The Lives of the Artists

Carol Rose Brown is a small, sharp, wren-like woman with piercing dark eyes and a surprisingly deep and resonant voice that retains traces of her native New York. She’s had more than her share of lumps in life—losing her beloved first husband in a terrible accident, enduring scoliosis and a car crash—but she has kept on working for more than 50 years, producing a diverse body of work that’s been shown all over the U.S–but not recently. Because, as she tells us in “Under the Radar” this week, she’s not quite ready to “shop around” the latest series, an ongoing project that has occupied her for about seven years.

Carol Rose Brown will probably never have a major museum retrospective or a profile in the mainstream art press (at least not in her lifetime, and not the way things are going with press coverage for artists), but she has been working as an artist since the age of 19. Because she is an artist and does not really have a choice in the matter. And, now in her 70s, she is producing the strongest work of her career.

The way that artists grow, change, and sometimes disappear for years (or forever) has long fascinated me. A few years ago, I wrote a review of El Anatsui’s retrospective at the Denver Art Museum for The Wall Street Journal. Anatsui is best known for the enormous dazzling wall “reliefs” he and his team make from recycled liquor-bottle caps and labels. To quote myself in the Journal, “these huge wall hangings drape in graceful folds and billows, suggesting tapestries, contemporary grid-based abstraction and African textiles….”

El Anatsui, Dusasa 1 (2007), found aluminum and copper wire. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

But it was a lifetime before Anatsui arrived at his signature formula, and as the retrospective in Denver demonstrated, much of his work from the 1970s through ‘90s, though politically pointed and acceptably cutting edge, in no way presaged the drop-dead gorgeousness and ingenuity of his recent output.

Without question, Anatsui, like Brown, is a late bloomer, and art history is rife with the stories of artists who did not come into their own until they were well beyond the launch phase, or who stalled and stuttered before finally taking off. Jean Dubuffet famously made many attempts to establish himself as an artist (supporting himself, meantime, by running the family wine business). It wasn’t until he was in his forties and began to make his “thick impastos”—paint mixed with materials like glass, gravel, cement, tar, and even bird droppings— that he made his name and determined a direction he could pursue for the rest of his life.

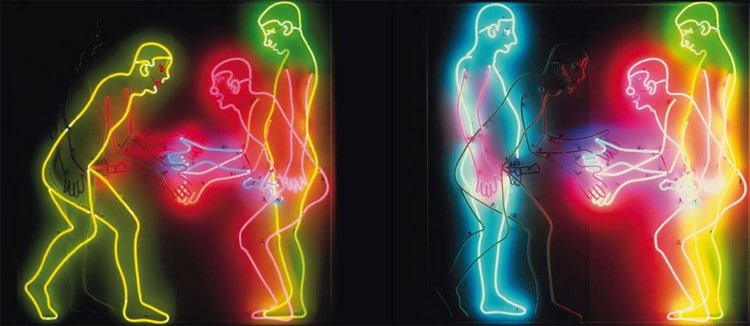

And then there are periods when an artist can’t work for one reason or another or seriously contemplates getting out of “the business” for good. After his retrospective at the Whitney in the early 1970s, prickly renegade Bruce Nauman couldn’t think about making art for several months. Later, when his career was in a more serious tailspin, he subsisted on a small stipend from Leo Castelli and at one point considered giving up art to turn a hobby of making handmade knives into a profit-making endeavor.

But of course there probably isn’t an artist alive who hasn’t had seriously fallow periods or had to make a living from something other than art. And there are no doubt numerous artists who have simply decided “this is too damn hard” and given up completely. (I might argue that if you throw in the towel, you’re probably not an artist at all.)

One of the great pleasures of launching Vasari21 is the number of incredible artists who have signed on—people who will probably not have careers like El Anatsui or Jean Dubuffet or Bruce Nauman. But the sheer volume of talent has made me aware of how many go unsung (hence the “Under the Radar” department of this site) and how different their progress through life has been. The career of an artist is probably one of the most difficult on the planet, but the rewards for most are not in the big glitzy museum retrospective, but the day-to-day progress in the studio—even during those times that might mean simply staring at the wall.

Photo credits: Carol Rose Brown, No Dominion (2016), archival digital photo

Yes, how very true about the day to day satisfaction ! Such a valuable reminder and such an important advocacy. Good to realize that there are many, working for the sublime

pleasure of producing something that extends beyond the usual, ordinary occupations.

Incisive and heartfelt thoughts. Thanks.

stunning piece, hits the mark of profound in a scattered sense

Love this…you are right, so many unsung artists.

Ann,

I relate to your words here so much. After painting since I was a small child I finally found my real voice as an artist 3 years ago at the age of 58. I always had to work some kind of job and I think having less time to work on my art hurt me and if I could go back and do a do over I would have done what I am doing now, working less, taking a hit in the money department and painting more, it has been life changing and it has done me nothing, but good. Advice for the young artist. I also agree, if you can live without doing art you are probably not a real artist. Thank you for your wonderful site. xoxo

Thank you for writing about artists who may not be young, trendy, or properly connected! I exhibited with Carol Brown years ago & have wondered about her continued work.

Belles découvertes de créations et d’artistes. Toujours un plaisir de. lire des nouveautés su Vasari21