T.J. Mabrey

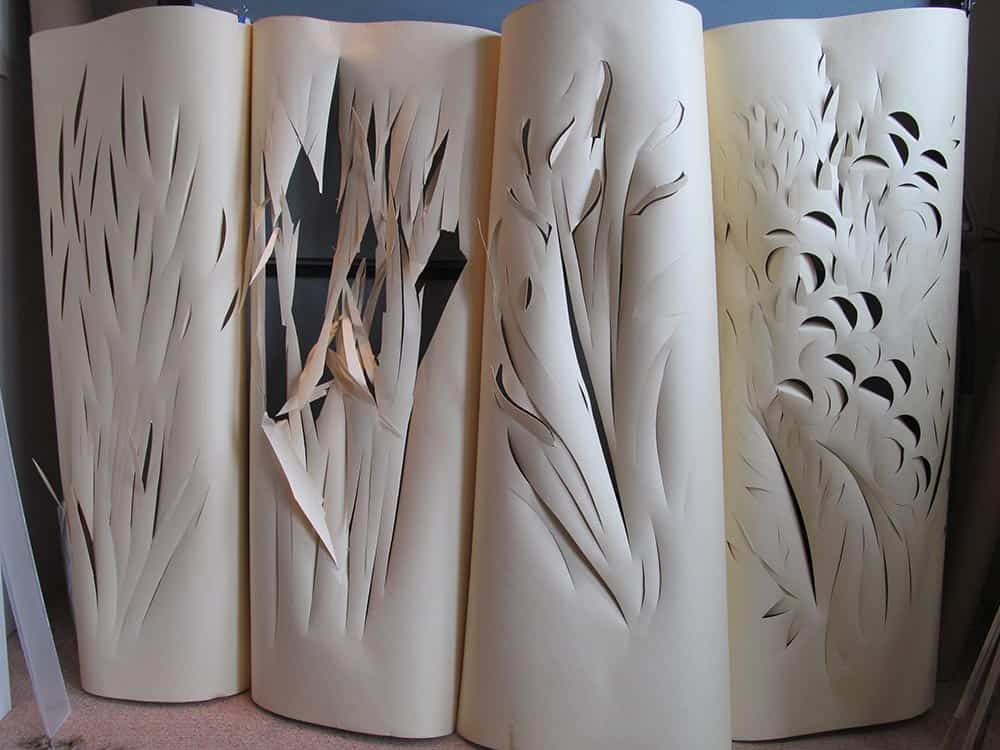

T.J. Mabrey’s journeys have taken her from Oklahoma to Dallas to Panama to the marble quarries of Pietrasanta to Singapore and Cairo and most recently to Taos, NM, where she has a buoyant installation—made almost entirely of paper— that fills the gallery of the Taos Center for the Arts. Pale ochre sheets of Manila paper, folded into accordion-like pleats and threaded through with snatches of poetry by John Campion, line several of the walls. A big bouquet of translucent blossoms floats from the ceiling. And columns of cut paper, which appear to trap light like low-burning lanterns, march across one of the windows.

I ask Mabrey if it doesn’t bother her to have put months and months of work into such an ephemeral medium. “Well, it’s archival paper, so it will last a long time,” she answers in a slow infectious Texas drawl. “But it could also be translated into bronze, copper, aluminum….”

Though some of her earliest experiences were with printmaking at Oklahoma State University—classes that taught her how to be “methodical and extraordinarily focused”—Mabrey has worked steadily in marble, drawing on influences from a wide variety of sources. Married to Stephen Mabrey at the age of 23, she landed in Panama two years later, where her husband worked for the government, flying a helicopter to draw up maps of remote parts of the isthmus. She was not able to set up a studio there, but had a chance to study local textiles and pre-Columbian sculpture.

Next came Dallas for 15 years and four years of intensive study with Octavio Medellin, a Mexican artist who offered private classes in a variety of mediums. “I did ceramics, I did wood carving,” she recalls. “I was there almost four days a week, and I learned more in those four years than I could at any university.” She showed in invitational exhibitions, competitions, and private galleries, and by 1979 decided that she wanted to carve marble at the source—at Pietrasanta, in northern Tuscany, where Michelangelo discovered the beauty of the local stone some five centuries ago.

Mabrey sent a letter to Tramell Crow, a legendary Texas real-estate developer, asking him for $3000 to set up a studio in Italy. Much to her surprise, he gave her the funds. “I found a little pensione in the town of Pietrasanta. I could walk to a shared studio space from there,” she says. “You could learn from the artisans in those days—if you wanted to know how to carve roses or feathers or architectural adornments. They’d say, ‘Come on in. Have glass of wine. Let me show you how to do that.’”

For many years, even after Stephen’s work with the Foreign Service took them to Singapore and Cairo, T.J. spent a few months each year carving in Italy. But she was privileged to enjoy art adventures in other exotic spots. In Singapore, she saw work by contemporary Chinese watercolor artists, who took her under their wing. In tandem with a performance artist there, Tang Da Wu, she made 10-foot-tall joss sticks, embellished with mythological characters and symbols, which were carried to a koi farm and then set ablaze.

“In Italy, you could learn from the artisans in those days. If you wanted to know how to carve, they’d say, ‘Come on in. Have a glass of wine. Let me show you how to do that.'”

Later, during the early 1990s in Egypt, she had a studio near the pyramids, by a canal. “I saw water buffalo, boats, local women carrying big baskets on their heads.” She was close to a large stone yard and could find remnants of old temples, chunks of granite and porphyry, to use as raw materials for her sculpture. (One of the works made in Cairo—a barge-like piece carved from alabaster and pink and black marble—was acquired by the U.S. ambassador.) She also became friends with Anna Bogighian, an engagingly eccentric and largely nomadic artist who was included in the prestigious German art fair documenta. “She would cart me off to the coffee houses at night, where all the artists would gather,” Mabrey remembers. “It was very unusual for a woman to be involved in those circles, but she was always accepted.”

In Cairo, she also found a new medium to explore—papyrus. “You could go to the factory and get stacks of this stuff. It’s fantastic to work with. You can wet it and mold it, you can grind it up. You can write on it.”

In time, the Mabreys gravitated back to the U.S. and central Texas, in part because her parents were growing older. Stephen retired to study massage therapy, and T.J. became active in Democratic politics, so adept at the game that the feminist political action committee Emily’s List wanted to coach her in running for office. But by then the peculiar dogmas and the harsh climate of Texas had taken a toll, and the couple decided to move to Taos in 2011. In collaborating with Campion for the Taos Center for the Arts, Mabrey is continuing with themes that have preoccupied both her and the poet for many years: sustainability, ecological consciousness, and what she calls the “life-giving elements of the world.”

When asked if all her travels, working in so many different cultures, have had an impact on her art, she says: “Everything you see is a conglomerate of knowledge learned from so many different teachers. How to put things together—and how to remember how you put them together.”

Ann Landi

T.J. Mabrey has exhibited her work in diverse mediums in Texas, Washington DC, New York, Holland, Singapore, Italy, Egypt, and New Mexico. Her show “Migration, Metamorphosis, Symbiosis, Emergence” will be on view at the Encore Gallery of the Taos Center for the Arts through July 17, 2016. Her sculptures are featured in “SEED: Disperse” at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, CO, through July 4, and she will have three marble pieces in the forthcoming Third Annual Artspace 111 regional juried exhibition in Fort Worth, TX.

T.J. Mabrey has exhibited her work in diverse mediums in Texas, Washington DC, New York, Holland, Singapore, Italy, Egypt, and New Mexico. Her show “Migration, Metamorphosis, Symbiosis, Emergence” will be on view at the Encore Gallery of the Taos Center for the Arts through July 17, 2016. Her sculptures are featured in “SEED: Disperse” at the Dairy Arts Center in Boulder, CO, through July 4, and she will have three marble pieces in the forthcoming Third Annual Artspace 111 regional juried exhibition in Fort Worth, TX.

Photos: Top, from an undated performance piece in Singapore, Photos of T.J. Mabrey and her installation at the Taos Center for the Arts (June 2016), Kathleen Brennan

Ann,

WOW, just WOW. What a life, wonderful art and a beautiful show.

Fascinating to learn about TJ’s life and work!

So glad to see this article about TJ, she has had a remarkable life.