One by one the old, bad monuments come tumbling down. In the wake of the brutal murder of George Floyd, protesters removed statues deemed racist and offensive, focusing first on heroes of the Confederacy like Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. But the protests extended across the pond to statues that celebrated slave traders like Edward Colston and Robert Milligan in England. King Leopold II in Antwerp, Belgium, notorious for atrocities against the people of the Congo, came down on June 9, and on June 12 in Hamilton, New Zealand, the Maori people toppled John Fane Charles Hamilton, who led an attack that killed scores of the indigenous people in 1880.

Slated for removal: Teddy Roosevelt and friends in front of the Museum of Natural History in New York

Christopher Columbus, that great granddaddy of crimes against humanity in the U.S, was yanked from his pedestals in Richmond, St. Paul, Denver, and San Francisco. Teddy Roosevelt on horseback, flanked by a Native American and an African, in front of New York’s Museum of Natural History, will soon be removed.

And in my own neck of the woods—or more specifically, corners of the desert—statues of Juan de Oñate in Alcalde and Albuquerque, NM, came under attack. Oñate, who ordered the massacre of more than 800 members of the Ácoma Pueblo, lost his right foot to a protestor in Alcalde 20 years ago, in retaliation for one of his most vicious acts as governor. In 1599, after enslaving 500 of the remaining Ácoma, he ordered that men over the age of 15 have one foot amputated.

The desecration or outright removal of statues deemed offensive to contemporary politics and sensibilities is nothing new. As historian Mary Beard points out in a blog post, “there are any number of references in ancient writers to the statues of the short-lived would-be emperors in the civil wars of 68–69 CE being thrown away, just as soon as another very temporary new emperor arrived on the scene.” Sometimes, she notes, it was simply more efficient “to give a makeover to a marble head and to change the image of one emperor you didn’t like into that one you did.”

But the sheer number of monuments under attack, whether toppled or defaced, is cause for reflection not only on the symbolism of these giant hunks of stone and metal but on the aesthetics. Anyone who has studied art history knows that the equestrian monument—simply, a hero on horseback—has been around centuries, and there are stirring examples by major artists like Donatello and Verrocchio. But by the time we get to Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s memorial to General William Tecumseh Sherman, mounted on his steed behind a winged figure of Victory at the south end of New York’s Central Park, the idea was already beginning to wear a little thin. (As one wit, sympathetic to the Confederacy, remarked: “Isn’t that just like a Yankee to ride on horseback and make the lady walk.”)

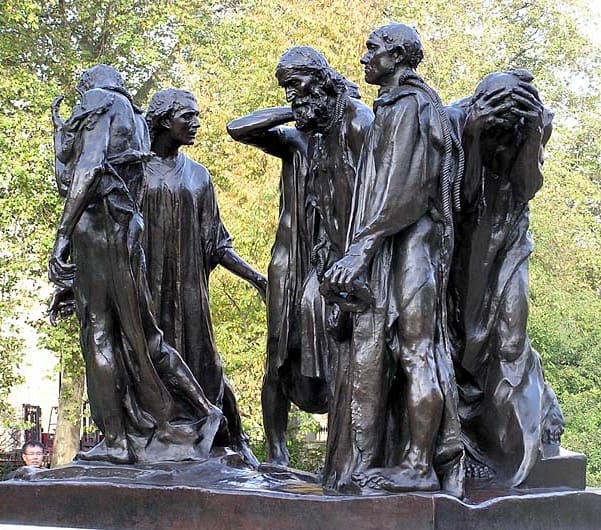

If I recall my art history correctly, public monuments of this ilk were already losing favor in Europe in the 19th century. Decades of revolution made it clear that the statues were the first to go when an army invaded, and that was perhaps one reason Rodin’s stirring Burghers of Calais (at top) earned the approval of the committee that commissioned the work. Intended to be placed at ground level, rather than on a pedestal, the monument celebrates six townsmen who gave their lives to prevent a siege by the English in 1346. They are presented not as positive images of sacrifice, but instead convey anguish, terror, and resignation. Rodin wanted them at eye level so that spectators could almost bump into their emotions.

Now why, you may ask, can’t more artists bring that level of imagination to monuments intended to celebrate heroes or events, whether noble or godawful? Possibly because good artists don’t go after these commissions, and when they do, they can suffer a scathing response. Witness Eric Fischl’s Tumbling Woman, made in homage to those who fell to their death from the towers during the attack of 9/11. When she was placed on the concourse of Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan, the public outcry was so vehement that the sculpture had to be removed within a week.

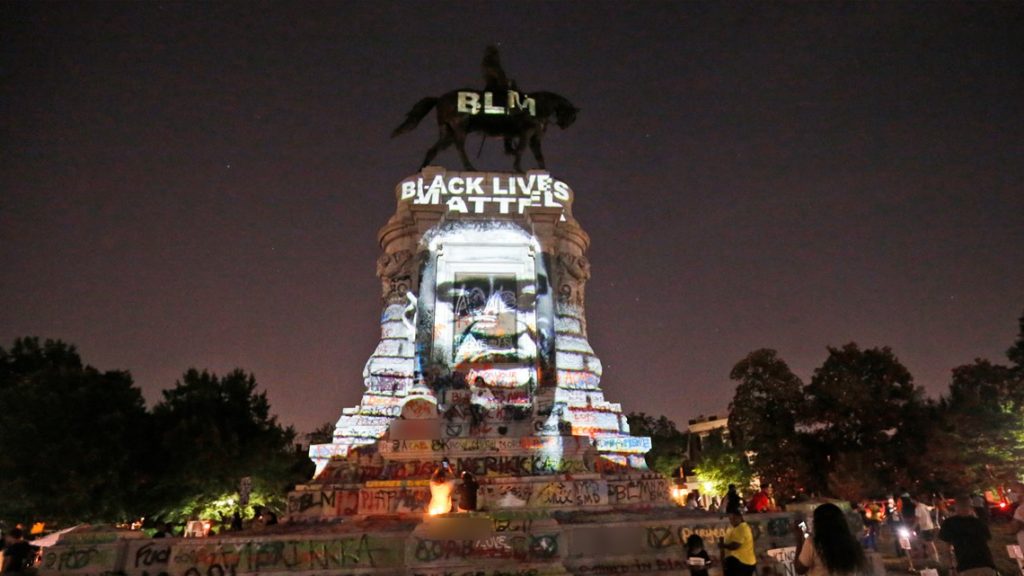

Still, maybe the attacks on so many tributes to racist villainy will force us to rethink what public art should look like. Already there are hopeful signs. A moving, ghostly image of George Floyd was projected on a monument to the Confederacy in Richmond, VA. Banksy revealed a sketch for a work (in what medium it isn’t clear) that would show four protesters pulling down the statue of slave trader Colston. And an Ácoma artist, Maurus Chino, told the New York Times “that in his view, removing the monuments did not go far enough. ‘Melt them down and recast them as commemorative pieces,’ said Mr. Chino, adding that doing so could help draw attention to crucial junctures in New Mexico history, such as the 1680 uprising that figured among the most successful Indigenous rebellions against the Spanish empire anywhere in the Americas.”

I like that idea. In earlier times, bronze from reviled monuments got melted down for bullets and cannonballs. Let’s figure out a way to collect all that expensive material, bronze and marble, and hand it out to artists of color—or any artist with a good idea for monuments that might replace all those toppled tributes to villainy. It’s an expensive proposition, I’m sure, but probably far less than the $40 million taxpayers have paid to preserve Confederate monuments and sites, as Smithsonian magazine reported two years ago.

I, for one, would be very happy to serve on a committee that doles out the goodies. Maybe Joe Biden will give me a job.

In the New Ways to Reconceive Old Monuments category, another project that’s worthy of mention is Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Monument in Madison Square Park, which opened a few weeks before the pandemic hit NYC. He projected the stories of resettled immigrants onto the statue of Admiral Farragut. It was totally brilliant, and moving. Another great Brooke Kamin Rapaport project. I thought of it the other day when I was in the park with a friend, who pointed to the monument a bit disparagingly and wondered what it was all about. I realized that because the project went up in January, and the city was on lockdown while it was still happening, that many people may not have gotten the chance to see it.

https://www.madisonsquarepark.org/mad-sq-art/krzysztof-wodiczko-monument

Love this article. A jaunt through the history of monuments was a great read this late afternoon. The suggestion of melting down and reusing bronze & re-purposing marble for contemporary sculpture by artists of color and others would be an amazing way to begin to right old wrongs. It would incorporate recycling into the mix, an environmental statement. Plus an opportunity to educate the public about why powerful, moving, beautiful artwork would be a fitting replacement for bad and vile old monuments. I vote for you to be on the committee if this ever happened!