Barbara Rachko

Barbara Rachko’s first career was about as far from the world of art as you can get. The daughter of working-class parents in suburban New Jersey, she earned her private pilot’s license at the age of 25 and then spent seven years in the Navy, becoming a lieutenant on active duty and working in what she describes as “a soul-crushing job as a computer analyst on the midnight shift in a Pentagon basement.” In the daytime, she took art classes and later reflected that her years in the service in many ways served her well: “The Navy taught me to be disciplined, goal-oriented and focused, to love challenges, and in everything I do, to pay attention to details.”

In 1989 she resigned her commission and turned to working full time in her preferred medium (and one she uses to this day), soft pastels on sandpaper. Her earliest efforts were portraits, a genre she soon found dissatisfying. When her future sister-in-law sent her a pair of two brightly painted wooden figures from Oaxaca, Rachko delved into the history of Mexican folk art—she had a long-standing interest in pre-Columbian civilizations—and she and her fiancé, Bryan C. Jack, began collecting the exotic figures who would soon populate her pastels.

On 9/11 she lost her brilliant husband, a high-ranking economist with the federal government, when the plane he was on board was hijacked at Dulles Airport and crashed into the Pentagon. (In a freakish twist, the plane flew directly into an office Rachko occupied as a member of the Navy Reserve.) What helped pull her from grief about a year later were the classes she took at the International Center for Photography in New York, learning to use her late husband’s large-format camera.

Photography is still a major part of her practice, and many of the same characters from her paintings occupy a separate, dreamy space all their own. “It’s a departure from the slowness of my work in the studio,” she says, “considering that in a good year I make five pastel paintings.”

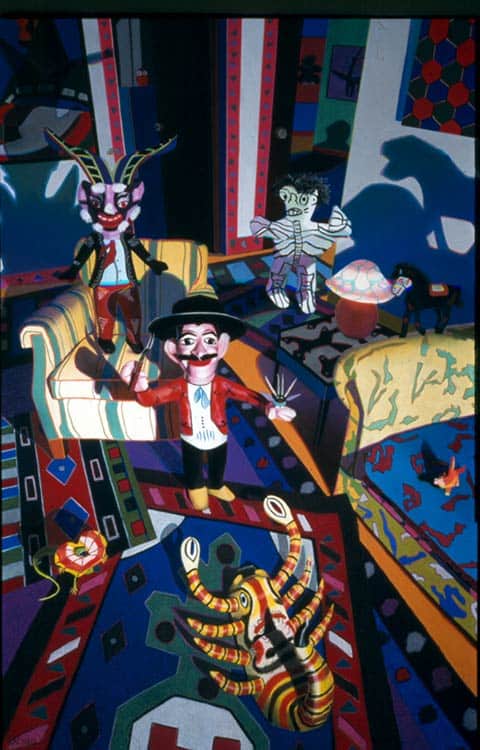

In her first series, begun in the mid-1990s and pursued for about 12 years, Rachko painted elaborate scenarios enacted by the mute characters from her collection. Aptly titled “Domestic Threats,” these offered the high drama of stage sets or film stills in which it’s really not quite clear what the action is about, but something strange is surely happening. The titles—He Urged Her To Abdicate or He Just Stood There Grinning—don’t do a whole lot to demystify the subjects but add another layer of mystery. They sound like lines plucked from a novel, or the titles of illustrations, but they look like the kind of nightmarish dramas a child might imagine going on among the denizens of his bedroom after nightfall.

As beguiling as these are on a storytelling level, they are also extremely smart and formally accomplished. Rachko knows how to set up a composition using pattern and shadow, light and dark, high-keyed color and subtle tones in such a way that the whole ensemble works together without becoming claustrophobic. Her antecedents are not in the folk traditions of the cultures she studies and embraces, but rather in the sophisticated strategies of Henri Matisse (who was a master at mixing patterns) and Edgar Degas (who exploited the power of oblique angles and cropped figures).

From her years as a portraitist, Rachko acquired some potent skills in her chosen medium. Though they never look labored, her paintings are made from multiple layers of pastels embedded in the toothy sandpaper ground. This gives the work a density and richness comparable to painting, and she is keeping alive a tradition that has all but died out—many artists find the medium too tricky and difficult for more than simple sketching.

In the last few years, in the series called “Black Paintings,” her works have acquired a different kind of power, not so much dependent on storytelling as on psychology and the pleasures of abstract shape. The works are more immediate, more “in your face.” In theatrical terms, it’s like moving from the elaborate stage machinery of a 19th-century melodrama to the stark existential angst of Samuel Beckett. These characters are more alienated, anguished, and paradoxically more human than their predecessors. They are not of our world, but they seem to make a silent plea for something like understanding. They are strange but lovable scamps, trapped in a world not entirely of their own making.

Ann Landi

Photo credit: Barbara Rachko in her Chelsea studio. One of her works will be on a billboard in New Orleans for Mardi Gras and for the entire month of February. She was formerly represented by H.P. Garcia in New York (who, like too many dealers, mysteriously disappeared) and is now looking for a new gallery in the city.

Thank you very much, my friend. This is beautifully written and looks terrific on the site!

Terrific article! Congratulations.

Une belle découverte de cette artiste très talentueuse. Un univers très riche, fascinant.

Bel article.