By the Book

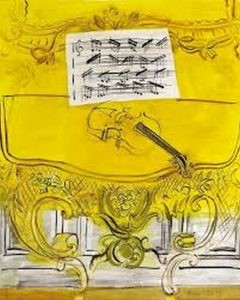

Artists Tell Us About Their Favorites The very first art books I remember reading (or perhaps just looking at with awe and wonder) were part of the series called “Metropolitan Seminars in Art,” written by the critic John Canaday. Each slender gray volume came with a slipcase of prints, and though the books have long vanished from my library, I can still recall vividly the enchantment of Degas’ Woman with Chrysanthemums, Matisse’s Lady in Blue, and Raoul Dufy’s Yellow Violin (formally, The Yellow Console with a Violin). I could not have been more than eleven or twelve when these volumes arrived in the mail, and so I doubt I read much of the text. Later, of course, when studying art history, scores of excellent books on art (many of them mentioned here) became required reading, but none sticks in memory quite like those first enchanted encounters.

The very first art books I remember reading (or perhaps just looking at with awe and wonder) were part of the series called “Metropolitan Seminars in Art,” written by the critic John Canaday. Each slender gray volume came with a slipcase of prints, and though the books have long vanished from my library, I can still recall vividly the enchantment of Degas’ Woman with Chrysanthemums, Matisse’s Lady in Blue, and Raoul Dufy’s Yellow Violin (formally, The Yellow Console with a Violin). I could not have been more than eleven or twelve when these volumes arrived in the mail, and so I doubt I read much of the text. Later, of course, when studying art history, scores of excellent books on art (many of them mentioned here) became required reading, but none sticks in memory quite like those first enchanted encounters.

Inspired by that memory late one Saturday night, I put the call out to Vasari21 members to find out what books about art and artists (or even books on other subjects) had inspired their creative practice. The answers are surprisingly varied; even more surprising, there is no overlap whatsoever in the selections given here. I found a couple of volumes I want to revisit—like Suzi Gablik’s Re-enchantment of Art—and quite a few I want to read for the first time.

Alison Berry

George Kubler, The Shape of Time.

Kubler (with whom I studied Pre-Columbian art in general and Mayan art and epigraphy in particular as an undergraduate) opened my eyes to a broader cultural perspective beyond the European tradition. His book presents a way to appreciate, value, and interpret the symbolic inflections of diverse cultures.

Joseph Campbell, The Mythic Image

Campbell’s work, which I discovered through reading Carl Jung, offered a global intellectual and symbolic voyage. His work had begun with Native American cultures and ranged globally, exploring and comparing the ideology of many religions (aka mythologies or world views) and their symbolic expression in literature and art.

Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time

The proverbial BIG questions still inspire me, and in the late 1980s, adrift from traditional religious moorings, buffeted by mixed messages from both scientific and religious worldviews, I discovered Hawking’s book. Its brief but scientifically sophisticated narrative offered a path forward in my quest to understand and symbolize my own time and culture.

Morgan Russell

The first book to pop into my head was The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien. The scope and depth of Tolkien’s world just about blew me away, I loved the journey, the adventure, the invention of places. But as I thought about the question of what deeply influenced as an artist, I felt like I had to go back to my formative years (I first read Tolkien as an adult). My favorite book as a child was Go, Dog, Go! by P.D. Eastman. I know it seems silly to list a children’s book as an influence, but bear with me. To this day I remember the illustrations on last few pages: dogs climbing a ladder through a fabulously big tree, and a party on top of the tree. I pored over those pages time and again.

In the local library soon after I left New York I stumbled upon Robert Rosenblum’s, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko. Important in that it helped me to legitimize an underlying draw I always had towards nature, this during a difficult transitional period in my work. Next I found What Painting Is, by James Elkins. This book got me thinking of paint as more of an entity unto itself.

Finally, a book that, like the previous two, I also read in the past nine or so years: Surprised by Joy, by C.S. Lewis. Near the end of this early autobiography, Lewis relates a memory of his older sister describing to him a snowfall on the hills near their childhood home. It’s a very visual explanation, involving potatoes covered with a blanket and dusted with flour. Her artistic description was far more important in his memory than a more factual explanation of the event and this completely resonated with me.

T.J. Mabrey

William Irwin Thompson, The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light

Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness

Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory

These authors speak of culture and consciousness in the light of myths which have helped me “see the light” and understand the reasons I do what I do in my creative life. Yates helped me identify the images I’ve created in historical terms, and which have become mnemonics for mapping and understanding my role in this journey called life.

Millicent Young

Fernand Windels, Lascaux

This was my mother’s book, now mine, with the glassine cover now yellowed and flaking. It was the book I pored over as a very small child, on the floor under my mother’s desk when she was correcting her anthropology students’ exams. It is the first memory I have of being mesmerized by art.

Suzi Gablik, The Re-enchantment of Art and Conversations Before the End of Time

Gablik was panned and vilified when “Re-enchantment” was published, but for me it was a turning point in restoring my purpose and faith in the endeavor of making art. I encountered “Re-enchantment” in graduate school. I didn’t agree with a lot of her examples, but the core messages resonated deeply. “Conversations” was written in the wake of the negative response to the other – some amazing interviews with artists, critics, gallerists, humanists….

The October Palace, poems by Jane Hirshfield

One of many collections by one of our most eloquent contemporary poets. Her poetry has figured prominently in my work and it was through this volume that I was first introduced to Jane’s work. Out of it our meaningful, treasured friendship as artists grew.

Elisabeth Condon

Flowers, Irving Penn

Almost erotic images of flowers in overblown, portrait scale. The flowers in various stages of decay are photographed against a white, light-filled surface. The book has a beautiful square shape. This was my mother’s book, and she asked me to paint a rose from it for her in oils. The detail work was fun because it was so lucidly photographed and so had greater potential for abstraction as I worked. This book lay dormant in my consciousness until a six-month stay in Shanghai in 2014, where the architecture was modeled after plant forms, and then it returned with stunning force to inspire the wallpaper and fabric paintings I am making now. (See https://vasari21.com/elisabeth-condon/)

Francois Cheng, Empty and Full

Philip Guston’s famed 1978 lecture mentions Song Dynasty painting. Galvanized to see examples of what happens “when even the artist leaves the room,” I began to research the great masters from the period. I was sufficiently shocked and impressed by Fan Kuan and others to fly to Taipei for three days to see a Song Dynasty exhibition at the Palace Museum (2006). Then I discovered this seminal text—a lucid, metaphysical disquisition on Chinese ink painting.

Agnes Martin, Writings

I bought this book years before I read it in earnest, but Martin’s essays remain a clear portrayal on the urgency of painting. Her stringent practice of Buddhist philosophy as a foundation and stark, urgent discussion of solitude remains inspiring enough that I take this book wherever I go as a touchstone and reminder.

Barbara Rachko

Camille Pissarro, Letters to His Son Lucien

This volume of weekly letters from the Impressionist master to a beloved son, who was just beginning his own artistic journey, was written over a two-decade period and conveys Pissarro’s wisdom about his craft, art, and life. I discovered this gem about 30 years ago when I was just starting to find my way as an artist, too. Pissarro’s words are beautiful, poignant, and deeply-felt. He has much to offer to artists because, sad to say, we still contend with the same problems he struggled with in his day—such as how to remain authentic and earn a living, how to deal with galleries and collectors, how to stay focused on the work, etc. I often enjoy rereading favorite passages simply because it makes me feel less alone as an artist.

Julian Hatton

David Hume, An Inquiry into Human Understanding

Why: still relevant. David Hume’s hypothesis that science is nothing but one of many systems that helps man survive and thrive undermines the Kantian obsession with certainty and ultimate truth. His attitude that one never knows ultimate causes, and doesn’t need to, allows us to focus more on what suits us best.

Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Denial of Human Nature

(See chapter 13, “The Arts.”) Essentially, some of the elite universities and elite museums, while under the influence of various intellectual fads such as post-modernism, refuse to acknowledge the role of human nature in influencing our aesthetic sensibility . As Hal Foster pointed out in his recent interview at the Kitchen, he might have thrown the baby out with the bath water. Beauty and pleasure are hard-wired human traits in evidence in all cultures dating back to at least 50,000 years ago, when the Australian aborigines used red ochre in rock painting.

Ernst Gombrich, Art and Illusion

Great example of using paintings and drawings to explain one’s hypothesis. And his hypotheses, argued around 1959, stretch into cognitive neuroscience and psychology before much was known about the physiology of the visual system.

Michael Thielen

Elie Faure, History of Art (five volumes)

I enjoyed the descriptions of how environment impacts the style of art of each place of origin. Japan, for example, is a volatile environment, as illustrated in the sharp jagged nature of the compositions of many of the landscapes. China’s immense size meant there was little change in art over time and it went virtually unstudied by the outside world. “The ever-changing reality which the occidental desires, the idealistic conquest which tempts him, and man’s attempt to rise toward harmony, intelligence,and morality seem to remain unsuspected by the Chinese,” Faure noted. “He has found,or a least thinks he has found his mode of social relationships. Why should he change?”

R.G. Collingwood, The Principles of Art

Collingwood, an English philosopher and archaeologist, studied the different purposes of art—“proper art,” art for entertainment’s sake, art as magic, etc. Collingwood believed that if an artist had an inkling of what he was hoping to achieve before he started on a piece, and ended up with a work that implied the original intent but wasn’t completely planned, then the artist was making good use of the creative process. True “art for art’s sake.” A piece of work that might embellish an idea or story would be considered “art for the sake of entertainment” and was another matter altogether. “Art for magic’s sake” might be something that lifted the consciousness or heightened the viewer’s spiritual experienc

Andrea Broyles

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

Audrey Flack, Art and Soul

Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art

These books are very inspiring to me mainly because they call out to the isolation of the artist’s life, confirm the feelings that all artists share in the struggle to continue creating, and basically say, “It’s okay. Keep going.”

Willy Richardson

Dave Hickey, Air Guitar

When I was in graduate school in the late 1990s in New York, the art world was set on cynicism and showing off intelligence. Hickey was pro-beauty and sincerity and anti-intellectual (although he is also pro rigor). He helped me stay the course of what I wanted to do, which was paint.

Dore, Ashton, The New York School

She was there, she took notes, she’s a great writer. Deep insight into the movement that allowed for so much freedom that we have in art today.

Lawrence Weschler, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing Seen: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert irwin

Irwin and Weschler are a great mix, and their conversation spawned a searching exploration of art and philosophy that is easily digestible, fun, and inspiring.

Susan Christie

Thomas Hoving, Making the Mummies Dance: Inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Photo credits: Degas’ Woman with Chrysanthemums,

Loved this article!

Enjoyed th article and now have several books added to my planned reading list.

what a great reading list! sooo many more have come to my mind – maybe we should have a “what I’m reading now” corner on the site

but I’m sure you have enough projects going on, Ann