What does it mean to be a “regional artist” today?

By Millicent Young

Bradley Sumrall, curator at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, posed this question in his juror’s talk for “Homeward Bound,” the Taubman Museum’s inaugural triennial for Virginia artists. I resisted considering myself regional in spite of being residential in the small town of Ruckersville. My relationship to my locale was not an easy one politically and culturally, and personally it was a site of violence and loss. It was true that some of my materials were indigenous, that I had made work of what had happened, that this place shaped the rhythms of my work, and that I would benefit professionally from the recognition I had earned. None of this made me right with being identified as a Southern artist in 2017.

But Sumrall’s question, which asked more than it answered, provoked me. I began re-reading the artist statements of friends and fellows in a new light. Indeed, place figures prominently yet uniquely in our narratives—as natural, cultural, and psychological landscapes; as the source of materials; as physical parameters of our studios that shape what we make; and as the site of memory—as though memory and place spool as one, two threads inextricably twined.

And so I decided to begin a freewheeling conversation with four artist friends about place: What is place and what influence does it exert on our work as artists? Are place and memory separable? When we move through place, do we move through memory, not only our own but also the stories contained by the place? Is place a broth of materials and images that we ingest and then express?

By pulling our conversations together into an essay form, I created for myself the nearly impossible task of editing our phone and email conversations and weaving them into a coherent whole while shouldering the mandate to do justice to the amazing work and large lives of my artist friends. What follows is some of the places our conversation went though what mostly interests me now is where it will go.

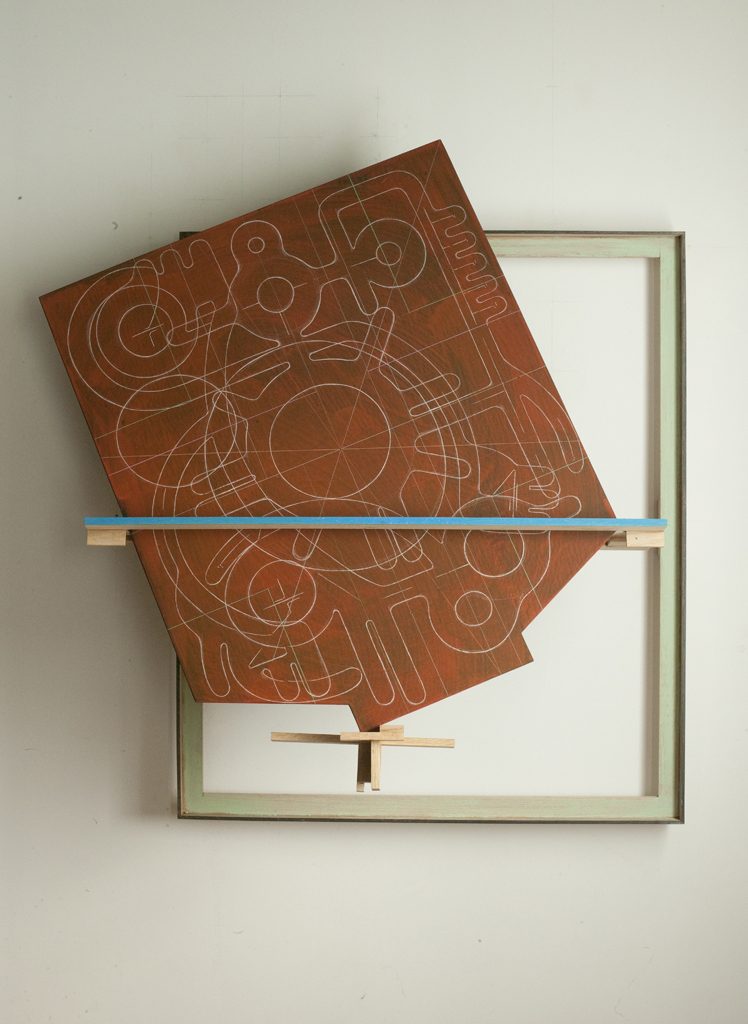

Andrew Lyght, KL031 Drawing Structures (2016), oak frame, oil stick, acrylic, and pencil on plywood, 44 by 49 by 17.5 inches

“I am a nomad in my visual memory, constantly moving backward and forward between my childhood in Guyana and my life’s journey since moving from there to several cities on three different continents,” says Andrew Lyght. “One of my earliest and most important childhood memories was watching my uncles and neighbors build stick-frame houses. I thought that these pared-down, open structures resembled line drawings in space. It was these lines against the sky that led me to imagine and create structures that could fly and float in space. I made and sold kites for pocket money. I also flew kites that were much larger than myself.”

Andrew was born in 1949 in the port city of Georgetown, Guyana, a country “monetarily poor but culturally rich” on the north shoulder of South America’s Atlantic coast. Steel hulls of ships, water lines of rust, sails of fabric, and the methods of their construction inform his visual language of space, line, color, and form. His work is an extensive oeuvre spanning nearly five decades. It moves freely across dimensions and scale: billowed planes of ink-dyed canvas on bamboo structures; exact forms that float on ropes and pulleys; precisely deconstructed then reconstructed frames in wood and steel; overlaying architectural lines that evoke geoglyphs on color-saturated paper; geometric steel shapes rusting patterns onto paper or canvas with taut colored lines strung through the picture plane.

Andrew Lyght, G741 Drawing Structures (2017), oil frame, oil stick, acrylic, and pencil on plywood, 45 by 40 by 14.5 inches

Andrew moved to Montreal to continue his art studies and then to Brooklyn in 1977, where his studios were in industrial spaces at PS 1 in Queens, and then in Williamsburg and finally Greenpoint, both in Brooklyn. Throughout his life, he has also done construction for wages and there is an exchange between his art making and his paid work in terms of processes, materials, and tools. After losing his studio in Brooklyn in 2004, Andrew learned CAD programs to continue his artwork in digitally fabricated spaces while he embarked on a nomadic life abroad. Looking at photographs of his work, of his sprawling industrial space in Brooklyn, and then visiting his current live/work space in Kingston NY, I saw the flow. From the carefully drawn lines that lace the exterior entrance to the shape of the indigo sink; from the flood-water mark preserved on the brick to the cables of the loft railing; the bed frame he was making, modular so that it can be carried up the nearly vertical stairs and assembled in his sleeping loft—all this existing among his artworks and tools in one place woven tightly with strands of visual memory.

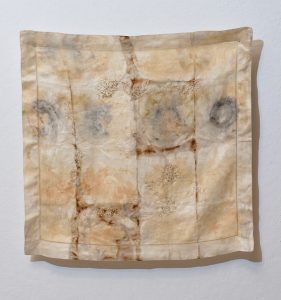

Brece Honeycutt, Bewildered (2016), eco-dyed textile, flax, and silk/cotton thread, 21-1/4 by 22 inches

Brece Honeycutt lives in a colonial farmhouse in the rural Berkshire region of Massachusetts. A former resident of New York City and Washington, DC, she makes “nature-based and history-based drawings and sculptures and installations.” She also describes herself as a “citizen naturalist.” Her daily walks through urban and rural places are an important part of her practice. More than scavenging expeditions, they seem to invite ‘getting lost.’ Brece says, “On my walks, I often feel bewildered—amazingly lost in the wilderness, seeking signs and writing down observations.”

Brece Honeycutt, Winterfield #5 (2017), silk cotton/thread on linen, 15 by 15.5 inches (photo: Douglas Baz)

“Place for me is where one lives, but place is also defined for me by the books I read that relate to a particular place. Place is also one’s imagination of one’s physical environment that imbues that place with further meaning” writes Brece. She continues, “Often my work is made from materials gathered from the land surrounding my studio. The imagery may be gleaned from the land itself.” The materials that her place offers her include rusted nails pulled from the farmhouse clapboards; goldenrod for making dye; urban discards; nut hulls; scavenged textiles; and the contents of old handwritten diaries she reads in the local library.

Brece’s relationship with her place in its natural, cultural, and historical aspects is breathtakingly intimate and this intimacy is telegraphed in her work. The found materials are reworked, becoming an element of the larger fabrication. The intimacy is expressed not only by the still-intact memory of the original found object but also by the careful witnessing of the artist. “Studio mornings consist of reading, research and gathering natural and historical elements. The act of stitching onto dyed cloth brings me back to the glimpsed lichen on the tree, the lines on the birch bark, the frozen ice on the pond, and the sounds of the birds in the woods.” Without that witness, the crumpled handkerchief, the single pigeon feather, and the place and story they stand in for would be unremembered, unimagined.

Norton WR, Traveler (2016), clean and colored hand-carved plexiglass, wood, patinated copper leaft, 55 by 101 by 18 inches.

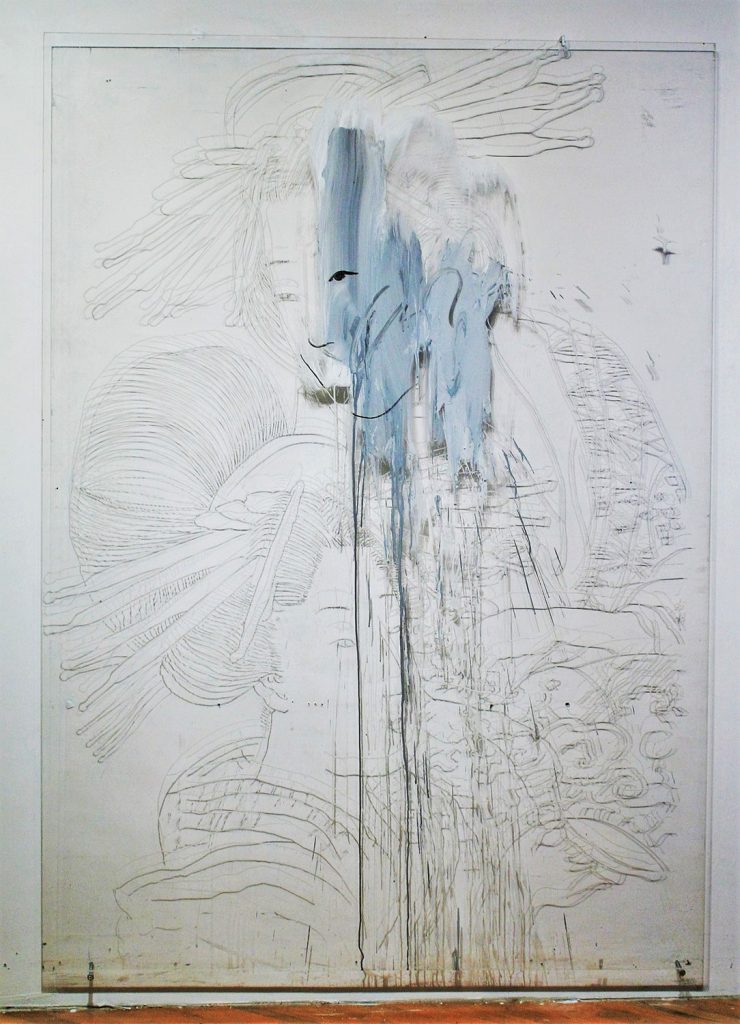

When he was a child living in Japan, Brooklyn-based artist and curator Norton WR read the classic Japanese fairytale “The Boy Who Drew Cats” and knew he would become an artist. It is the story of a boy who draws cats obsessively. Once upon a time, the boy drew them on the walls of an abandoned temple where he had found shelter. During the night, he heard terrifying sounds and upon waking, found a huge dead rat. The cats had come alive to kill the rat-demon that haunted the temple. By morning, they had reverted to their still form on the walls, claws bloodied. The temple, which had become derelict and haunted by demons, was re-sanctified, and the boy became celebrated as a great artist. Art is the vehicle for redemption. For Norton, working in the studio is a transformative act of “reaching beyond who and what we are and putting us in touch with a greater knowledge—that connection between hand, eye, and heart resonates within my soul.”

The illustrations that accompanied the story were equally influential for Norton. “Very naturalistic, very delicate, they inspired my hand.” Yet a larger template of Japanese aesthetic runs through his work: exacting geometries; the traverse of nature between interior and exterior; the play of light and shadow; the perfect voids and the sense of contained force in a becalmed place. The etched lines on the surface of transparent Plexiglas that Norton makes create a shadow play on the wall behind and a tracery of white lines on the clear foreground.

Borrowing from his New York City landscape of tiled subway tunnels and stairs—as well as from other imagined or remembered landscapes—Norton carves the setting in which psychological journeys, creation myths, and his narrative of personal loss unfurl. The silhouetted figures that inhabit these sometimes life-sized works are vacant, existing as a memory or a trace of what had been. Presence and absence collide within the grid that holds a human story. The viewer’s own shadow projects onto the work creating a moving layer that both temporarily inhabits and obscures the narrative. Where panels of the etched surfaces overlap, the imagery becomes dimensional, as in dreaming, where the ephemeral and the indelible meet.

Julie Hedrick is an abstract painter whose love affair with landscape began in Nova Scotia where she was an art student. Born in Toronto in 1958 into a family of artists, she has made Kingston, NY, her home since 1990. The play of light through air, refracted and reflected by mist and cloud, the tall sky and the flat Hudson River inform her visual imagery. But color is her primary language. Though her work has been described as “modernist readings of the Hudson River School paintings” (Jonathan Goodman, Art in America, 2000), the subject matter of her paintings is myths, energy fields, and dreams.

In her 2016 solo exhibition “Ariadne’s Golden Thread” at Nohra Haime Gallery, Julie used the Greek myth of Adriane and Theseus to make paintings as invitations to an internal place of illumination and beauty in our contemporary time of monsters and dark labyrinths. Like 50 words for snow, Julie lists some of the colors in this series: dark violet blue black; violet pale grey; violet pink; yellow rose; pink rose; gray gold; bronze gold. The work in her “Alchemy” series uses the quest for the philosopher’s stone—the magical substance that would transform dark matter into gold—as its template. The source of her imagery was the single experience of seeing the early morning mist over the black water of the Hudson dissolving into the golden light of the new morning. In the “Alchemy” series, her palate is a seemingly infinite range of whites, grays, blacks, and golds.

In addition to being a painter, Julie is trained in alternative-healing modalities of touch and sound; writes poetry; and collaborates with her husband, composer/musician Peter Wetzler, on performance-based work. Together they are innkeepers of Church des Artistes, their B & B cum studio cum residence cum community gathering place in an historical church in Kingston, NY. There they have raised their children, make their work, and help foster a community of creatives.

It was there at their kitchen table, when I was visiting and searching for a new place that I recognized I had come home. “When I think about place I imagine so many different kinds of places,” says Julie, “the places we know from experience, here and now, the places we know but haven’t been but exist in our imagination, the places we go when we dream. The ‘place’ of dream does exist, without borders, without definitions like countries or religion, a place of collective consciousness.”

It is from that region, I think, that we work as artists, though we are voracious observers of all that fills the field of our carnal senses, evanescent minds, and kaleidoscopic relationships. Our observations percolate into a deep collective cistern and issue forth as forms and marks filtered by our particular present, as intimate as they are universal.

Millicent Young is an artist in transition from Virginia to Kingston, New York. She has contributed several essays for the site.

Top: Brece Honeycutt, installation view of “Summer Rubbings,” on the rotunda wall of the Hyde Collection in the exhibition “MHR-80” (2016), dimensions variable. Photo: McLaughlin Photography.

Well written piece about our sense of place

Thank you Ann Landi and Vasari 21