Protests at the Whitney raise questions about race, politics, and bad painting

In case you missed it, the big art-world kerfuffle of the week, possibly of the season, happened following the launch of the 2017 Whitney Biennial last week when several artists took umbrage at Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket. The work is based on photos from 1955 showing the mutilated body of Emmett Till, the teenager who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi for allegedly approaching the wife of one of his assailants in a manner she considered offensive. The boy was beaten so brutally that his uncle could identify him only by an initialed ring. His body was sent home to Chicago, where his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to hold an open-coffin funeral. Mobley dealt with her loss, as two writers from The New Republic pointed out, “by controlling the postmortem narrative and the image of her son in death.”

“I know that his life can’t be returned but I hope that his death will certainly start a movement in these United States,” she said at the time. And indeed those black-and-white photos, among other documentation of egregious discrimination against African-Americans, helped lend momentum to the nascent crusade for civil rights in this country. (In a heart-breaking footnote earlier this year, Carolyn Bryant, the woman who accused the boy of flirting with her, confessed to fabricating the story and providing false testimony during the trial of Till’s murderers, who were acquitted.)

In this latest chapter of the Emmett Till story, an emerging 24-year-old black artist named Parker Bright objected to Schutz’s “appropriation” of Till’s image, which had surfaced on various social media sites. On the day the biennial opened to the public, Bright walked into the museum’s fifth-floor galleries wearing a shirt that read, “Black Death Spectacle,” and stood in front of Schutz’s painting, blocking it from view for several hours.

The following day the artist Pastiche Lumumba hung a banner from the balcony of the High Line, the urban walkway adjacent to the Whitney, that read: “The white woman whose lies got Emmett Till lynched is still alive in 2017. Feel old yet?” And somewhere in the midst of the gathering storm, Hannah Black, a Berlin-based writer and artist, published an open letter online, which has since been deleted, calling for the Whitney “to remove Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket and with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.” (I won’t even get into the lunacy of a fake letter from Dana Shutz asking that the painting be removed from view….because more fake news gets us into the realm of Trumpian surrealism.)

The museum’s curators, Chris Lew and Mia Locks, responded. The artist herself responded. In a letter to The Guardian (a British newspaper!), she stated, somewhat missing the point: “I don’t know what it is like to be black in America, but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension.”

But lost in all the coverage of the fracas, both online and in print, was any discussion of the painting itself. Schutz’s rendering of Emmett Till’s corpse shows the body from the waist up, the smashed head resting on a pillow, its features even more battered beyond recognition than in the photos carried by the media in 1955. But wait a minute! Is that indeed a face, and if so where are the eyes, the mouth, the nose? It looks to me (and, granted, I’m only judging from images on the screen) more like a badly smashed coconut or a carelessly trampled chocolate truffle. You’d have to know the original photo to realize the source, and this rendering of Till’s face is thus leached of any real power to shock. It’s simply inept painting, a self-indulgent stew of swirling brushstrokes. Even Picasso or Francis Bacon in their most exaggerated moments left us with some semblance of human features. Even the photo of Emmett Till tells us this was once a boy’s face, or we would not respond with such revulsion and sorrow.

In fact, the whole composition is strange: a scrim of what looks to be either seashells or flowers at the top of the canvas, the body reduced to stark geometries with a jaunty red rosette at the waist. It’s hard to know what this painting is trying to say (but then, admittedly, I’ve never been a big fan of Schutz’s cartoony expressionism). We had to wait for Schutz’s post-opening statement to tell us that she was approaching the tinderbox subject as a mother empathizing with horrific loss.

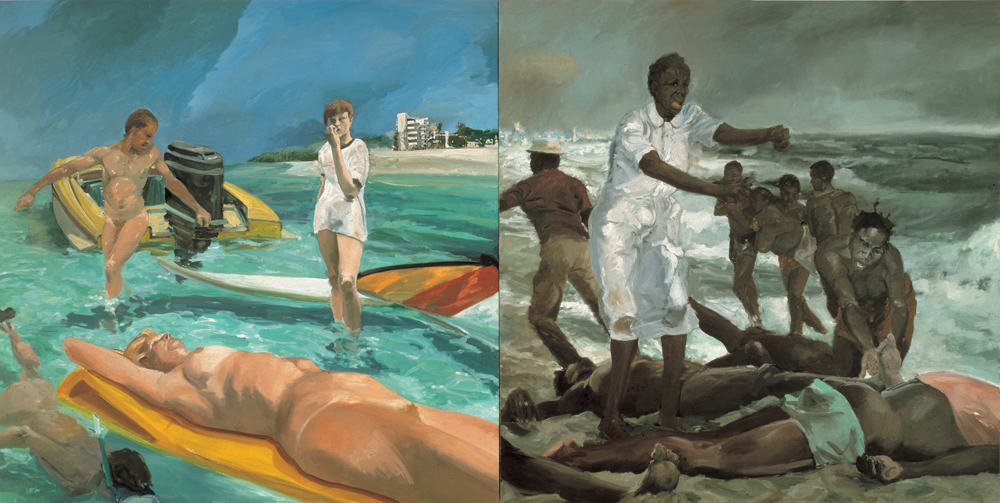

Yet the larger argument of the protests launched against Open Casket seems to be that a white woman—or perhaps even any white person—dare not approach black subject matter. If that’s the case, why was there no big hue and cry over Eric Fischl’s huge tableau, now on another floor of the Whitney as part of the show “Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s”? Half of that diptych (at the top of this post), called A Visit To/A Visit From/The Island, depicts dark-skinned Haitian refugees on a stormy beach, “a nightmarish vision, likely derived from photographs…, where people struggle, lament, and lie drowned,” to quote Peter Schjeldahl’s review.

So is it okay for a white male painter to tackle tragedies with racial implications (the Caucasians in the other half of the work are blithely oblivious to Third World suffering), also based on photos, but not all right for a white woman to do the same? Or should only people of color have the right to address the still shameful problems of racial inequity?

I wonder what the reaction would be if a white woman had produced one of Kara Walker’s saucy pickaninnies or banjo-strumming field hands. Or a coal-black semi-nude figure in the manner of Kerry James Marshall. I believe the response from people of color would be, “Hands off our stereotypes and our subject matter! That’s our legacy to dissect, but not yours.”

Race is a complicated issue, and will remain so for a long long time, but ultimately the power of any image lies in its ability to provoke, seduce, or unsettle. For me, Schutz’s painting does none of these. Only the protests against Open Casket lend it any real clout.

Top: Eric Fischl, A Visit To/A Visit From/The Island (1983)

Thanks for this letter and the images, Ann. I haven’t read any other reviews yet of the Whitney Biennial, nor have I seen it, being here in Santa Fe. My initial reaction to the painting in question, was ….”I don’t feel anything” ….Your questions re the uproar over who can paint what….are good ones, and maybe if I were to see the painting in person, it would be powerful. But I do thank you for bringing up the point…what about the painting itself…as a work of art?

Thank You Ann.

Superb writing. Although I do like Dana Schutzs work I admit that I did not get that horrible feel in the pit of my stomach that the photo provoked. Thank you for addressing some very important issues.

I am with you Ann. I am not a fan of Dana Schultz’s work (one of my least favorite artists), but I would not ever censor any artist. As a woman I may not be black, but being a female I feel I can relate to being put down, I have a right to that as a female who has been abused. It is true that we do not all have the same experiences, but that does not mean we can not make paintings about whatever and whom ever we want. Art is about freedom.

Thank you for raising the question of the value or success (& I mean emotional or otherwise substantive value) of the work apart from the seriousness of the stated subject matter. A lot of current art purports to address social & political issues. But, notwithstanding the ponderous explanatory texts accompanying much of it, I find it too often fails to convey any meaning or feeling, or to provide insight.

Of course, I agree that all subject matter is fair game for all of us. But if you’re going to deal with critical & sensitive issues, have something to say. Using hot-button issues to affect seriousness or relevance is BS.

If Dana wants to own up to it she should do 60 paintings about race inequality

Thanks for this Ann; a wonderful read about a curiously, really bad painting. I’m amazed it got into the show. That said, Schutz is, and should be free as an artist, regardless of her ethnic origins. to invite the public to her own lynching.

Well, on reading this for the first time now, and after many discussions in my classes and with friends, I find as a white, female artist, I still must respond with another perspective, though truly not as a reproach.

African-Americans are not simply ‘black’ people in our country and can not be compared with other racial or marginalized peoples, such as the Haitian refugees you point out. The history of slavery and the continued non-acceptance or non-acknowledged tremendous impact on generations of people in our society is still staggering. Perhaps a more interesting question would be: would that painting have been in the Biennial if it had been painted by an African-American? So few of these artists and their issues, have ever been given exposure. And now, a painting of an absolutely horrific murder that depicts a daily threat that many of our African-American citizens have lived with for generations, should be discussed by brush strokes and appropriateness leaves much open for consideration. While these views may be from our own, personal perspective, we sometimes forget our shoes often tread a different path and we might try on another’s pair to see their journey with a bit more understanding. That said, I do think artists should/need to paint what they need to, however, it should not be the end of the conversation. There are many marginalized people in our country and they all carry a different narrative. I am trying to listen more openly.

Ann,

Your good coverage of last year’s fuss at the Whitney Museum was spot-on.

Many thanks for pointing out the absurdities of that situation.

An artist’s right to self-expression, whether repugnant to some or not, represents freedom of speech.

Art that is censored by anyone for any reason denies that art and its creator a voice.

Let us keep freedom of expression front and center and not censor what work an artist may create or

a gallery or museum may exhibit. That can lead to self-censoring, a frightening consequence.

Especially now.