Slowing down, filtering out the noise, and allowing the mind to empty out can offer a tremendous boon to the creative process.

Gina Telcocci, Our Body is a Flower (2016), plywood, willow, mixed media, sound, 46 by 22 by 22 inches

Meditation has for years enjoyed a reputation for its restorative powers and its abilities to sharpen the senses (as well as provide deep inner peace). The artists polled here have all come to practice one form of meditation or another—from following strict Buddhist conventions to practicing Asian brush painting to engaging in “walking” meditation.

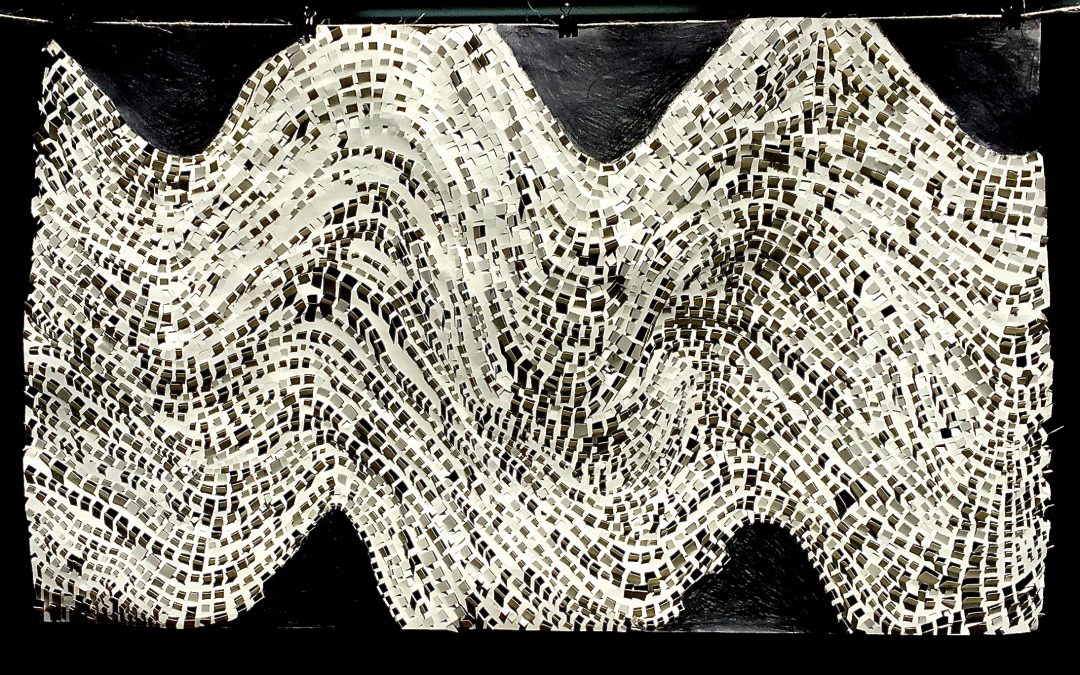

Some will tell you that the process of making a work is in itself a form of meditation (and there has been some medical evidence to bolster that claim). Ty Zemelsky, in describing her “cut drawings” (above), says, “I work deliberately, warming up for as short a time as I can before I slip into a meditative state where I think that I am most alive, responsive, and unself-conscious, as opposed to the usual experience of watching myself live. Of course, when it is happening I do not know it. But I certainly know it when it is not happening. The meditative process of making repetitive movements, repetitive lines and shapes, becomes the breath and music of the drawing.”

Or, as Gina Telcocci succinctly puts it, “I don’t need no stinking meditation—making art is meditation.”

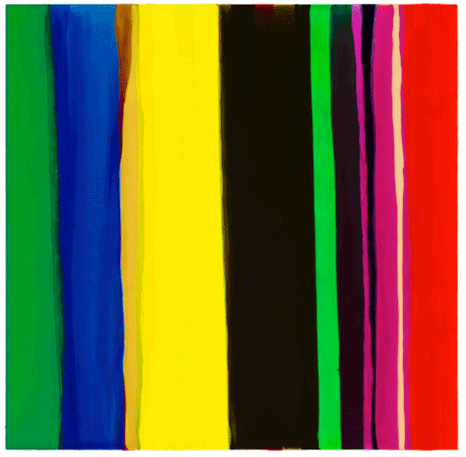

Hester Simpson

The first thing I do when I get to my studio in the morning is pull my spattered old ergonomic chair into a specific spot and meditate for 20 minutes. If for some reason I can’t spare 20, I’ll do 5. It’s more than a habit now; it’s a necessity.

Meditating helps me move more directly into my painting than if I just walk in and start working. The simplest way to describe the meditation I practice is that I STOP. I sit in the same spot every day with my back to the wall and feet on the floor, hands loose in my lap while any and all thoughts float through my brain. My eyes are just about closed. The only difficult part of this meditation is in not allowing myself to get stuck on any one thought. But as I practice, I get a little better, very very slowly.

This STOPPING is sustenance for the functioning of my brain. Even if I haven’t sufficiently unscrambled my brain, it’s at least not as concerned about that condition. I move on.

My work is obsessive and it’s easy to get bogged down in it. After I meditate I look at what I’ve been painting. Ideas and decisions come more easily. I don’t endlessly judge my own judgments. I am less tentative in the handling of my materials and in making moves.

Saya Benham

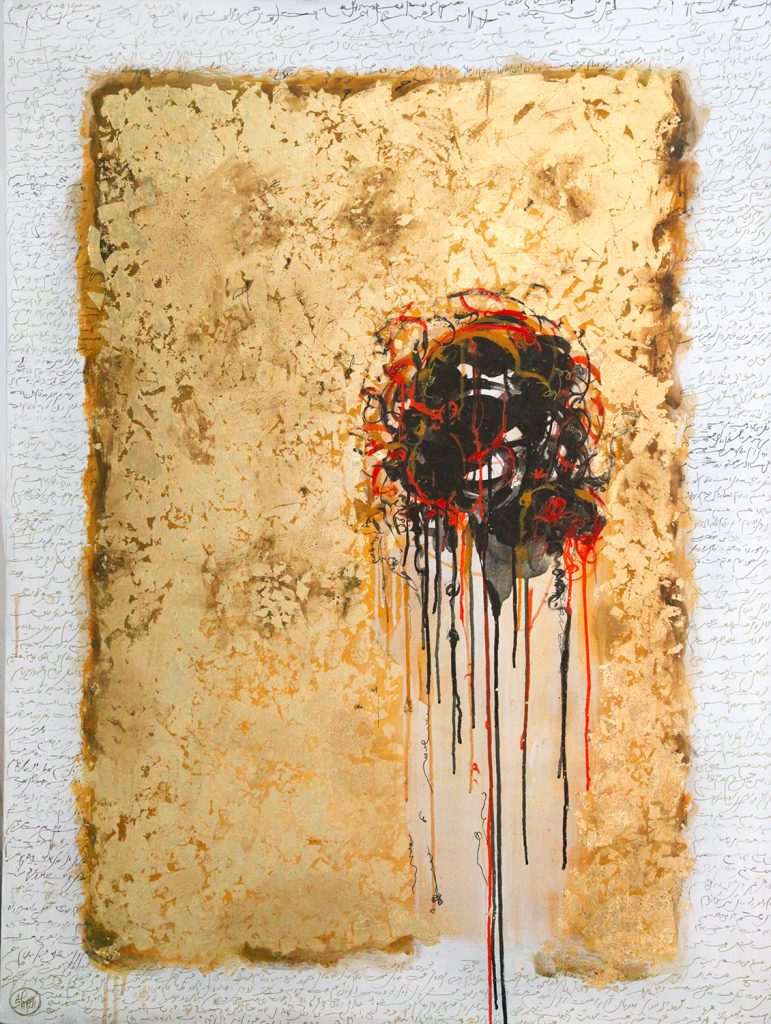

Saya Benham, Between Being and Oblivion (2015), acrylic, gold leaf, ink, pen on canvas, 30 by 40 by 2 inches

Adding small gold flakes next to each other while I am painting is a meditative process. Nonetheless, I do 15 minutes of silent meditation before or between my painting sessions; these clear my mind and often a new idea pops up. I don’t know how and when, but I’m pretty sure meditation has a huge effect on the process.

At the beginning of a meditation session, I normally focus on my breathing. I don’t force my mind not to think. I let all thoughts enter my brain and simply watch them. Let’s say a task or a conversation I was very involved in that morning keeps coming to my mind. I let it enter, but like a third person, an observer, I make myself aware that it is just a thought and it will come and go. Let it be there as much as it wants. And then I return to breathing,

The purpose of meditation, at least the way I understand it, is not to stop thinking but to watch your thoughts.

Robert Parker

I have meditated for many decades and have found that it is very much a part of my art making. Following the Vipassana method (“insight meditation”), I find that the mind clears and sometimes a direction for a new work emerges. Other times, it does not happen. I have never tried to free my mind when in a meditative state of any images or insights that might surface for my work. Some would say this is an interruption and that the mind is not free of everyday concerns, but I don’t see it that way. I see it as a great gift. This is to say that meditation is a foundation for my art, not an end in itself. While one operates on the conscious level and the other on a more subconscious level, both are intertwined. And the influences flow in both directions.

The great joy of being immersed in the act of art making to the exclusion of other outside influences is to recognize that the mind is quiet, meditative in nature, and working in a basically an autonomic manner.

Meditation is not art and art is not meditation, but often the process of preparing for making art can be preceded by the meditation process. The mystery that ensues is not explainable, nor should it be. It is enough to recognize that both states are at work, however non-rational it may seem at times.

Jane Barthes

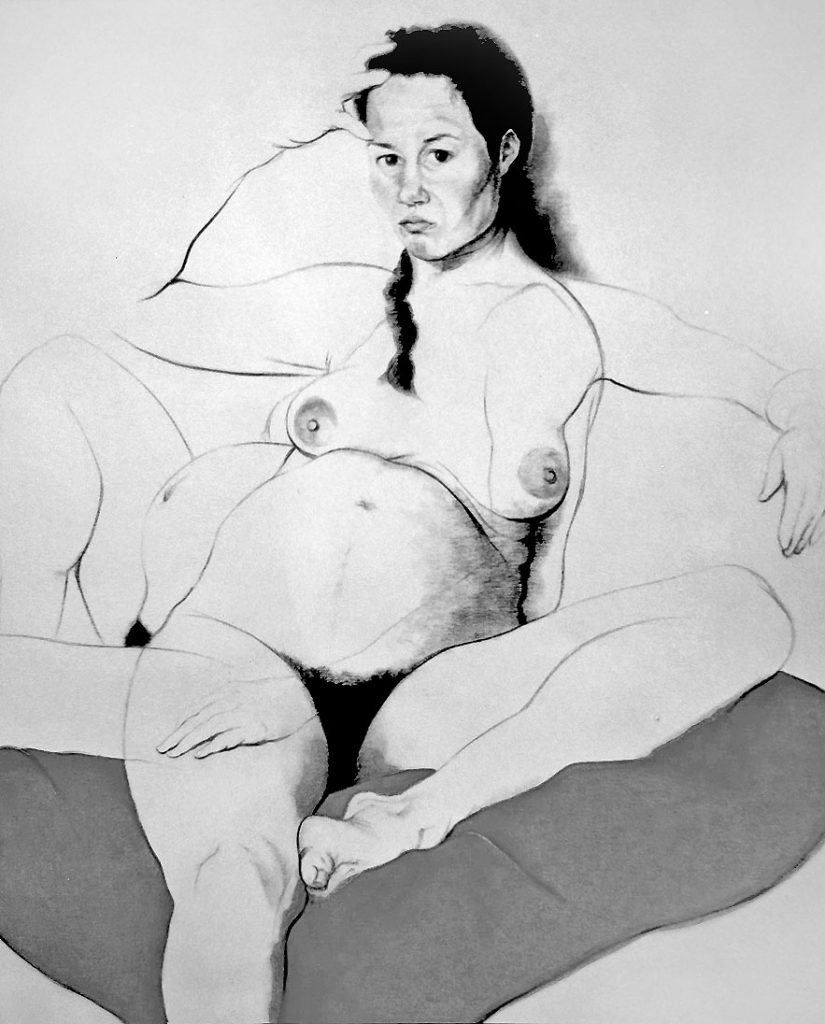

Years ago, I was working on a very large drawing of a nude, pregnant woman (who gave birth a week later). I would stand back and just look, I mean really look, without making a mark until I somehow felt ready to commit. I remember gliding the charcoal stick through a line from her armpit to the tip of her little finger without lifting or hesitating for a second. The line was so alive—so damn perfect—it actually freaked me out a little. And certainly gave me cause to think. So began my quest to understand and develop what I came to realize was the notion and practice of being utterly present to the moment in time. I realized that in that instance of looking, there was no separation between me, the object (my model), and the paper. We were simply one. Establishing that presence has quietly gone on informing my practice. It was incidentally also the moment I broke away into abstraction. I have spent years meditating on a black cushion (the zafu), and I’ve been to numerous retreats in my time, but nothing brings me to be “present to the moment” like my art.

Annie Coe

I practice a kind of walking or hiking meditation. You start out thinking about what you’re doing with your feet, how the ground feels, the air around you. You don’t want to focus in on one thing, you want to have a sweeping feel of other things—what’s going on inside and outside of you. It’s hard to pay attention to both at the same time, but for a brief moment that can happen.

I like to hike, and I take my dog with me. I find that somehow the experience of nature gleaned from hiking filters into my work. I am picking up things from the landscape, colors, textures, and it feeds into my art

My paintings used to be very bright and chaotic, but my work has changed tremendously since I started meditating and hiking after I moved to Taos, NM, 20 years ago. When I look at my paintings, I see that now the quiet has entered into the process and settled into the work. It took a while for that to happen, but now my work bears little resemblance to what I was pursuing earlier.

Arlene Rush

I began practicing Buddhism in 1991; since 2005, I have been with the modern Kadampa Buddhist tradition.

A couple of aspects have affected my art. When I started meditating in the early ’90s I began having visions, I was making these flame-like vessels out of clay that came straight out of the process. Then later I started using the form of genderless heads to talk about philosophical ideas: the stripping away of the self that we normally see does not exist, and creates in us a feeling of being separate and isolated. Uniting the gender to an androgynous head created a feeling of unity and connectedness.

My work consists of multiples, I am doing the same things over and over, and that repetitive act can be tiresome or it can become a meditation practice: it helped me find a way to transcend boredom through focus and concentration. Nothing is the same, each moment is different.

Millicent Young

For many years I have walked the land I live on every day. I follow a trail–originally a deer trail–that loops through meadows, woods, along the river and back. It is important that it is the same trail. It is a paradoxical experience of utter sameness and complete change depending on the season, the light, the air, the snow, the leaves, the rain, the presence or absence of animals, birds, insects, vegetation, my frame of mind, the thoughts that come with me, the ones I leave behind; the epiphanies I find, the weight I carry. Walking can create the same open field of attention that my silent meditation practice can create but not the trance-like state. That field is where imagination sparks and ignites something – which often finds it way into my studio practice. This walking is a solitary practice. What I have described does not happen when with company.

Susan Christie

Meditation, for me, has to do with the practice of quieting the mind. Decades ago, I discovered a book by Diana Kan, The How and Why of Chinese Painting, and had a visceral response to the images of poured black ink and bright mineral pigments. Some research led me to Minnihon, the Japanese Cultural Arts Center in Minneapolis, directed by Reiko Ito Shellum, daughter of the Japanese Ambassador to Mexico. I studied with her for ten years.

One afternoon, she suggested I spend the time, three hours, with one brush stroke, painting a bamboo leaf. I did as she directed, and paid attention (mindfulness).

Using the traditional materials of Asian brush, ink and paper, everything slows down. The brushes are handmade; the ink is made from charcoal bound together with rice glue; the papers range from very soft to less absorbent. Dip the brush in the ink and water and watch it slowly creep up the brush hairs. With your entire body and attention, you move your energy and brush the ink on to the paper, watching the two meet. In Western art there is nothing like this connection between the person, the materials, and the moment.

Now meditation has become a part of my life as a whole—if I’m cooking, gardening, or doing some other project. It’s a mindfulness of the present moment. The more you practice, the easier it is to get there.

Paul O’Connor

What you try to do is non-doing, abiding in the present. Every morning my wife, Tizia, and I meditate from 7.30 to 8.00 and then do 40 minutes of yoga. Every Wednesday we have an hour-long group meditation that includes 20 minutes of reading and texts, a sound session for 20 minutes, and then absolute silent meditation.

There are thousands of meditation techniques, I follow one called Dzogchen. I embrace the thoughts, not pushing them away because that’s a form of resistance. To give an example, if you have a thought like, “I want to kill my neighbor,” you see that thought and then you start seeing the space around the thought, asking yourself, “Where did that thought come from?” It came from a black hole, and then it’s going to disappear. When you start thinking in terms of spaciousness you see that thoughts appear, they manifest themselves, and then they dissolve. There are three elements we abide in: spaciousness, silence, and stillness. This is the natural state of things.

My point of departure into my sculpture is meditation because it sharpens the mind.

Irene Nelson

Aging and art making are “not for sissies.” I find meditation to be helpful in both areas.

I have gone to numerous Dharma talks and residential silent retreats, and follow the Vipassana tradition, practicing from 30 to 45 minutes a day. Thirty years ago I gravitated to studying Buddhism and have come back to it off and on, making a more concentrated effort over the last five years, I find that meditating prepares me to be open to discovery, to deal with fear, and to be kind to myself because I can be very self-critical.

As I become absorbed in the creative process—working to discover imagery that has always already been there, or waiting for it to emerge—the creative process itself becomes the answer to the question.

It’s helpful to have a conversation with yourself, to give yourself the time and space not to make immediate judgments. And then I can bring myself to the painting Iprocess, and I can see patterns emerge. Not always right away—but I can say, “I know this pattern and I see where it goes.”

Top: Ty Zemelsky, Searching for Orion (2016), paper, ink, graphite, baling twine, plastic clips, 24 by 41 by 3/4 inches

Thank you Ann for including my story, great article. xoxo

Very interesting to see how other artists practice meditation.

Interesting to learn about the many forms meditation can take. Thanks Ann!

Terrific article, thank you. Meditation transformed my work. Love how Millicent Young described walking meditation, which I prefer to sitting.

Here’s to you, Ann, for once again creating community where it is sorely needed. I love reading about the different ways these artists practice meditation and am honored to be included. Rock on! xoxo

Interesting. My experience is with Zen and my first Zen teacher was an artist in Truchas, ALvaro Cardona-Hine, who just died, about a month ago. I practiced sitting meditation with him three early mornings a week, and later went to multiple retreats with other teachers – finally I realized what a commitment it is and how I had to decide between Zen and the studio. My teacher told me that the studio practice would be equivalent, and it’s what I chose. But actually, the Zen practice is not only different and harder but more powerful. Nevertheless, I have opted for the studio. I hope that Zen informs my work, but I know I chose the easier route – also the route that could not be compromised by sending time and energy elsewhere.

Somehow I missed this article until just now. It’s wonderful. Thank you so much Ann and all the artists who contributed.

I really enjoyed this article. Thanks for thinking to write it for all of us. It’s very helpful.

Another nice article Vasari 21! Thank you Ann! Meditation has been a part of my studio practice for more than three years now, I find it to be very helpful not only in the studio but outside of the studio as well!!!

Late to the party but this was a great article! Especially respond to Irene Nelson when she says “Aging and art making are “not for sissies.” I find meditation to be helpful in both areas.” I totally agree!

Happy to find this article. Meditation forms the ground for my work too. Couldn’t be an artist without its allowing me to be connected. It’s the wellspring.