“Cameras and photography have been in my DNA since I was about 10 years old,” says Stephen Robeck. “The mystery is that I don’t even know why or how it started. I’d go and take pictures with a simple little camera, develop them, and make prints.”

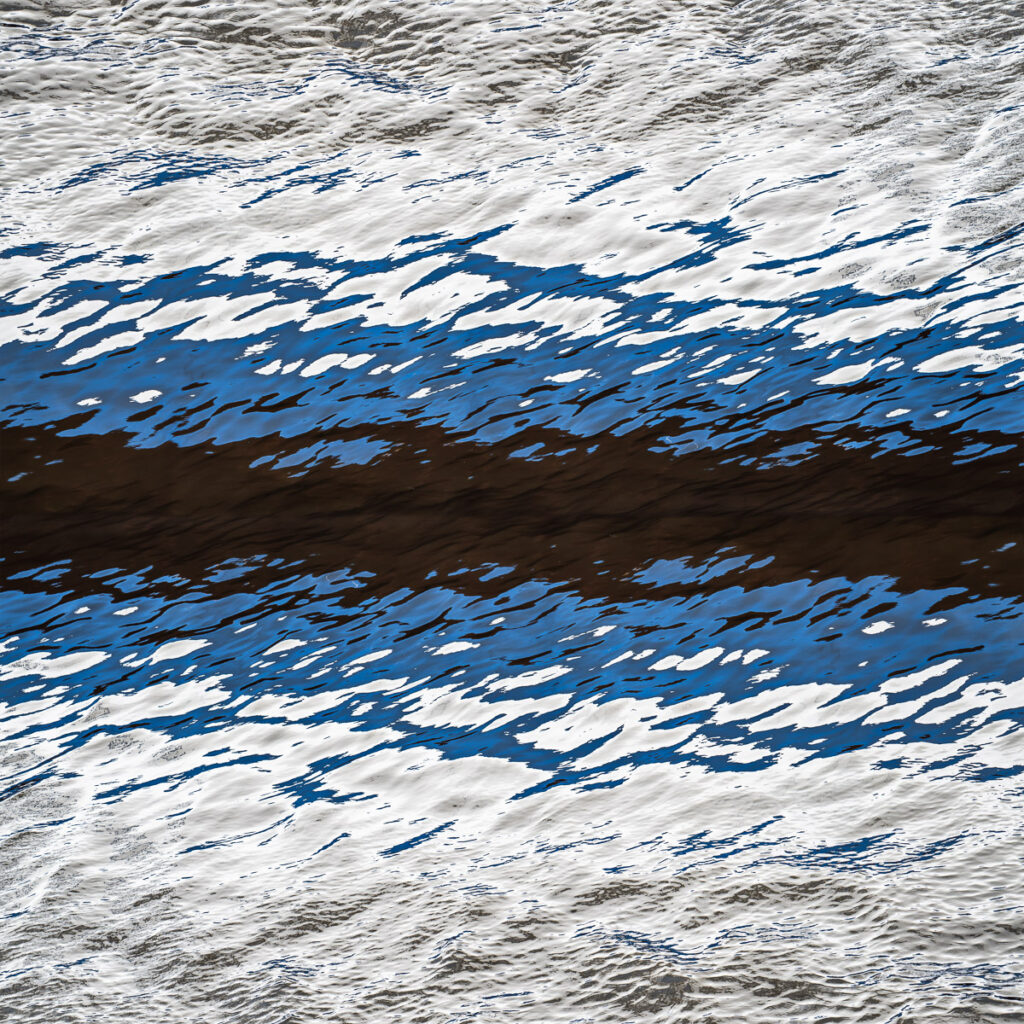

After a career spent in commercial photography and “creative marketing”—which meant manufacturing promotional toys based on characters from the big film companies —Robeck had his moment of truth on backpacking expeditions in the High Sierras. Like legions of others, he could take picture-postcard views of the majestic surroundings, but over time he found himself attracted to the abstract aspects of nature: the mesmerizing patterns of water, the textures and subtle colors of tree bark seen up close, or the voluptuous shapes realized by wind and weather in desert sands.

The upshot is a very painterly and sensuous vision of phenomena we encounter every day, whether it’s on a walk through the park or a trip to the beach. Though Robeck has ventured into Death Valley for a series of works, the impact of his photos does not depend on the exotic nature of the locale; if anything, his abstractions demonstrate that the exotic is right in front of us, if we choose to look carefully.

And though his work appears spontaneous, the result of a single capture, many of his images are “composite photographs,” which sounds a bit like cheating but is no more duplicitous then mapping out a fresco to transfer an image from a drawing to the wall. It sounds, in some cases, a whole lot more laborious. Robeck explains:

“Eucalyptus 370° and Ponderosa Pine 370° are each made from about (they vary) a dozen vertical captures taken while moving around the circumference of the tree,” he writes. “The individual elements are first arranged to achieve the desired end points where you see a visual detail repeated, thus the 370° in the titles. Then the elements are positioned, masked, and painted to create seamless blends. This is tedious work, but if the captures are good (same height from the ground, distance from the tree, etc.), the illusion is very convincing. This is partly because of the extreme level of detail, even in a print almost six feet wide, that results from combining a dozen 25- to 40-megapixel captures.”

The illusionism is heightened by Robeck’s method of finishing and framing the images. Several years ago he dispensed with glass, because the reflections are so distracting, and arrived at a way to make archival-quality prints (meaning they’re good for 100 years or more), which he floats in a simple wooden frame. He uses a slightly textured watercolor paper called Somerset Velvet, so that, he says, “Even the faintest reflection of sunlight is diffused. The result is colors that jump off the print and a three-dimensionality that’s truly surprising.”

For more information on the photographer and his works, please visit https://www.sprimages.com/