If you catch a set decorator’s eye, it just might happen

As readers know, I have developed a peculiar fascination with the art featured in shows on the big and small screens—who chooses this work? where do they find the art? what are the guiding factors behind the selections? And so I’ve spent a couple of weeks researching the topic and wondering if there’s anything here for a Vasari21 audience.

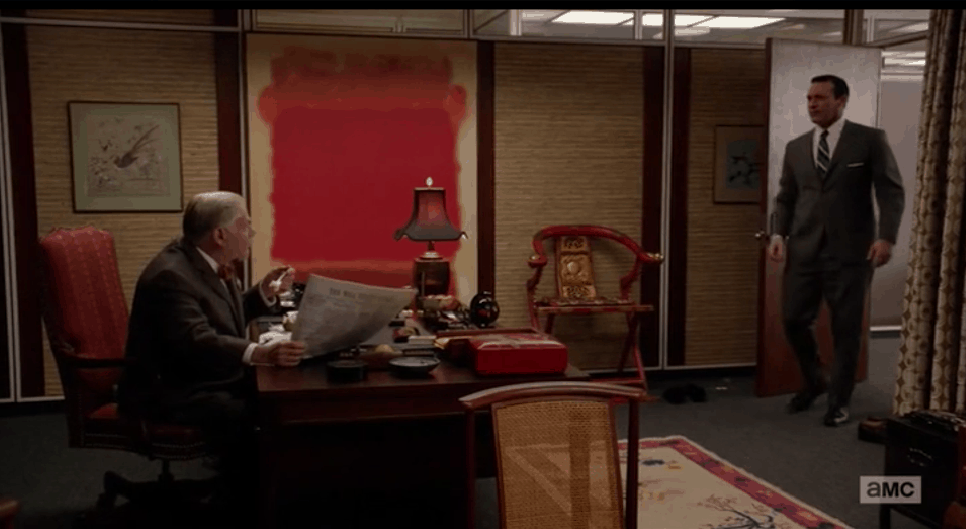

Even if you’re not giving art on-screen your full attention (and you should, after all, be paying more heed to plot and characters), art objects and set design go a long way toward establishing an overall look and mood. The offices of Sterling, Cooper, the ad agency at the center of the long-running series “Mad Men,” would lack a certain tone without the rather cheesy examples of 1960s Op and Pop, which define the principals as both hip and clueless. Similarly “Halt and Catch Fire,” about the early days of the personal computing revolution, had to capture a particular ‘80s ambience in the homes and offices of the characters. (For that one, set decorator Lance Totten combed through back issues of Texas Homes and D Magazine and also discovered in the old Sears catalogues a mother lode of visual information on what middle-class homes from the period looked like.)

The professional in charge of putting it all together is known as a set decorator, and typically she works closely with the director, art designer, and production designer. A seasoned set decorator like K.C. Fox, who has been in the business for more than three decades, will work with a substantial staff. As a department head on the TV series “Criminal Minds,” she has two assistants and a crew of up to 20 people who are dressing the sets under her supervision. Not a huge number when you realize how much has to be taken into consideration—not just art, but carpeting, furniture, draperies, and all kinds of minutiae. For example: “If you open drawers on the show, what sort of things will they have inside them?” she asks.

“Optics” can include dimensions that go way beyond whether a piece of art will look good hanging over the sofa. “I have to ask what works well with an actress’s skin tone,” says Beth Kushnick, who has been the set decorator for “The Good Wife” and, more recently, its spin-off “The Good Fight.” If an actor is standing in front of an artwork, she says, “it can’t be so distracting it saps attention from what he’s saying or doing.” And, of course, it can’t appear to be “growing out of the character’s head.”

It’s the set decorator’s job, says Fox, “to create a background that supports the story the director wants to tell.” To get a sense of how a set should look, and what art should be included, Totten claims, “I read the written material, have a series of meetings with producers and directors, and spend as much ‘creative’ time as possible getting info from the production designer on what all the sets should look like.” A single hue might even determine the overall look of a set: As Kushnick explained in one interview, “When you look at ‘The Good Wife’ you can see that it was a very warm palette of color with a lot of red. This was due to the fact that we went with the concept that law was a blood sport. “

And where does the art come from? Sources are many and various. Certain shows may have an inventory of work to choose from. Set decorators often have artists they have worked with for years who can be called on to provide a certain “look.” Kushnick, who studied art at Syracuse University three decades ago, uses pieces from artists like Li Trincere, Noelle Giddings, and Barry Shapiro. “I’ve taken the most modern of pieces and used it in a more traditional setting to say something about a character—that this person is well traveled and sophisticated and has the means to buy impressive art.”

Often finding the right art is pure serendipity. Fox, who has a certain budget for “Criminal Minds,” sometimes stumbles across works in thrift stores that might be appropriate down the road. When he was the set decorator for “Bloodlines,” a dark family drama set in the Florida Keys, William Cimino met art dealer Nance Frank from Gallery on Greene in Key West at a party and enlisted her help in finding the right art for the beachfront hotel that is a principal site for the action.

There are also warehouses that specialize in huge inventories, like Hollywood Studio Galleries in L.A., which is described online as a “a prop house that rents cleared artwork to the entertainment industry.” Or the Artspace Warehouse, also in L.A., which offers a smorgasbord of services, including art consulting and rentals, artworks for movies and television, and a 5,000-square-foot “affordable art gallery.” Owner and director Claudia Deutsch says, “Set decorators can find a whole range of artworks that aren’t on other sets. You don’t want to see an artwork on one show and then it turns up somewhere else. We have an online gallery they can scroll through and order by size, color, and style.” Among other projects, Deutsch has worked with Amy Feldman, Emmy-award-winning set decorator for “Two Broke Girls.”

Vasari21 member Susan Washington says that Artspace has placed one of her paintings in a movie but the gallery won’t say which till May 1. Deutsch, who seems to act as both dealer and consultant, has also sold Washington’s work at the Affordable Art Fair. (Artists interested in pursuing a connection with the Artspace Warehouse will find more specifics and an application form online.)

It’s highly unlikely that set decorators will purchase original work for movies or TV series (especially the latter) simply because of the expense of one-of-a-kind art. More common is buying the one-time rights to a piece, for a specific show and that show only. “I pay in the neighborhood of $250 per image,” says Cimino, “and ask for a release for that show only in perpetuity.” A digital file of the work can then be blown up or scaled down and transferred to the desired support (or made into a giclée print), with additional details (like impasto or facture) added to give it heightened authenticity.

And of course everything has to be cleared through the studio’s lawyers. “If you take a sculpture and hit someone over the head, it’s no longer a piece of art, it’s a weapon, and the artist might get ticked off,” says Fox, who cites a famous legal battle over art used in “The Devil’s Advocate,” a 1997 film starring Al Pacino as the head of a law firm who is literally Satan incarnate. In Hart v Warner Brothers, the claim was made that a sculpture in the apartment of the Pacino character closely resembled a sculpture by Frederick Hart on the façade of the Episcopal National Cathedral in Washington, DC, and that a scene involving the sculpture infringed on Hart’s rights under U.S. copyright law. After a sizable settlement was reached, Warner Brothers agreed to edit the scene for future release and to attach stickers to unedited videotapes to indicate there was no relation between the art in the film and Hart’s work. Given the expense and publicity attached to that case 20 years ago, artists (or their dealers) should not be surprised if they are required to sign off on paperwork that maappear initially daunting.

And how can you go about “auditioning” your work for inclusion in films and movies? As mentioned, the Artspace Warehouse is one way to go. Another is to seek out set decorators online. If there is a show you particularly admire, whose ambience might seem the perfect setting for your art, go to the International Movie Database (IMDb.com) and click on “cast and crew” in the upper right. The set decorator inevitably turns up, and these are for the most part not hard to track down. Some are on social media, like Facebook and LinkedIn, although a couple did not return my requests for an interview. Cimino adds that you can also reach out to the Set Decorators Society of America in Los Angeles.

And if all that seems like too much trouble, at least this post may have made you more alert to the art on the walls, bookshelves, and coffee tables of your preferred escapist entertainment. And with the Oscars so recently in the news, I think there should be a whole new category: Best Art at the Movies.

Ann Landi

Top: Bert Cooper’s office on “Mad Men.”

Some galleries work with film sets too and I’ve had designers come through open studios that have borrowed work. They pay a good rental fee, take good care of the work, and sometimes it sells on set ! And you get fun photos from the scenes!