The answer these days is far from simple.

The late, great, often cantankerous art critic Robert Hughes more than once bemoaned the apparent decline in standards for draftsmanship. “In the 45 years that I’ve been writing criticism there has been a tragic depreciation in the traditional skills of painting and drawing, the nuts and bolts of the profession,” he told members of London’s Royal Academy of Art in 2004. He added, almost paradoxically, that “drawing never dies, it holds on by the skin of its teeth, because the hunger it satisfies—the desire for an active, investigative, manually vivid relation with the things we see and yearn to know about—is apparently immortal….”

I couldn’t agree more with the latter part of his sentiments, but on the question of the first, I think Hughes was grievously mistaken. There are still plenty of artists who can do Old Master-ish portraits and academic life studies, who have learned all the tricks and twists of line and shading and highlighting. But they are generally not the ones who are doing the most interesting or challenging work in the medium we think of as drawing.

If Hughes, who was notoriously hostile to most contemporary art, were still around today, if he could cruise around the members of this site, he would see that drawing is still very much alive among artists, but the definition of what makes a drawing a drawing has expanded. And the ways in which artists approach drawing can be radically different, as are the ends they arrive at.

The Traditionalists

In the Renaissance—much as we may value the glorious sketches of Michelangelo or Tintoretto—a drawing was seldom thought of as an end unto itself. Most often it was a study for a painting or a sculpture. Realized on a sheet of gridded paper, figures outlined in crayon or charcoal could be more easily transferred to a wall as frescoes. That attitude toward drawing as a kind of “floor plan” for bigger and grander things seems to have persisted well into the 19th century (with the exception of visual satirists like Daumier and Horace Vernet). Then, perhaps beginning with the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists—with Degas’ pastels and van Gogh’s pen-and-ink landscapes—drawings began to take on a life of their own.

But among those members of the site who may seem most traditional in their approaches, sketches toward an end product are not as easy a match-up as, say, Leonardo’s breathtaking silverpoint study for the angel in The Virgin of the Rocks and the final figure in both versions of the painting. For his painting The Wave, a work made entirely from his imagination, Christopher Benson did several preliminary sketches, “otherwise [the painting] would never look right,” he says. And the final color sketch involved a complex process done in Photoshop by “layering a scan of the final oil sketch under a transparency of sampled scans from several other earlier seascape pictures.”

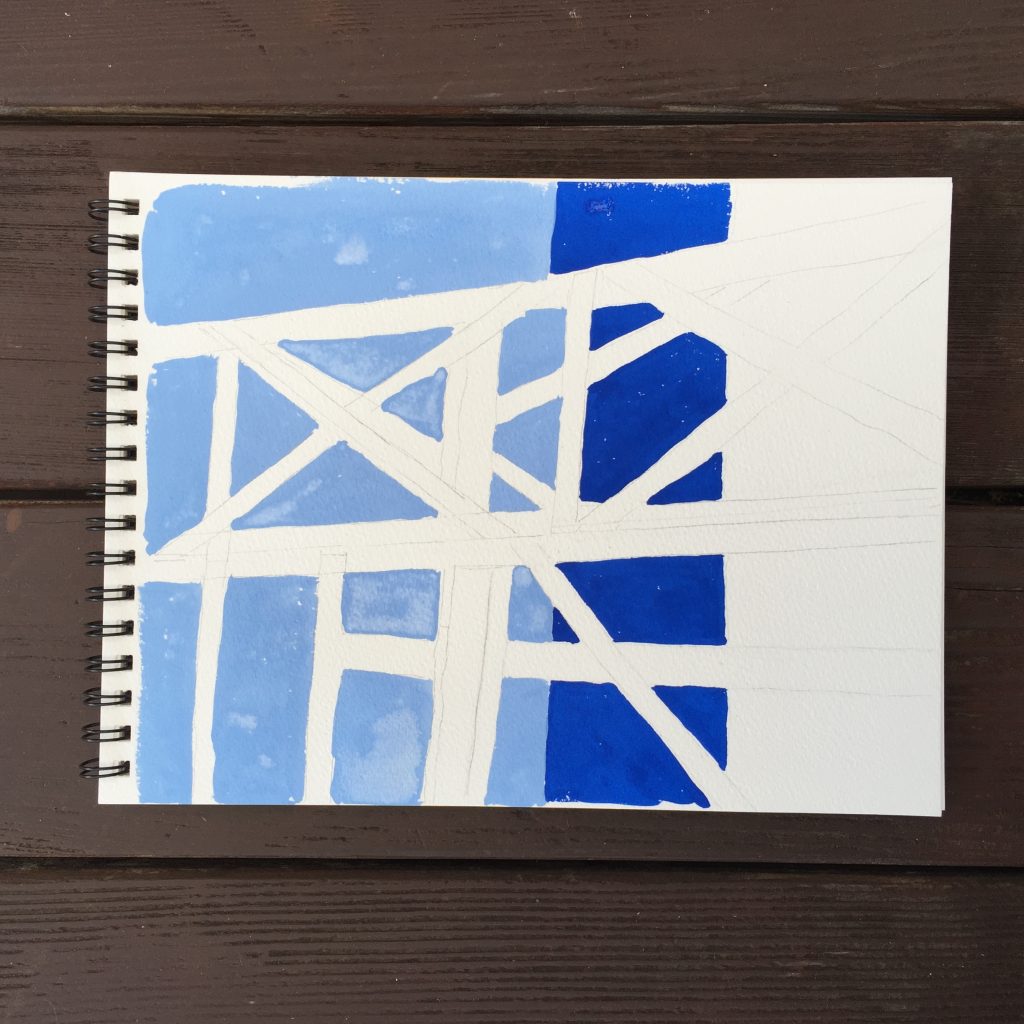

Mitchell Johnson’s paintings of cities and seascapes depend heavily on severely abstracted geometries, and so he says he draws “on the canvas or watercolor paper to be sure the shapes are in place the way I want. I’m very concerned with how I get to the edges of the square or rectangle and always have been.” Drawing, he says, “is about capturing energy and rhythms and space within the picture plane. Sometimes the drawing is very interesting, but the strength is lost when the color is applied. The drawing should have been left alone. It was a finished work without the color.”

David Herd, a Scottish painter whose portraiture sometimes seems an update on forebears like Gainsborough or Reynolds, claims you “can make a successful image with ‘bad’ drawing.” Sometimes, he says, he draws meticulously onto a surface before he starts to paint, but the “drawing is very often eradicated completely and replaced with the drawing of paint, where I still consider what I do to be a form of drawing but with larger marks and hue and value included.”

Drawing or Painting: What’s the Diff?

As Herd implies, more than a few artists no longer see that big a division between drawing and painting. Lanny DeVuono, who studied with Jay DeFeo years ago, says: “When people make a distinction between drawing and painting, I am often a bit confused. I approach drawing in a layered fashion, employing gesso again and again, recreating various grounds for graphite. So in that sense my drawings end up looking like paintings. I also use gouache in the gesso to add pigment, and sometimes I use acrylics and even oils. I use graphite powder, mixed with alcohol or even water, with a rag or a brush. I use graphite sticks from the side to get wide textural marks, and mechanical pencils for tiny, tightly articulated lines.

Lanny DeVuono, OS8 (2015), graphite, gouache and gesso on wooden panel, 30 x 30 inches

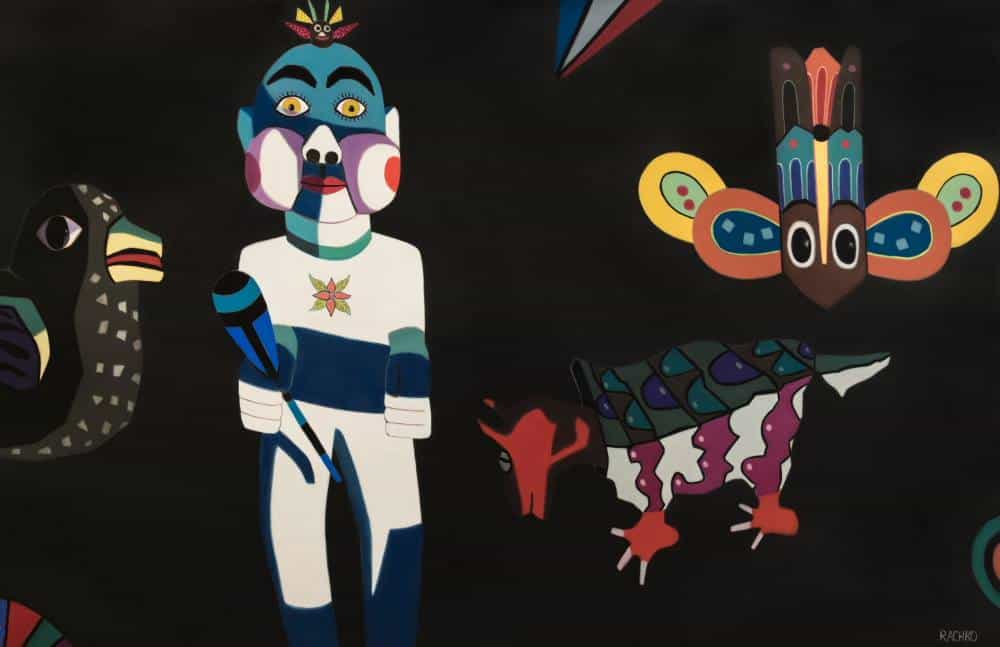

A museum curator or art historian would most likely classify a work made with pastels—which are after all basically colored chalk, generally in stick form—as a drawing. But “among artists who work in pastel, these two words have a very specific meaning,” says Barbara Rachko. “For a pastel artist, a ‘drawing’ refers to a work in which the paper or other substrate is allowed to show through. In a pastel ‘painting,’ you do not see the substrate at all—i.e., pastel is used much more heavily in a painting than in a drawing. Since I have always spent months on each piece, covering the entire sandpaper ground with up to 30 layers of pigment, I have always considered my work to be pastel painting.”

Storytelling and Diaries

Linear motifs of one form or another, used to convey a message or provide a narrative, are probably the oldest forms of drawing, and in spite of Modernist and formalist dictates that contemporary artists should expunge all such impulses, the urge to tell a tale nonetheless persists. Leslie Kerby worked in museums and briefly had a wholesale line of cards before she learned printmaking and discovered that what she really wanted to do was offer up a story. “There was an evolution from cards to drawing figures,” she says, “and what interested me about both was creating some kind of narrative for my work.” Her gentle satires have taken on the medical profession and the problems of public housing. Kerby’s most recent series. “Containments,” is far more abstract than her earlier work, though still with a social message, exploring the uses of shipping containers for permanent low-cost or temporary housing, or as vessels for risky passages to freedom. But drawing, she says, “Is still an essential thread. You need to draw a line with a beginning and an end. It gets you from one place to another, and I think of it as having a kind of journey.”

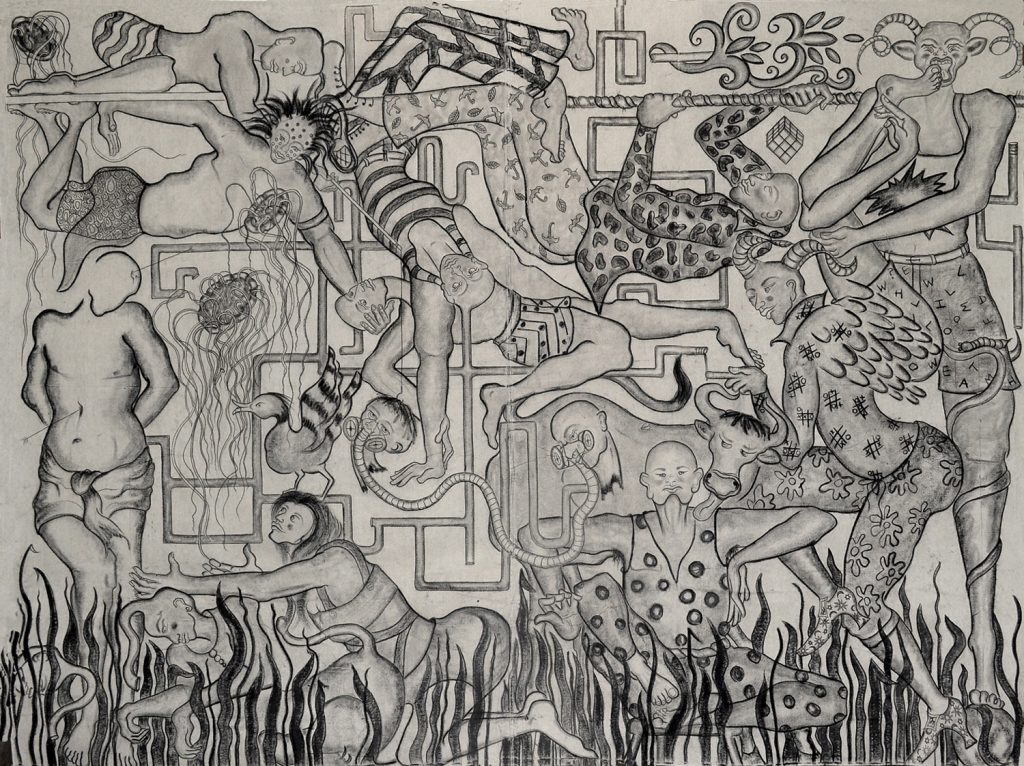

Amita Bhatt’s large-scale drawings, as big as nine by twelve feet, also give rein to a storytelling impulse that frequently focuses on “man’s basest nature—inflicting violence,” she says, adding that drawing in charcoal has a primacy that seems best suited to the subject matter. “The size is reverential and forces my audience to be immersed in this dark, cave-like space where the drama of life is played out. It’s like watching one’s own self, one’s own predicaments on this planet with large doses of fantasy. I don’t think painting or film could create this sense of real-time fiction like the charcoal drawings do.”

Amita Bhatt, A Fantastic Collision of the Three Worlds XXIII (2013), charcoal on canvas, 9 by 12 feet

On a far smaller scale, Marc Baseman also creates “stories,” though, like Bhatt’s tableaux, the exact import of his narratives may be obscure. As I wrote in a profile of the artist for the site, his tiny drawings—usually less than three inches on a side—boast a cast of odd characters and objects: birds and rodents, guys in business suits, a naked woman with streaming hair, a kissing couple, crenellated towers, hovering helicopters, space ships, and wide-eyed cats. It’s a universe as packed with as much incident as a medieval miniature, and like a story from long-ago times, the ultimate meaning may be a mystery (but it’s fun to try to guess at it).

Marc Baseman, Splitting (2012), graphite and dry pigment on paper, 2 7/8 x 2 7/8 inches, collection of Tony Abeyta

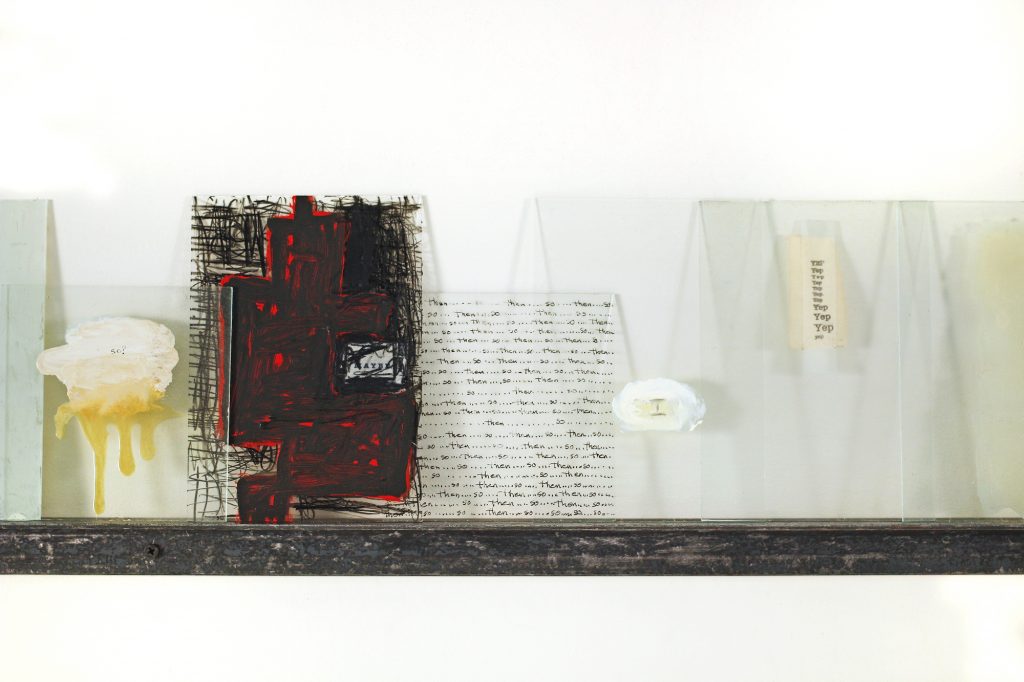

Melinda Stickney-Gibson’s latest “drawings” are on glass panels, each of which contains a mark of some kind. “They’re diary pages,” she says, “Every panel has a different notation that is of meaning to me but it may not come through for viewer. Almost all my work is about human relationships, and making them is therapeutic in a way. They get rid of angst, but they’re not always negative. Her latest work, now at the Cross Contemporary Gallery in Saugerties, NY, as noted in a Vasari21 Update, records “individual, fleeting, but recurring thoughts which are pretty universal to everyone. Doubts, declarations, ‘circular thinking,’ and the ever-present ‘I’ of ego. The fragmented nature of what goes on in our heads, as we go through the day presenting ourselves to the world…and I believe no one is immune to this process.”

Melinda Stickney Gibson, Moments: Thinking (detail, 2016), 19 glass panels, mixed media, 72 by 8 by 1.5 inches

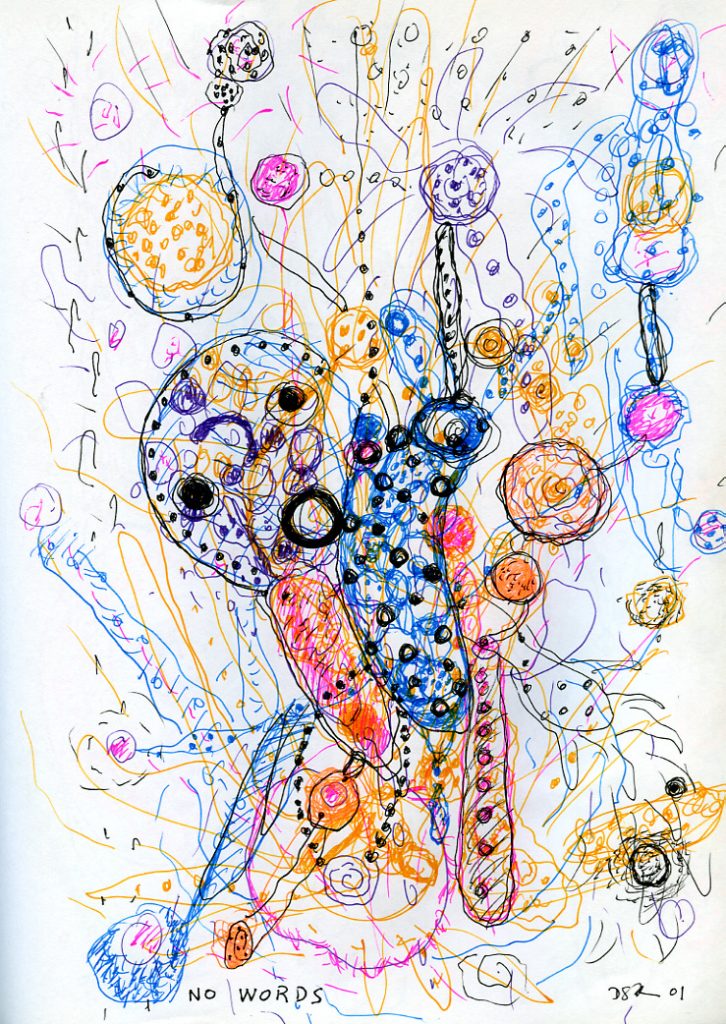

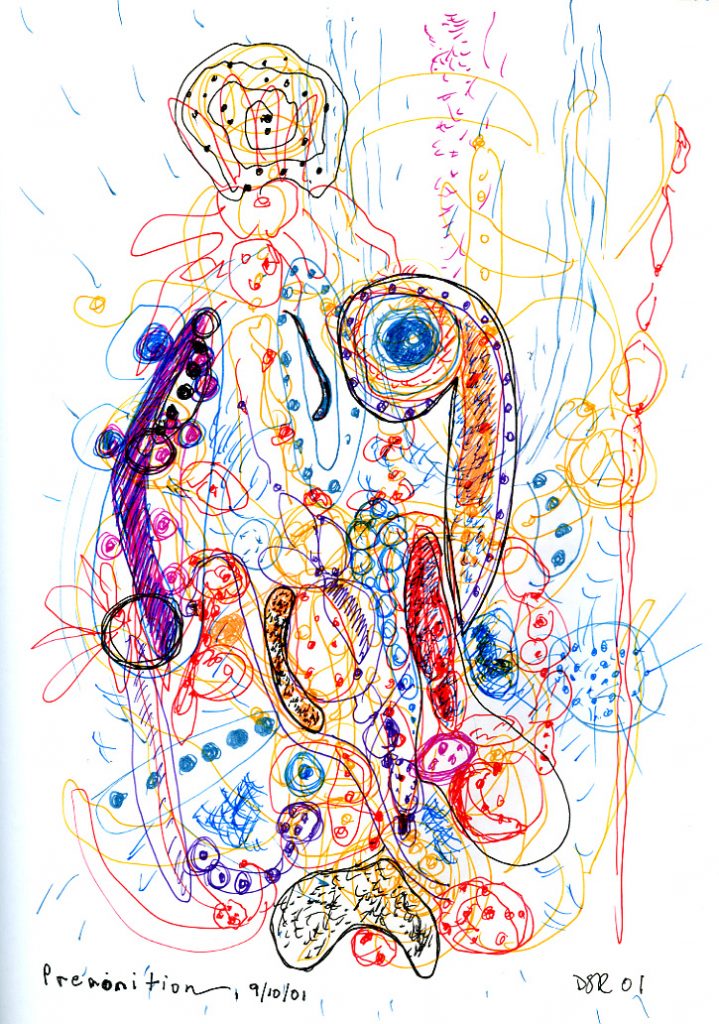

David Rubin, who has had a long career as a writer and curator of contemporary art, started keeping a kind of diaristic journal in the 1980s, influenced by research into automatism and automatic drawing among the Surrealists and Abstract Expressionists. In 2001, Rubin started drawing in his office/studio, because an artist friend bought him a sketchbook with better paper than he had been working on. “On September 10, 2001, I made this really ominous drawing. Then I got a phone call the next day from a friend, who told me about the attacks on the World Trade Center.” The one from the night prior to that horrific event had a menacing aspect; when Rubin looked at another drawing from a few days later, he notes, “I realized I had drawn a kind of variant of Munch’s The Scream. I wasn’t conscious of drawing a face in that imagery, but it showed the emotional response coming to the forefront. Two years later Rubin says he felt he’d found his own abstract vocabulary. “I see it as though I’m stringing beads in a virtual way. I’m making pathways and trajectories in space. To me, drawing is how I commune with the cosmos.”

Though he does not consider his drawings a diary of any sorts, Andrew John Cecil nonetheless puts pen or pencil to paper every day. “If you are lucky, one line is dense with meaning, born of experience,” he says. “The sketchbook has been my constant companion. Since 1979 I have kept a sketchbook. It is the soul of my work. The sketchbook became my studio when I didn’t have a studio. My daily practice as an artist begins with morning drawing, and the drawings often become a point of origin for the development of sculpture.”

Drawings, Nothing but Drawings

A generous handful of artists on the site find drawing a sufficiently fulfilling medium to devote virtually full time to the pursuit. Bhatt, for one, says drawing perfectly suits the themes that most engage her. Marieken Cochius, whose works are now on exhibit at the Holland Tunnel Gallery in Brooklyn (through October 16), says her last ten years have been devoted mostly to drawing. “What I like about work on paper is the immediacy of it. Whatever I do has to be exactly right, because I’m not erasing anything,” says the Dutch-born artist. “Mainly when I draw I get out of my thinking brain, and I use both hands. My left hand is more like an antenna, more searching, while my right hand is more sure.”

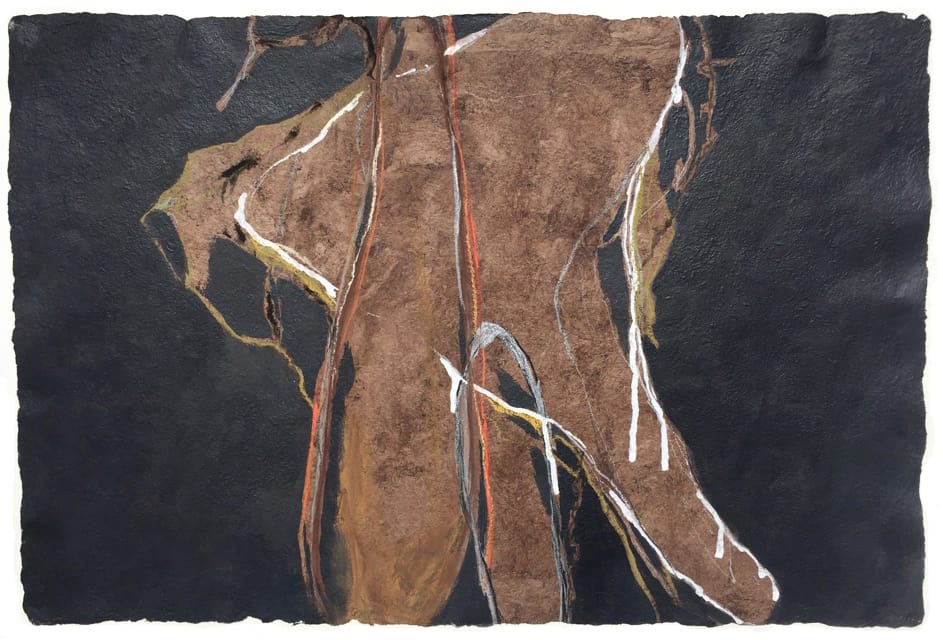

Marieken Cochius, A Space Once Occupied, Now Empty #23 (2016), ink and pastel on paper made of bark, 16 by 24 inches

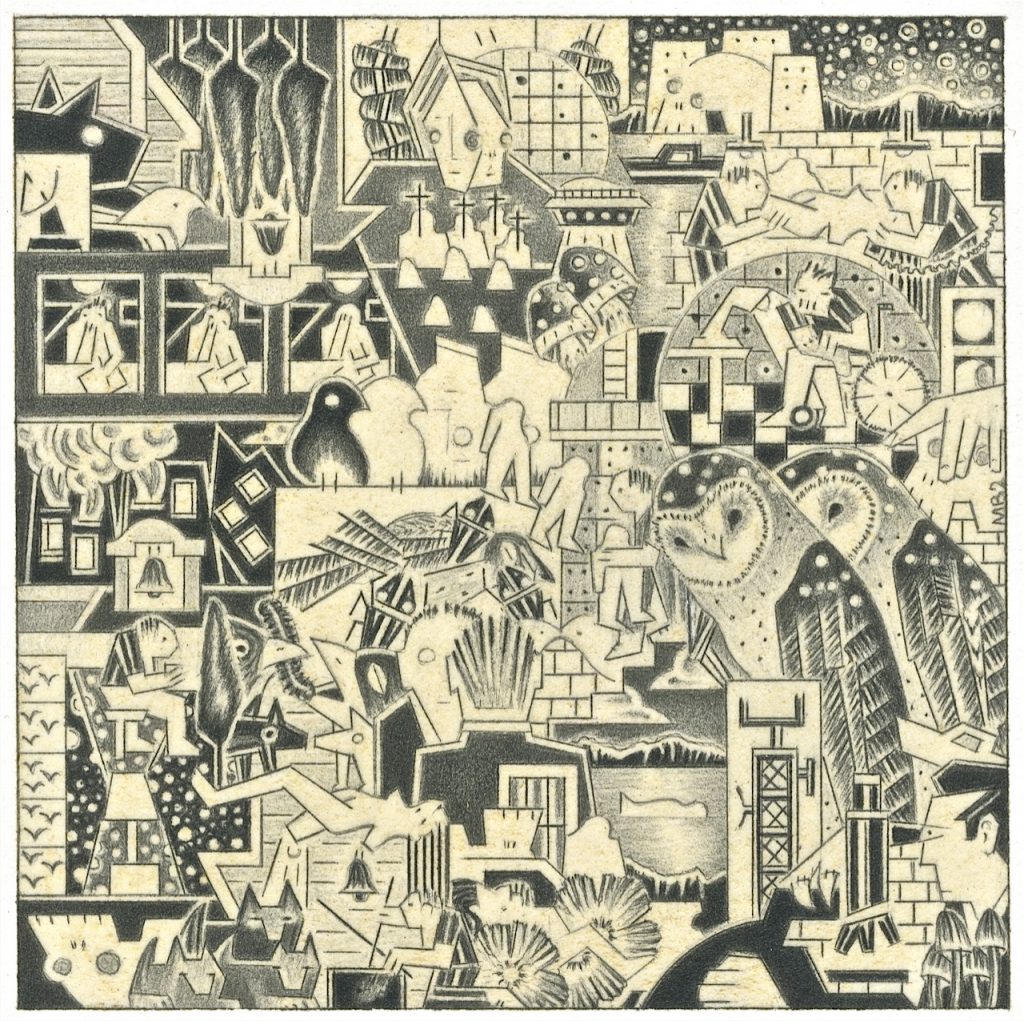

Earlier in her career, Christine Taylor Patten made both paintings and sculptures, but drawing eventually became her sole focus. She works in ink on paper using a crow-quill pen, making images as large as 7 by 24 feet and as small as 2.5 by 2.5 inches. Like Cochius, she uses drawing as a kind of exploratory tool. “I have no idea what I’m looking for. I’m just looking for what I find, and everything has always been in reaction to what I’ve done before. The energy of things happening becomes a drawing—the feeling of the grass out there, the quiet in here. How to get those feelings down on paper. I’m drawing to find the invisible thing that’s happening.”

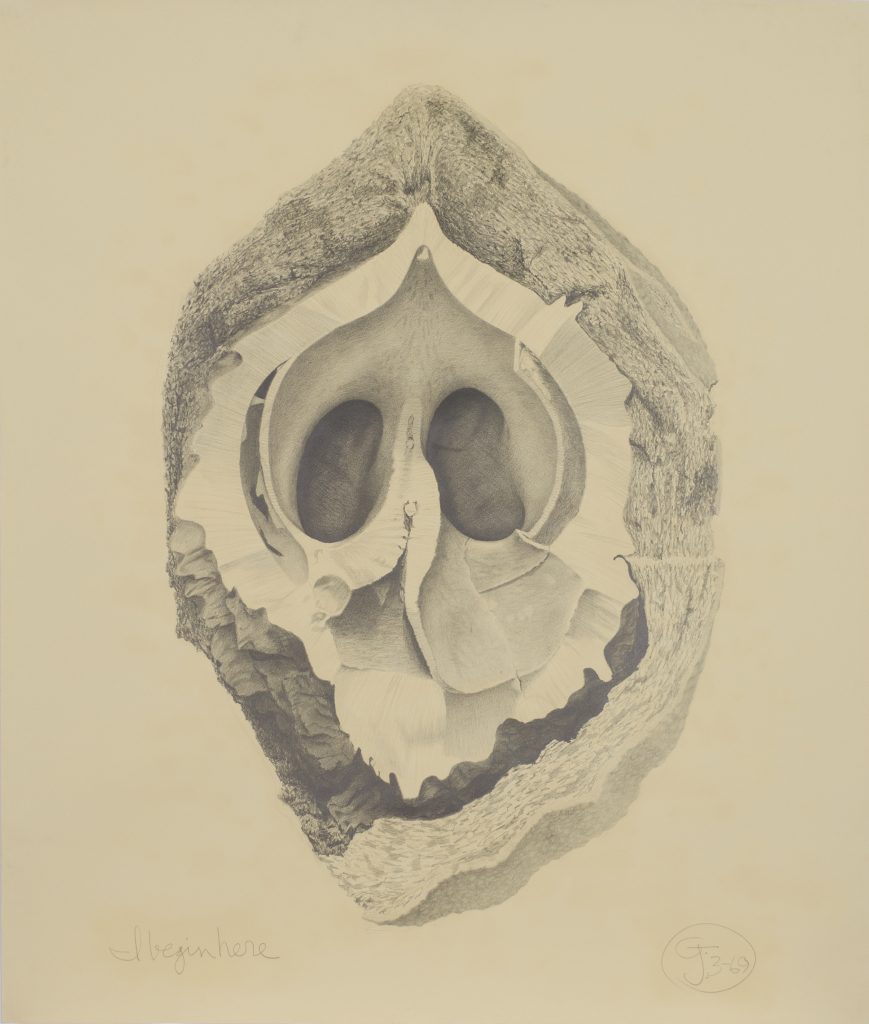

Patten’s husband, Gendron Jensen, has been engaged with drawing, and only drawing, for his entire career. Since his days working in a print shop at an abbey in Benet Lake, Wisconsin, he has been intensely engaged with the remnants of the natural world, most often the bones of animals he finds on “rambles” in the woods and countryside. When he stumbles across these, he says “it’s an apparition to me. Here’s this place where death happened to the creature, and its relics are scattered on the ground. Some of them summon to me, they command me to respond. When I’m really involved in the act of drawing, sometimes an odd thing happens. I suddenly see it hurling from hundreds of thousands of miles away, like a UFO from outer space. I become bound up in this wonderful love life with the object; we become as one.” (A series of 16 of Jensen’s six- by five-foot drawings will be on exhibit at the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee, WI, through December 23).

You Call That a Drawing?

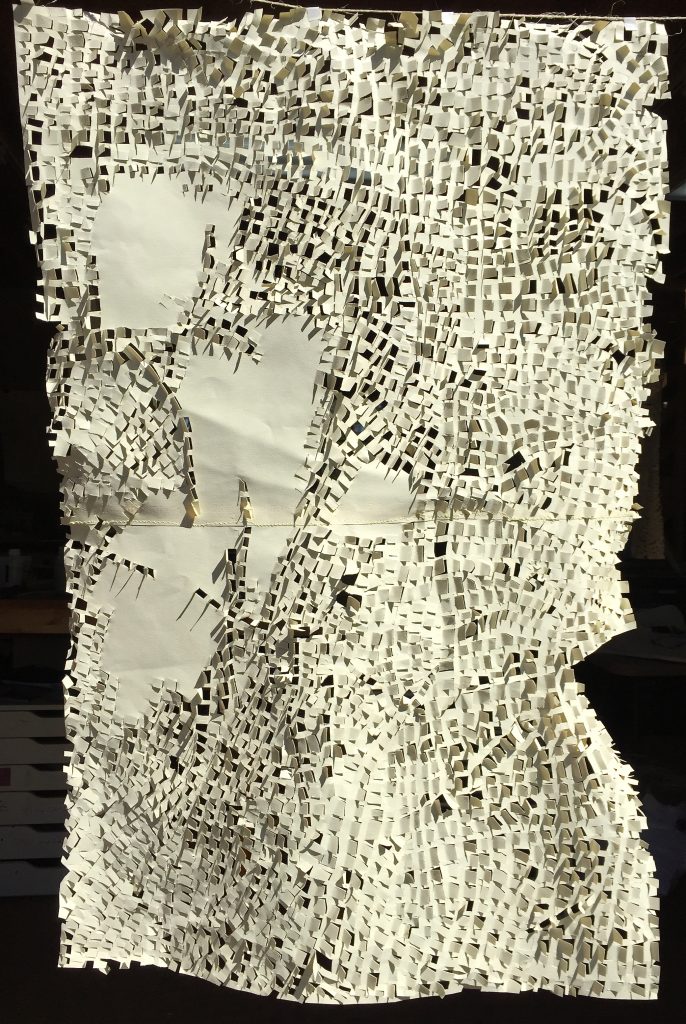

Indeed, Ty Zemelsky does, though her labor-intensive methods may recall other processes, such as cut-paper silhouettes or even tapestries. “Physically I work with rolls of paper and an X-acto knife or scissors, or sometimes an old pair of button-hole scissors. I start at an arbitrary place on the paper and with the tiniest idea, perhaps the shape and size of the first opening and maybe the next one. Each cut is a movement of energy that starts in my feet and goes upward through my spine and shoulder and arm. Each is different from the one before, even in small ways, and responding to the one before it at the same time each tiny door is a complete form in itself.”

Though Jonathan Morse got his start as a photographer and now realizes his images entirely on the computer, he still considers the final prints at least in part dependent on the act of drawing. “For me, photography was always a mark-making medium, rather than a way to depict the so-called real world. In decades of printmaking, now digital of course, my images have always employed drawing in various forms, even though I have never sat down to just draw per se,” he says. “But now, assisted by simple Photoshop methods, I can be a mark-maker in ways I could never have conceived in my traditional photo-printmaking days. My drawing inspiration sometimes come from drips and drops on the sidewalk, graffiti images, or close-ups of construction detritus. And sometimes from using a drawing tablet connected to the iMac.The mark, for me, is inherently primal. As I work, I feel the kinship of generations all the way back to cave painters.”

Jonathan Morse, Verdes 5 (2015), pigment print on Moab Juniper Baryta Rag, 22 by 34 inches

I could add that there are so many artists on the site who rely on drawing in one way or another—William Norton with his finely incised lines on Plexiglas, Anne Lindberg’s delicate traceries with string or graphite, and quite a few others—but if I keep going on Robert Hughes will surely rise up from the grave and slap a length of duct tape across my mouth. But that too might be a form of drawing.

Ann Landi

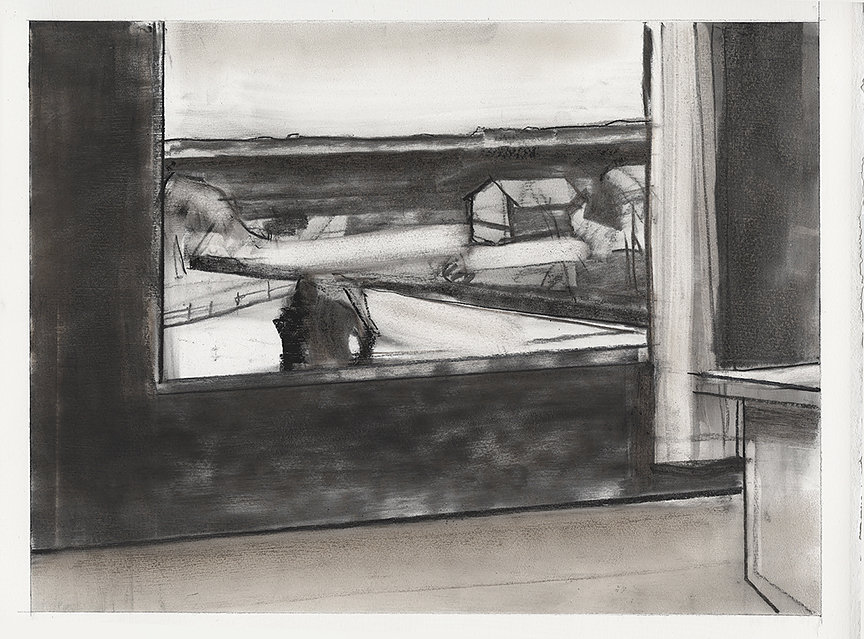

Top Image: Christopher Benson, Tiverton Window

Ann this piece is great!

Drawing =Painting.

Painting = Drawing.

I had the opportunity to visit the Paul Klee Museum– housed in a stunning

Renzo Piano building. The exhibition was entirely dedicated to the process, how Paul Klee prepared his paper, using gesso, plaster gauze ..how he transferred a drawing on to the watercolor painting etc.One of Klee’s famous statements is: “No day without a line”

Double Cheers, my new studio is almost finished.N

Whether I am working in graphite or oil, the approach is so very similar in my working with layers to build the imagery that they are almost synonymous. Rendering graphite in each layer to a state I want, then fixing that layer and starting again… akin to glazing with paint.

Lovely article, Ann, and I enjoyed it very much. Thank you for including my comments.

“I’ve always been more interested in Photoshop than Grasshopper, because Photoshop is a thing which allows you to intervene in the status of the image itself. It’s kind of a totally seamless collage. You can reinvent the world through the image rather than a digital model. That’s where it is an exciting space of a tool as an imaginative thing rather than a technical thing.” Architect Sam Jacob writing in Archetizer about his 2014 Yale studio experience.

Anyone who loves drawing will love the Kentler International Drawing Space in Red Hook, Brooklyn, NY. In operation for 26 years, and artist-founded and artist-directed, this ground floor space is dedicated to the expansion of the definition of drawing. I have served on the Artist Advisory Board since its inception and I am always amazed at the new ideas that come to our attention. We have an open, online application, with no fixed deadlines and no fees to apply or get your work seen. I will leave the Kentler website address below. Best regards to those who draw everywhere every day, Mariella Bisson

Great reading and very inspiring! Thank you, Ann.

Wonderful, Ann, mark making is one of my favorite things and drawings are always a part of my paintings.

Sharing with my students.

Thank you, Sheila

Wonderful article, Ann. so many interesting visual ideas. I learned a lot. Thank you.

Great piece Ann– thanks for posting!

Thanks, Ann, for this terrific piece on drawing that breaks down boundaries. What exciting artists!

Ann,

This is a great article. Vasari 21 is my go to reading every day.

Thank you.

Diane Di Bernardino Sanborn

Really enjoyed reading this wonderful article about my favorite subject! Thanks!