By Jane Barthes

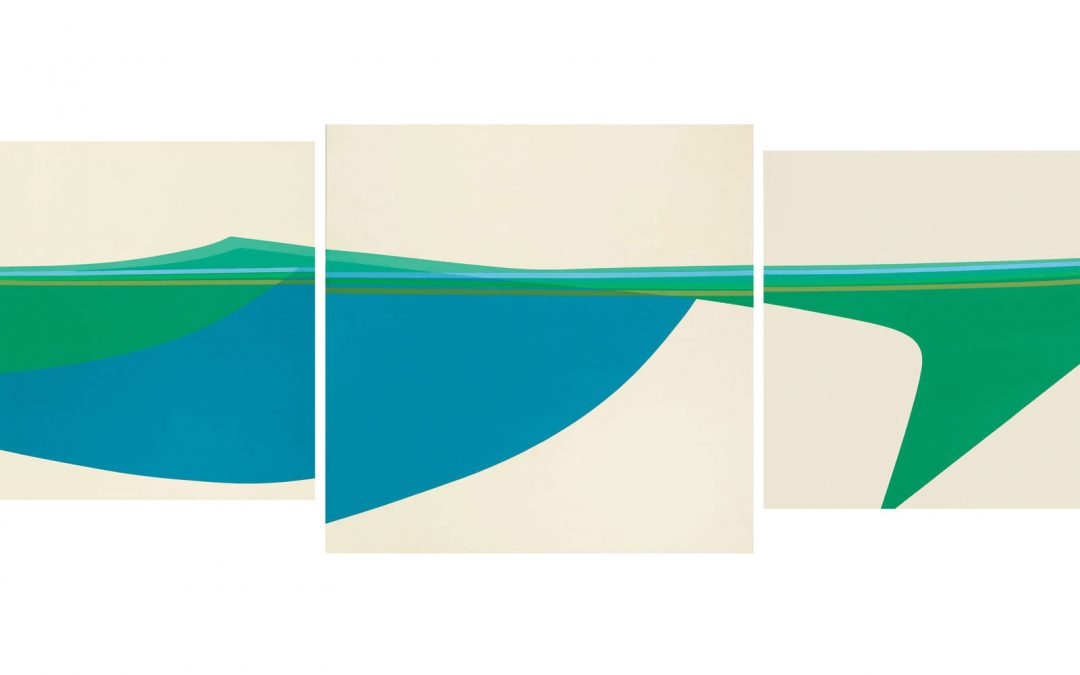

As an artist originally from Europe—and one whose own path did not begin with abstraction—I confess I possessed a rather rudimentary knowledge of geometric abstraction, particularly American hard-edge abstraction. It was at Art Expo in Chicago in 2015 that I stumbled across Helen Lundeberg’s work for the first time. I had been trawling the usual mix of booths, but nothing had really caught my attention until I spotted Lundeberg’s monumental Triptych from 1963 at the Louis Stern Fine Arts booth from West Hollywood, CA. I settled on a bench facing the booth to contemplate the piece, utterly captivated by the rigor, restrained use of color, and handling of the illusion of space through flat geometric shapes that rhythmically appear to recede or move forward on the canvas. As I sat there for some time, a willowy, tanned woman from the booth approached and pressed me to accept a beautiful catalogue of the gallery’s “ongoing re-exploration” of the painter Helen Lundeberg. I only then noticed that the entire booth was devoted to a selection of Lundeberg’s paintings spanning her career. I was in heaven. My education had begun!

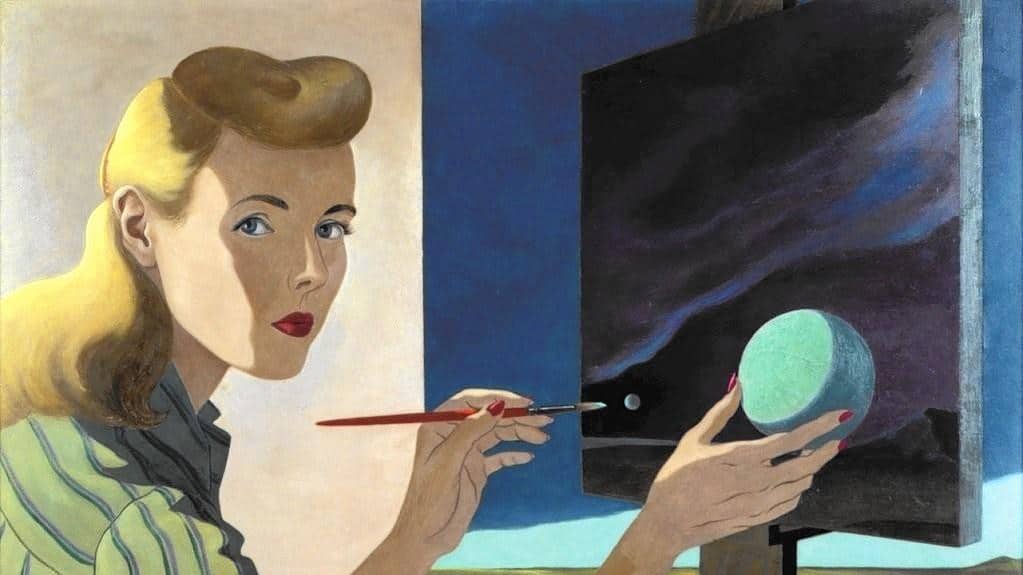

Lundeberg was born to Swedish parents in Chicago in 1908. Her family moved to California in 1912 where she grew up, an avid reader with aspirations of becoming a writer. It was not until she was 25 years old that she settled on her path as a painter. In 1930, after graduating from college, Lundeberg enrolled in art classes at Stickney Memorial School of Art in Pasadena where she met the professor and painter, Lorser Feitelson, who later became her husband. During the 1930s and early ‘40s, Lundeberg worked in a Social Realist style. Both Lundeberg and Feitelson were credited with establishing the New Classicism/Post-Surrealist Movement in 1933, which comprised a loose group of artists such as Philip Guston, Grace Clements, and Harold Lehman. Lundeberg conceived the New Classicism Manifesto in 1934 as a response to European Surrealism. Unlike their European counterparts, who depended on dream imagery, American Post-Surrealists carefully planned the concrete subject matter of their paintings through which the deeper meaning is conveyed to the viewer.

By the middle of the 1940s, Lundeberg also distinguished herself, not only as an esteemed woman artist but as one of only three women artists in Southern California to be making large public art pieces for the Works Progress Administrations Federal Art Project. Many of these murals are now considered lost, destroyed, or simply painted over as the buildings have been repurposed but the History of Transportation in Inglewood, CA, is, of late, fully restored and the preliminary drawings are held in the permanent collection at the Nevada Museum of Art.

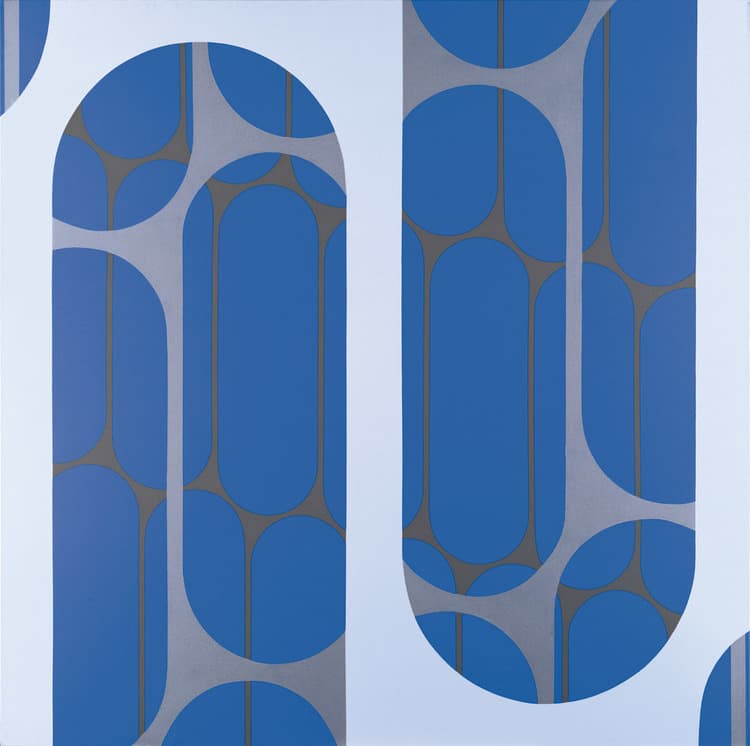

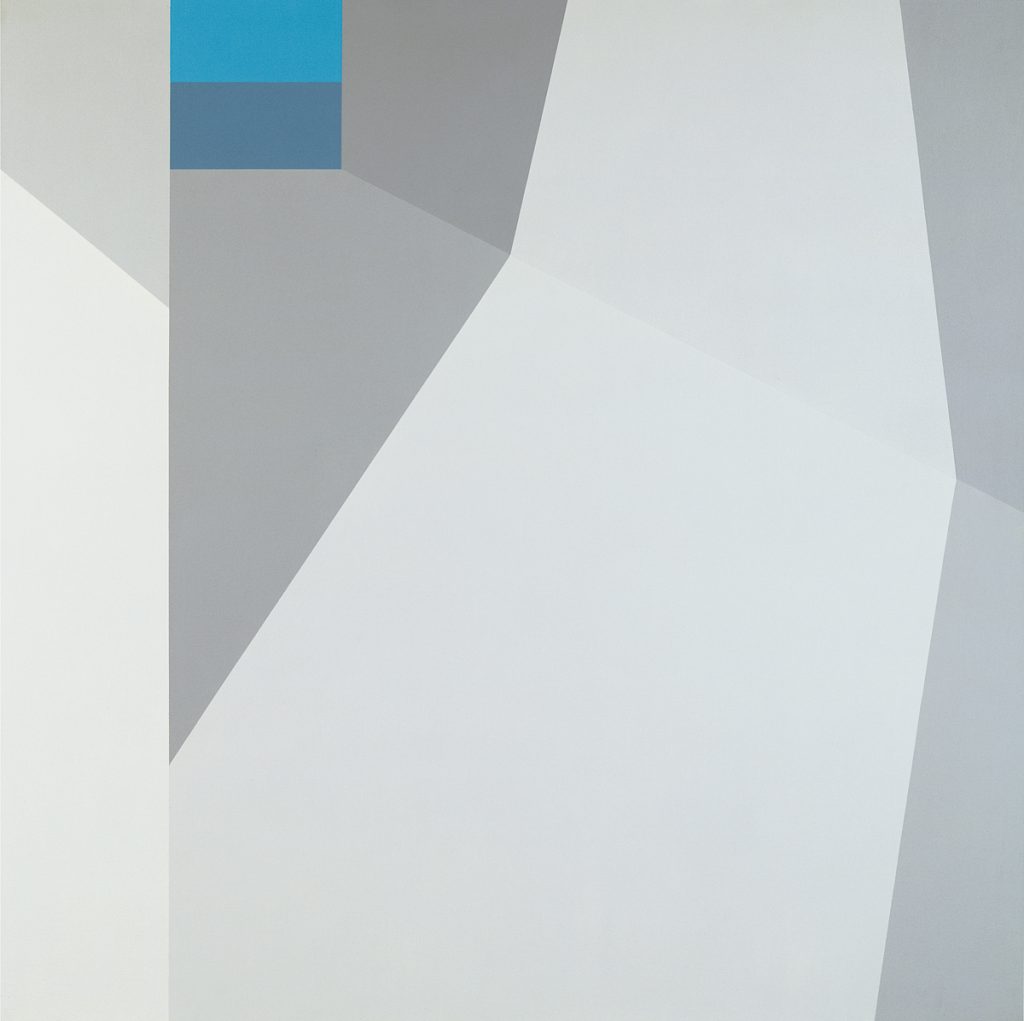

It was not until the 1950s that Helen Lundeberg decisively began to move away from representational work and into hard-edge abstraction, a style in which she was prolific throughout the next thirty years, (from the 1960s through the ‘80s) as she explored architecture, landscapes, interiors, still life and planetary forms. Her architectural works were notably inspired by her love of 15th-century Italian primitives, precursors of the early Renaissance. Her last known work, Two Mountains, was completed in 1990 and she died in 1999, aged 91.

Helen Lundeberg was an esteemed painter during her lifetime. Some might argue this was in part because of her connection with her husband, but that only serves to minimize her strong, unique vision that communicated itself through evocative spatial constructs, a deep sense of poetry, rhythm, and an ability to convey emotion with an understated palette. Her compositions are honed and whittled to the essential visual necessities. As Marie Chambers wrote in her essay about Lundeberg in the catalogue from Louis Stern, “Infinite Distance Architectural Compositions,”: “The artist delivers an entirely delicious experience of looking through things.” I would agree with Chambers in her conclusion that “Ms. Lundeberg is simply inspirational.”

Jane Barthes is an artist living in Chicago. A profile of appeared in “Under the Radar” in December, 2015.

Top: Helen Lundeberg, Triptych (1963), acrylic on canvas, 60 by 204 inches

I love reading artists writing about artists/ art that grab them. Thank you Jane for this piece – clear and evocative and work I had not encountered before.

Wonderful to discover an exciting artist hiding in full view, not more widely noticed perhaps because she was a woman. Thank you Jane for leading us to her. Seeing her through your eyes I can sense the monumentality of the pieces even when they are not very large , the movement back and forth of the shapes in space and the sheer beauty of the paintings.