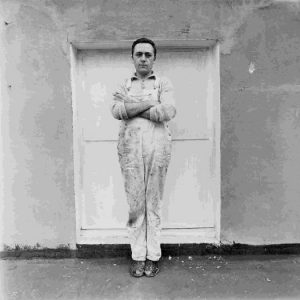

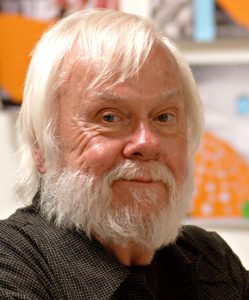

Most of these acts of demolition were carried out quietly, with little fanfare, the way a writer might consign early drafts of a novel or poem to the shredder. One exception is John Baldessari, who in 1970 burned all the paintings he had made between 1953 and 1966. Some of the ashes were deposited into book-shape caskets and exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York. He baked other ashes into cookies and put them in an urn. That installation, called Cremation Project, Corpus Wafers (With Text, Recipe and Documentation), was donated to the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., in 2005; it includes the cookies, a bronze plaque, the destroyed paintings’ dates of birth and death, the cookie recipe, a published newspaper announcement of the cremation, and photographs of the burning.

A couple years later, in 1972, American-born artist Susan Hiller, who lives in England, began placing the ashes of her own burned paintings inside test tubes with rubber stoppers, arguing that the results were “just as interesting to look at and experience as paintings.” In another series, she cut up her canvases and turned them into books. “There was a sense of finality and closure in cutting up a painting and making it into a block,” she says. Far more commonplace than these quasi-public actions are the artists who edit their creations as a part of their process. “When I don’t think a work is good enough to exhibit at the time I make it, I roll it up and put it away,” says Pat Steir. “I keep it for about ten years, and then I unroll it, look at it, and decide if I’ve made a mistake. Or I cut it up into little pieces and throw the pieces away.” Steir’s evisceration of past work is often practical and protective. “I once threw away a painting, and it ended up back on the market,” she says. (Her guess is that she’d asked an intern to discard the canvas, and it wound up on the curb.) “Agnes Martin told me, in 1971, if you don’t like a work, throw it away the way you would throw away a bad friendship.”

Ursula von Rydingsvard maintains a “graveyard” in a huge warehouse in upstate New York where she keeps the sculptures she “just can’t deal with.” She estimates that she gets rid of about 20 percent of the pieces she’s working on. “Periodically, I go there and I see something that looks like it might have hope,” von Rydingsvard notes, “but it’s never the whole piece. It’s usually just portions that can serve as a springboard for other works.” Recently, Petah Coyne decided to pull all the work she’d never quite finished out of storage and look at it for a couple months. She and her assistants “destroyed probably 70 percent of it,” she says. “I do this every five to seven years, and then I just have to finish the others. As you get older, you look harder,” she adds. “You don’t think everything you do is brilliant.” When scrutinizing a piece, Coyne asks herself, “‘Would I be thrilled to see this in MoMA?’ If not, out it goes.”

Ursula von Rydingsvard maintains a “graveyard” of works she “can’t deal with” (Luba, 2010, at Storm King Art Center, photo by Jerry L. Thompson)

Sculptors and painters aren’t the only ones to do away with work that doesn’t measure up to their standards. Anne Wilkes Tucker, curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells the story of Robert Frank, who stopped at the home of photographer Wayne Miller midway through shooting the series that would become “The Americans.” Frank “developed the negatives that he had made thus far,” she says, “and on that first look, he cut and threw away some and kept some.”

Later, Frank became a filmmaker and lashed out at his photographic past through his new medium. “There’s a famous image in one of Robert Frank’s movies where a friend of his is drilling through a stack of his prints. Frank was trying to put ‘The Americans’ behind him,” Tucker says. “It’s hard when the first series you make continues to be regarded as your most important work, and that may not be what you want.” Similarly, the curator points out, when Edward Steichen abandoned painting for good and took up the camera, he “burned his early paintings in France.”

Given that much art nowadays is by its very nature ephemeral—sharks that rot, installations that will be disassembled, performances that may or may not be repeated—maybe the sensible solution for some artists is to plan for the ultimate dismantling of their work. Karlis Rekevics, a sculptor who describes himself as being in a “dialogue with the built environment,” says that most of the pieces shown on his website don’t even exist anymore. Though his large works in cast plaster have been exhibited in major New York venues like MoMA PS1 and the SculptureCenter, Rekevics “physically smashed them with a sledgehammer, cut them apart, and picked them up with cranes and put them in dumpsters,” after the shows ended. Perhaps because of his background in the temporary art of theater set design, he finds the process of creation “more interesting than the outcome.”

What has been lost to art history through the destruction of those “Water Lilies” and of any number of early works by any number of major figures is, of course, incalculable. Still, curators and scholars will be the first defend an artist’s right to self-edit. “There are some artists whose reputations have been damaged by the fact that they have so much art in the world, where the market and the amount of work, of both high and low quality, has saturated our experience,” says Haskell.

On the other hand, “artists may not always be the best judge of what should be their permanent legacy,” Paul Hayes Tucker says. “It’s history lost, and we have to live it.”

Ann Landi

I love this topic. What a great survey.

What a great topic – loved this piece

Monet’s children used to use some of his paintings to make canvas boats that they used in the pond. All was not lost, just repurposed.

Perhaps you should do a piece about when artists destroy the work of other artists. Rauchenberg/deKooning, Schnable/Salle, Manet/Morisot, Schifrazi/Picasso