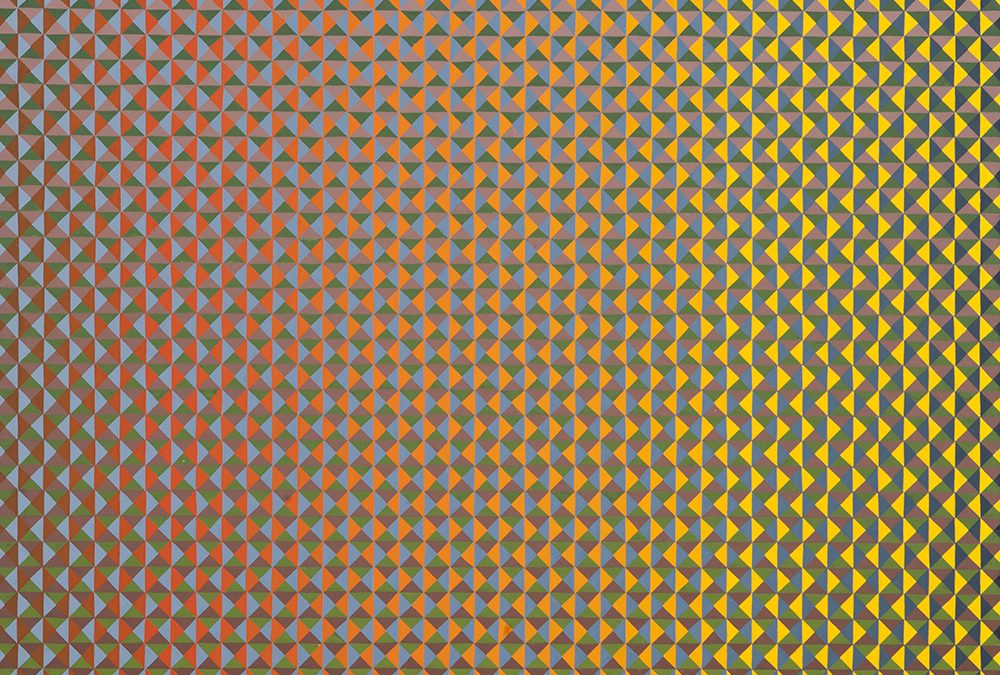

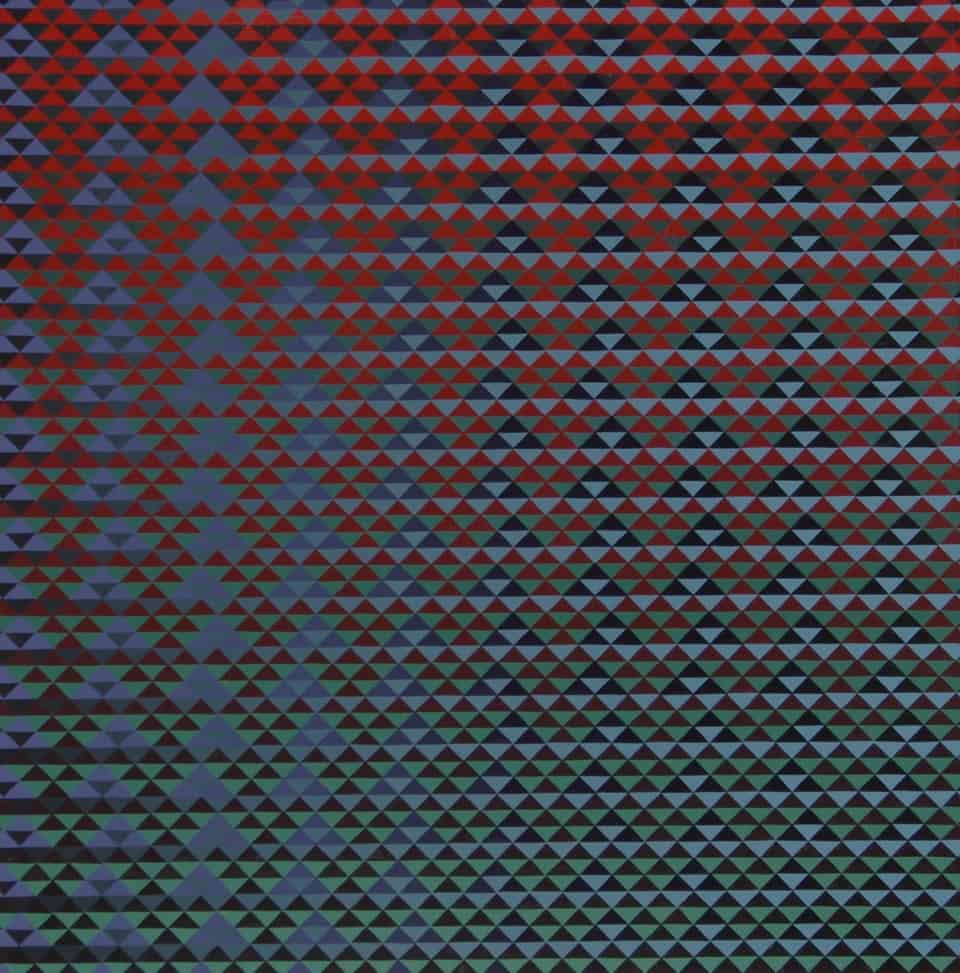

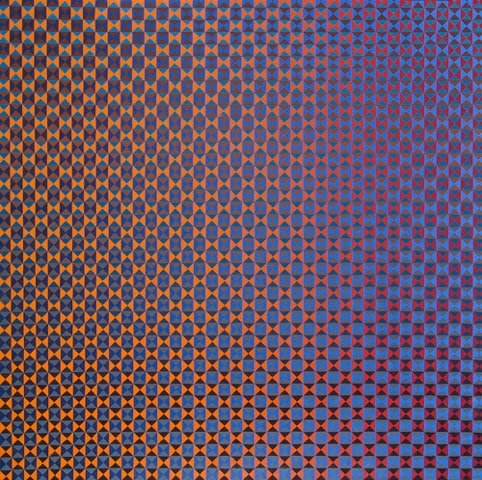

At first blush, Annell Livingston’s tightly gridded abstractions might appear to be successors to the Op Art frenzy of the 1960s, but on closer scrutiny her gently rippling canvases are not so much interested in playing visual tricks as in conveying the passage of light and a feeling of transience. They may recall, for instance, the journey of late-afternoon sun across a wall or floor; their poetry finds its antecedents in Agnes Martin, not in Bridget Riley.

That Livingston is an artist at all is something of a miracle. As a girl growing up in a small town outside Houston in the 1950s, she spent a lot of time painting and drawing and claims that you “could do whatever you wanted to do as long as you didn’t embarrass anybody too badly.” But in high school, she was told that the only career options for women were the tried-and-true trio of “nurse, secretary, or teacher.” At the University of Houston, she studied home economics (“I became a terrific tailor,” she notes) but changed her major to art. “I didn’t want to be a teacher. I just wanted to paint.”

Married at 21, she describes herself as one of the “oldest taken-care-of women in my neighborhood,” But she painted every day and also took classes with Lowell Collins, the former director of the Glassell School at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. She also returned to the University of Houston to study ceramics, printmaking, and experimental painting.

Eventually she had a studio downtown, and although she had been steadily working, she had a moment of truth in 1991 “I closed the studio door and alone with myself, I asked, ‘Who am I, and what do I really want to paint?’” as she recalls in her online biography. “The answer was that my life was an urban experience….I began creating grids based on the square, which seemed to be the perfect symbol for city. As I drove to the studio each day, I would observe the light as it was reflected off manmade surfaces and made notes in my journal. The notes or words I chose became the inspiration for the color of the paintings.”

In 1993 Livingston’s husband drowned in a freak accident. The blow was devastating. “My husband had been my boyfriend since I was fourteen years old,” she says. Not long thereafter, a landmark Agnes Martin retrospective, which originated at the Whitney in New York, arrived at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston. “Her work was very comforting to me,” says the artist, and the encounter with the doyenne of Minimalist painting seems to have reinforced her own inclination toward structuring with the grid.

A year later, Livingston moved to Taos, NM, and the momentous change from urban density to high-desert isolation had an impact on her work. In a series called “Poems of the Desert,” she drew shapes and selected colors from the landscape around her. “These works are not about what the desert looks like but what it feels like as an actual place or metaphor,” she says. “My work is not so much about the external world, but about finding that place where the internal worlds meet—heart, mind, and deed.” She called a later series “Fragments,” because it seemed that her “thoughts and memories were like fragments, or bits and pieces. Nothing seemed really whole, but the pieces came together to be the experience of my life.”

About a decade ago, a dealer in Santa Fe asked Livingston if she would be willing to try her hand at still life. “It took me a while to get to the point where I could paint these,” she recalls, “but when I did, I wanted to make something that everyone else wasn’t doing.” She looked for motifs and subjects native to northern New Mexico, collecting Mexican pottery and using local flowers and vegetables. The results were pleasing and marketable, but not ultimately where the artist wanted to go. Gradually she began abstracting from the still-life images, pulling apart the compositions, re-introducing the grid, and arriving at a kind of abstraction where the original image has almost completely disappeared and small geometric units remain supreme, producing an illusion of subtle gradations and nuanced change across the surface. “it seems I work in a series until I have exhausted it, or myself, or put it away and then after a time I return to it, and it’s new for me again,” she says.

Of her tendency toward reducing images to their most basic components, she says, “The simpler something is, the more the doors open to creativity. You think, ‘I’m sure I’ll get tired of this pretty soon,’ and then you see new possibilities.” Like many an artist before her—one thinks of Mondrian or Josef Albers—Livingston has discovered that, almost paradoxically, limiting the parameters can expand your horizons.

Annell Livingston has had many solo shows throughout the Southwest and in Palm Desert, CA, and Gunma, Japan. She has recently participated in juried group shows in New York, California, Texas, and Maryland.

Top image: Fragments Geometry and Change #212 (2006), gouache on watercolor paper, 30 by 30 inches

Ann

By God, I think you Got it!!! Thanks so much for the organization of my “house of cards.” I love it, couldn’t have done better myself!!!! What an article, I am so proud!!! You really get me! Your writing is outstanding!

Fantastic and Congratulations to my friend, the Artist. Love the exploration of your work and how it changed and moved over time, like your current paintings. Well deserved acknowledgement, Annell,

Elizabeth

Annell Livingston is truly one of the most gifted and giving artists living.

I have had the good fortune to have watched her work over decades and she continues to inspire me.

One artist writing about another artist, well done. It’s wonderful. Annell you are wonderful, and it shows in the depth and beauty of your passion.