Is there still any distinction?

It might have been a test of how our perceptions of the unclothed body in art have changed over the past four decades: Seven years ago, at the Museum of Modern Art, a young man and a young woman stood facing each other in a doorway, immobile and wearing nothing. Visitors could choose to squeeze between them or to use another entrance into the exhibition.

The piece, called Imponderabilia, was a re-creation of a 1977 performance work by Marina Abramović (together with her then-partner, Ulay), and it was among the most talked-about aspects of her 40-year retrospective at MoMA. Most reviewers referred to the two people in the doorway as “naked,” but might they not also be thought of as nudes—living embodiments of a long line of sculptures of the human body stretching back to Greek kouroi, especially since the “performers” were trained dancers with well-toned bodies, who stood as stiff as, well, statues?

Naked or nude? Or something else altogether in our postmodern stew of mediums and messages?

Half a century ago, when Kenneth Clark published The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, he could make a clear distinction: “To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition,” he wrote. “The word ‘nude,’ on the other hand, carried in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone. The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled, defenseless body, but of a balanced, prosperous, and confident body: the body re-formed.”

The unclothed body is still a subject for artists, but how it is perceived is a more complicated question for us than it was for Clark. The people making academic nudes may still be sure of the distinction, but that is less true of the artists staking out new ground (and the curators and critics who support them).

Take the Abramović show. “Part of the power of her work with the body is that she breaks down the division that Clark makes, which has absolutely held true in art history,” says Chrissie Iles, the Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “When she’s making a work in which she’s naked, she is both naked and nude. Her body is very beautiful; it’s almost classical. At the same time, the context of her work and what she does with her body makes her very vulnerable. And in that sense, the nudity conforms more to Clark’s argument about nakedness.”

To RoseLee Goldberg, though, the terms are meaningless when it comes to performance art of a certain era. “The distinction between naked and nude was completely irrelevant,” says Goldberg, an art historian and the director of Performa, the New York–based performance-art biennial. “Imponderabilia was more about sexual politics, pure and simple.” Marina and Ulay, she says, “looked very much alike. They wanted to make it plain that there was this androgyny to the two of them. That’s what gets lost when you reproduce these things.” In the ’70s, when the work was first performed, it was “so much about the conversation of its time: Why should I have one set of values for a naked man and one set for a naked woman?”

When Minimalism and Conceptualism were dominant, Goldberg points out, “performance art was keeping the body alive.” Carolee Schneemann, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, Dennis Oppenheim, Eleanor Antin, Yoko Ono, and others were all making pieces “using the body to articulate political issues, dealing with class as much as relationships between men and women. Everything was showing the body as a vehicle for big storytelling.”

“The nude requires idealization, and that idealization has always had to do with traditions of depiction, which avant-garde work of the past 40 years has completely fractured,” says Schneemann. In her early performance works, Schneemann explains, she was “thinking about the freed energy of the exposed body in contradistinction to traditional restraints on how the body could be represented. In 1963, I used my naked body as part of a collage, and that was definitely when I was thinking about a way to disrupt the presentation of the female nude.”

Naked and Nude in Traditional Mediums

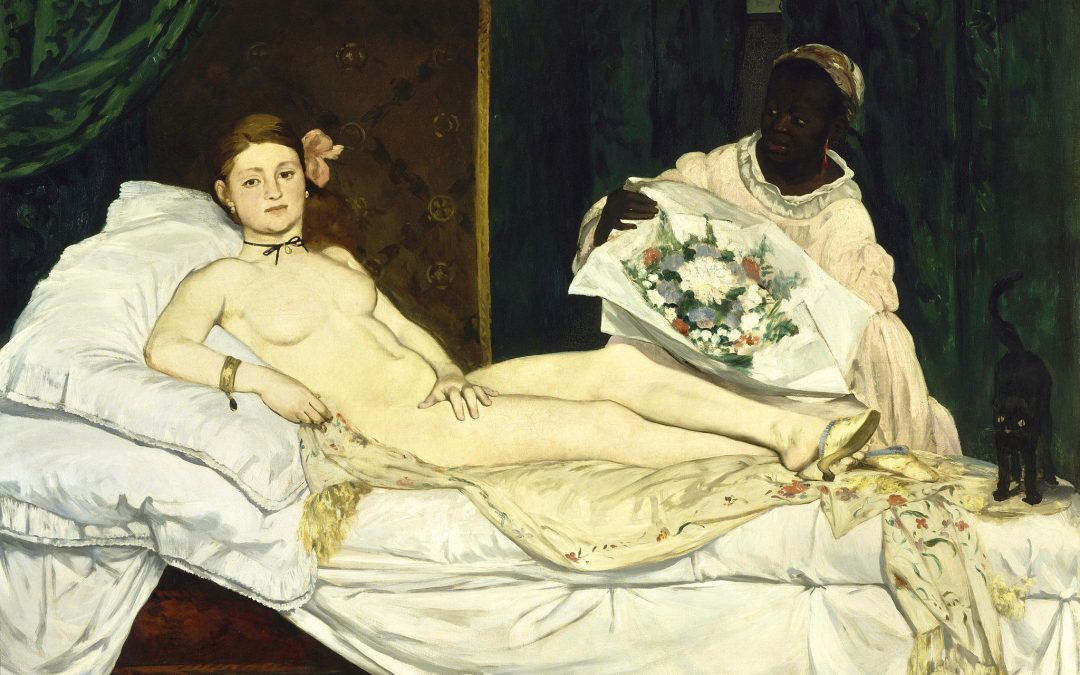

Yet when it comes to other mediums—painting, photography, sculpture—the categories “naked” and “nude” can still seem valid. For Elizabeth Armstrong, executive director of the Palm Springs Art Museum. the traditional nude walked out of the picture plane for good with Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), in 1912. “He was one of the artists who was hammering the last nails into the coffin of academic idealism,” a development that started with Manet’s Olympia. “I think it’s fair to say that one ambition of the nude is that it will seduce you. Nakedness is more raw. The expression ‘the naked truth’ comes to mind, because it captures the vulnerability of nakedness.”

Olympia, that celebrated shocker of the Paris Salon of 1865, kicked off a debate that continues today. “I would say she is naked,” says George Shackelford, senior deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, TX. “But she’s also a nude in the tradition of reclining nudes, and Manet is counting on your recognizing that fact. He’s counting on the above-average visitor understanding that he’s taking a Renaissance Venetian trope and recasting it in Grand Boulevard terms.”

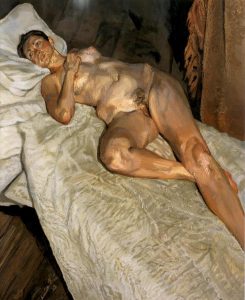

Closer to our own day, especially in painting, the conflation continues and the distinctions blur. Lucian Freud, for example, whose subject was often the unclothed human body, still inspires controversy. “His pictures have the memory of past paintings of the nude incorporated into them, so there’s a kind of primal memory of things he’s seen,” says Graham Nickson, an artist and the dean of the New York Studio School. Armstrong demurs: “Freud belongs in a discussion of the naked. There’s an exposure of the self, and that’s part of the difference between nude and naked within the context of art.”

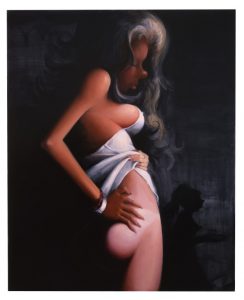

Yet while an artist like Eric Fischl can adamantly declare that his figures are naked because they express “vulnerability and anxiety,” Lisa Yuskavage, famous for her outlandishly proportioned female subjects, says the issue is not something she thinks about at all. “‘Naked’ and ‘nude’ sounds classist in a way to me,” she says. “Artfulness and high art versus everything else. The question of naked and nude doesn’t engross me because maybe I do both at different times.” Yuskavage says she is often asked, though, when she is going to paint a man. “The presumption is that I should be painting something for political reasons when what I’m doing is making the world I want to see,” she says.

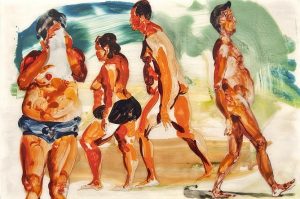

Nickson, who paints both unclothed and scantily clad figures for his series of “Bathers,” also sees himself as inhabiting a different camp entirely. “I’m trying to avoid those categories, the pigeonholing,” he says. “I often think of the bathers as not bathers. They are metaphors; they become ingredients in a different kind of theater, the theater of paint.”

Yuskavage is one of several artists who are known for painting inflated female bodies, often to the point of grotesquerie. Jenny Saville’s nude women are “mountains of flesh” with “neuroses bursting through,” according to London’s Guardian. She has also painted transvestites, using a model with a natural penis and silicone breasts. John Currin has painted near-pornographic images of women in garter belts and panties, but he is also capable of bringing a Boucher-like tenderness to images of his wife.

Iles sees these artists, particularly Currin and Yuskavage, as belonging to a different tradition entirely. “I think their references are much more to the Northern, Flemish approach to the nude,” she says, “a sort of realism and surrealism. There’s nothing ideal about either of them.”

Minding the Gap

An artist who playfully operates in the breach between naked and nude is Ellen Harvey, who in the past couple of years has completed two projects providing idiosyncratic overviews of nudity in Western art. The Nudist Museum (2010) documents every nude in the Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach. The more recent Nudist Museum Gift Shop (2012) offers up paintings of design objects featuring nudes, most of them junky tchochkes like ashtrays and vases.

“The art-historical nude created an aura of idealization that mass media have now perfected and moved to a point where you look at most porn stars and they don’t look naked; they look like they’re wearing a silicone outfit,” Harvey says. “Paradoxically most of these ‘sexy’ mass-media nudes end up seeming pretty unsexy.”

In almost all discussions of the nude, scholarly or otherwise, the subject of the unclothed black body, whether male or female, seldom enters into the conversation. “The black nude is still very tribal,” says Mickalene Thomas, who is examining old taboos in her photography and mixed-media paintings. “There’s still the need to associate the black body with something ethnic.”

Thomas has occasionally riffed on the work of the masters, particularly Courbet’s lush nudes and Manet’s Olympia. “When I use those particular, very iconic compositions, I choose them because I know that they will be shocking.” As for the question of naked versus nude, she says, “I like to say my work oscillates between both worlds. There’s a sensuality in both nakedness and nudity for me, a line of eroticism.”

With her photos of unabashedly beautiful young people, Mona Kuhn believes she is working quite consciously in the tradition of the nude. “I always feel that people are dressed in their own skin,” she says. In the introduction to one of her books, she quotes the philosopher Victor Tupitsyn: “To undress before a camera or an easel is to don the garments of representation, to take off one dress or costume, and put on another known as ‘the nude.’ . . . There is an assertion that the nude body is no less clothed than the clothed one, and that nudity is more impenetrable than a chastity belt.”

For Kuhn, “a nude then would be like an art-historical costume you can’t get away from. And if a nude is a costume, then naked would be a uniform. You would get naked like a prostitute gets naked for work.”

Curiously, few contemporary sculptors outside the academic tradition tackle the nude, male or female, even though the subject has had one of the longest runs in art history, from ancient times to Maillol and Giacometti. Among the sculptors who do consider the nude is Ron Mueck, an Australian, who makes hyperrealist sculptures of subjects that run the gamut from infancy to old age, and whose work is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. He plays with unexpected collisions of scale and subject: an infant may be blown up to gargantuan proportions but a spooning young couple or a robust middle-aged woman can be almost doll size.

Mueck’s work recalls Clark’s original evocation of nakedness as a “huddled, defenseless body.” Nothing could be more defenseless than Mueck’s over-life-size, deeply wrinkled, troubled-looking, and totally unclothed man, brooding in the corner of a gallery.

But naked or nude, political or sexual, remote or in-your-face, the body stripped bare will probably always command our attention, in real life and in art.

“The body is so fundamental that it will never disappear,” says Iles. “There’s been no period in art history when it hasn’t been front and center.”

Ann Landi

Top: It all starts here. Manet’s Olympia (1863)

Another great read and opportunity to see works I had not known of. Thanks Ann