I fell down the rabbit hole with Woody Allen last week.

Blame it on Google and Kate Winslet. I am often, in the wee hours, trolling something on the Big G called “stories to read” (well, what else are they for? They’re online; you can’t use them to line the litter pan). Google knows that I like news about the art world, recipes for Italian food, and occasional tidbits on Ivanka and Meghan and Harry. (The Big G has probably also surveyed the contents of my closet and knows I covet Kamala’s sneakers.)

But approximately ten days ago I spied a story about how Kate Winslet in a Vanity Fair interview was lamenting that she ever worked with Woody Allen. And I said, “Hey, wait a minute, Katie, your last movie with Allen was three years ago, Wonder Wheel, and it was something of a bust.” By then news of the alleged abuse of his adopted daughter, Dylan, had been kicking around for 25 years, revived in 2018 when Dylan had a teary interview with CBS news and most recently when Ronan Farrow, another adopted child, successfully fought Hachette to suppress Allen’s autobiography. Winslet also had a chance to air any moral conundrums when she talked to the media to promote the film in 2017.

Normally I am not much intrigued by celebrity brouhahas, but Woody Allen has been in my cultural orbit from a young age. I’d never been a big fan of his comedies, but as a long-time New Yorker, still in graduate school, I saw Annie Hall along with many friends, and realized it was a kind of breakthrough in moviemaking: characters were talking about “relationships,” not love; they were seeing therapists and sorting out sexual incompatibilities. Just like us. Diane Keaton was adorable, and it was a film full of memorable moments (one of my favorites was Jeff Goldblum hoarsely whispering into the phone: “I forgot my mantra!”)

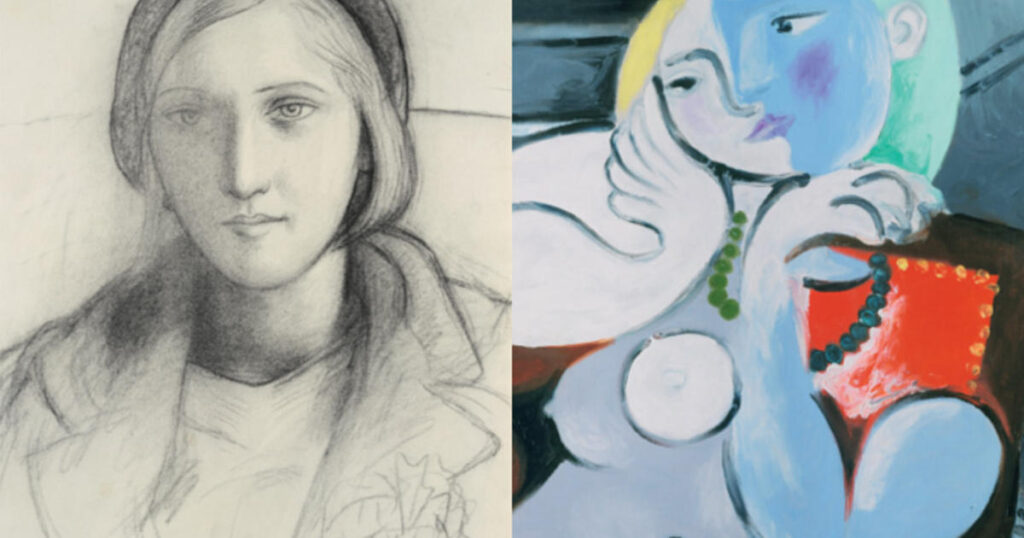

Marie-Thérèse Walter was four years younger than Soon-Yi Previn when Picasso bedded her. She later committed suicide.

I’ve loved many of his movies down through the years—Crimes and Misdemeanors, Match Point, Midnight in Paris, Blue Jasmine—but would concede there were quite a few clunkers. Still the guy has made more than a movie a year since 1965, for a total of about 67 in all. Does this make him an artist, a great artist? For sure he is an auteur, in complete control of his stories and their production. How heinous were his transgressions against the family? And here is where we come back to the artist part: Why do some get singled out for punishment and a giant like Picasso goes off relatively scot free?

But first let us briefly review the Farrow-Allen debacle, a tortuous saga that makes the House of Atreus look like The Brady Bunch. Mia and Woody, lovers in a 12-year relationship, adopted Dylan and Moses, and had one biological son, Satchel (now known as Ronan Farrow, who famously chronicled the misdeeds of Harvey Weinstein and others, but whose reporting has also been the subject of criticism in The New York Review of Books and The New York Times). Mia Farrow, the daughter of actress Maureen O’Sullivan, has 11 living children, four of whom are biological and seven adopted, and has been married to Frank Sinatra and composer Andre Previn (two of her adopted children died, one an apparent suicide).

Woody Allen fell in love with Mia’s adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, who was 21 at the time he took nude photos of her and left then on a mantelpiece in his New York apartment, where they were discovered by Mia on a visit (even the over-analyzed Allen admits this was a Freudian fumble). Two years ago, in a controversial interview with Daphne Merkin for New York magazine, Soon-Yi detailed all manner of abuse at the hands of Farrow, including pelting her with toy blocks and holding her upside down by her feet so the blood would flow to her head to make her smarter. Soon-Yi married Allen in 1997, and they have two adopted children together. It appears to be a happy and supportive union.

Eight months after finding out about the affair between Soon-Yi and Allen, Farrow accused Allen of sexually molesting their mutually adopted daughter, seven-year-old Dylan, in the crawl space of an attic in her Connecticut home (I had to look up “crawl space” to see just how small an area this generally is). Dylan alleged that he touched her “private parts” (later expanding that to mean her labia and vagina). According to Wikipedia, the Connecticut State’s Attorney investigated the allegation but did not press charges; the Connecticut State Police referred Dylan to the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale–New Haven Hospital, which concluded that Woody Allen had not sexually abused Dylan; and the New York Department of Social Services found “no credible evidence” to support the allegation.

So why is this bombshell being kept alive? Frankly, I don’t know and at this point find the whole controversy exhausting. But doing the research led me to watch a few Allen movies again, along with a two-part documentary in which no mention is made of the molestation charge and its dismissal. After about 20 minutes, I nixed a couple, like Wonder Wheel and the much ballyhooed Manhattan, because for different reasons they annoyed me. But I was enthralled all over again by the chilly class-conscious storytelling of Matchpoint and thoroughly charmed by the romantic mishaps in Hannah and Her Two Sisters.

Which brings us in a very roundabout way to Pablo Picasso, because I was trying to remember if the colossus of 20th-century art was ever so repeatedly condemned or his works removed from circulation for bad behavior. As detailed three years ago in a review of a show of the master’s drawings at Gagosian, critic Cody Delistraty wrote (to sum it all up): “After Jacqueline Roque, Picasso’s second wife, barred much of the family from the artist’s funeral, the family fell fully to pieces: Pablito, Picasso’s grandson, drank a bottle of bleach and died; Paulo, Picasso’s son, died of deadly alcoholism born of depression. Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s young lover between his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, and his next mistress, Dora Maar, later hanged herself; even Roque eventually fatally shot herself. ‘Women are machines for suffering,’ Picasso told Françoise Gilot, his mistress after Maar. After they embarked on their affair when he was sixty-one and she was twenty-one, he warned Gilot of his feelings once more: ‘For me there are only two kinds of women: goddesses and doormats.’ Marina saw her grandfather’s treatment of women as an even darker phenomenon, a vital part of his creative process: ‘He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, and crushed them onto his canvas. After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.’”

If Picasso were alive today would the #MeToo movement be clamoring for his head on a pike? Undoubtedly. But I would wager that the next Picasso show at Gagosian or any museum will not bring up the subject of collateral damage in the artist’s family. (A cursory survey of reviews of the Royal Academy’s blockbuster “Picasso and Paper,” which closed in August, contained nary an allusion to suicides, neglectful parenting, or other unsavory aspects of the artist’s personal life).

But if Woody Allen wants to distribute a new movie, well, watch out. His latest, Rainy Day in New York, was dropped by Amazon and has been, as far as I can tell, repeatedly postponed for release in the U.S.

Perhaps history will be kinder.

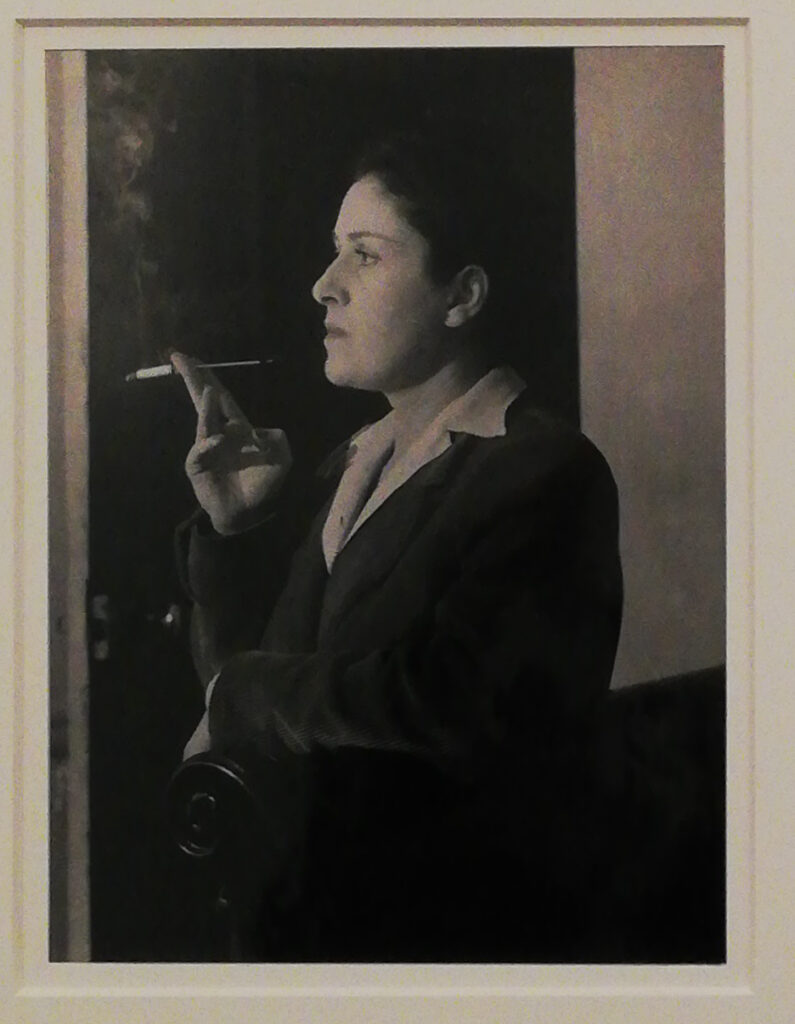

Top: Woody Allen and Soon-Yi Previn in Venice