A few weeks ago my neighbor and Vasari21 member TJ Mabrey asked me why I didn’t suggest some books for the warm-weather season, when supposedly we all head for the country or the beach armed with a Kindle or a stack of paperbacks. Since I am always reading biographies of artists, memoirs by artists, and occasionally deep thoughtful books about art, I offer up here three to get you started, in no particular order.

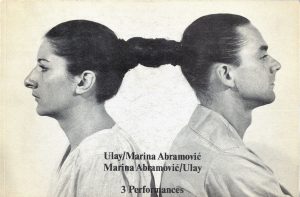

Marina Abramović: Walk Through Walls (Crown Archetype Books, 2016). In the course of her long and well-documented career, Marina Abramović has slammed her naked body into concrete walls, scrubbed bloody cow bones, lived for two weeks in the windows of a Chelsea gallery, walked the Great Wall of China, nearly suffocated inside a framework of fire, and most memorably sat immobile day after day in a kind of face-off with strangers at the Museum of Modern art for the ten weeks’ duration of her 2010 retrospective.

It’s possible her childhood in Yugoslavia, the daughter of distinguished war heroes who were indifferent or cruel to the young Marina, helped shape a predilection for self-abuse. “I was punished frequently, for the slightest infraction, and the punishments were almost always physical—hitting and slapping,” she writes. Her mother and aunt beat her “till she was black and blue.” For her 14th birthday, her father gave her a pistol, and she brought a schoolmate home to play a game of Russian roulette (the bullet landed in the spine of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot).

But don’t expect Abramović to do a lot of heavy soul searching as to why she does the things she does. Instead, this harrowing and occasionally funny account takes us on the artist’s journey to art-world mega-celebrity. You may get annoyed at the often breathless and unpolished prose (“time stopped as we stared into each other’s eyes”). You will need to withstand a fair amount of woo-woo talk about tarot cards and clairvoyants and kundalini life forces and gurus and monks. And you will undoubtedly be nauseated by the descriptions of some her of performance work. But for all that, Abramović has a flair for dramatic storytelling and has lived one hell of a life.

Sally Mann: Hold Still (Little, Brown and Company, 2015). Some may remember the huge controversy that attended the publication of Sally Mann’s photographs of her three children, in a collection called “Immediate Family,” in the early 1990s. In the photos themselves, of the kids naked and often striking make-believe adult poses, and in the profile presented in The New York Times Magazine, Mann came off as imperious and a bad mother, willing to sacrifice her children to her art. The reaction was swift and outraged: reams of letters to the editors, harsh assessments by critics, and assaults on the family, including at least one person who harassed them for years.

Two decades later, the photographer coolly assesses the reaction and her own response, but this book is far more than a photographer’s memoir of her subjects. Mann is a stylish and commanding writer who has sifted through a trove of family papers and old photos to excavate a Southern past more gothic than any imagined by Carson McCullers or William Faulkner. Generously illustrated, this is a story of troubled but gifted parents, memorable ancestors, long-suffering family retainers, clandestine affairs, and murder and suicide.

Most bracing of all is the way the artist writes about her vocation and what drives her. “Art is seldom the result of true genius,” she writes, “rather it is the product of hard work and skills learned and tenaciously practiced by regular people. In my case, I practice my skills despite repeated failures and self-doubt so profound it can masquerade outwardly as conceit. It’s not heroic in any way….I make bad picture after bad picture week after week until the relief comes: the good new picture that offers benediction.”

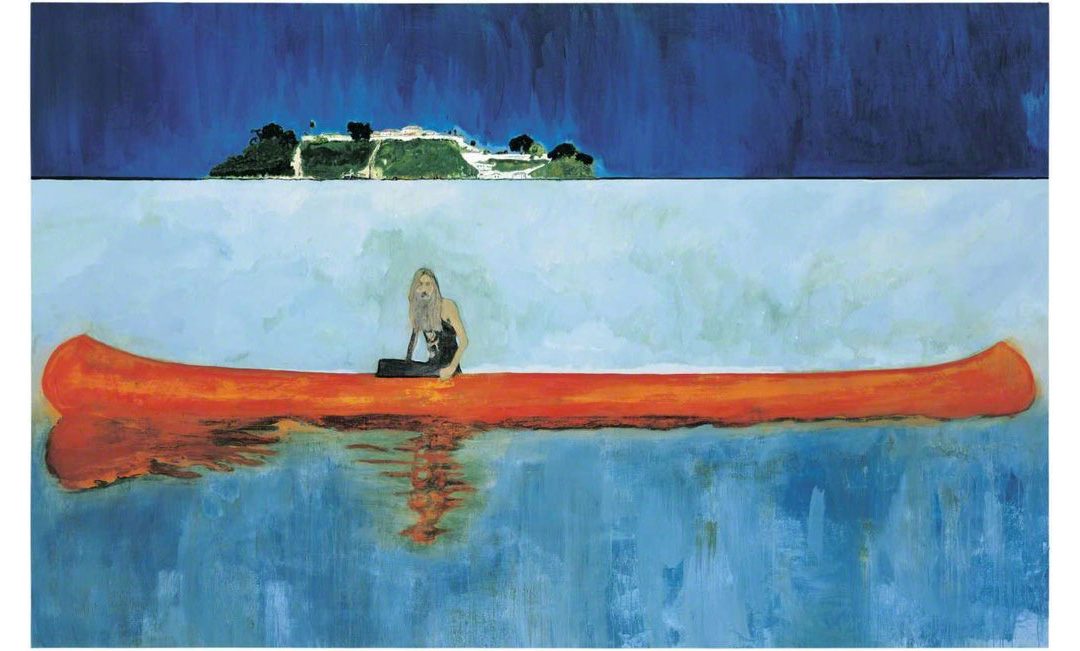

Derek Walcott and Peter Doig: Morning Paramin (Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 2016):

On the surface, the late Nobel laureate Derek Walcott and artist Peter Doig might have seemed unlikely collaborators for a volume of pictures and verse. Nearly 30 years and 200 miles separated the two friends, who both made their home in the Caribbean—Mr. Walcott in St. Lucia, Mr. Doig in Trinidad—but hailed from very different backgrounds.

Yet their respective endeavors offer much in common. Both are accessible artists who paradoxically maintain an air of aloof but beguiling mystery. Walcott relied on old-fashioned pleasures of poetry: internal and slant rhymes, couplets, even storytelling. Doig works with the painter’s time-honored arsenal of pigment, canvas, and brushes and fits into a figurative tradition that relates him to artists like Edvard Munch and Henri Rousseau.

So in Morning, Paramin, the poet’s last book before his death in March of this year, Doig and Walcott attained a kind of double-barreled magic as the poet responded to 21 of the artist’s paintings. It’s a journey that takes the reader from snowy northern landscapes to steamy jungles and tropical beaches. And at the most elemental level, Walcott sometimes invents a narrative to go with painter’s canvases.

Like Doig’s paintings, the poet’s observations are often tinged with acid; the gorgeous colors speak of threat and violence, and ecological disaster. Walcott warns, “We have done things to nature in our time./The victim may be missing but not the crime.”

This is a book that can be savored all in one gulp—on a lazy summer afternoon, in the hammock or under a shady tree. Paintings and poems summon up landscapes and cultures, from the exotic to the familiar, along with a profound friendship between like-minded spirits. Like all great reading experiences, this one leaves you both subtly changed and repeatedly delighted. And it will perhaps spark a real desire to see larger examples of Doig’s work whenever and wherever possible.

Ann Landi

Top: Peter Doig, 100 Years Ago (Carrera), 2001

Photo credits: Abramovic and Ulay by Marina Abramovic and the CODA Museum; Sally Mann photo courtesy of Lucy Burrluck