Should You Have a Contract with Your Dealer?

Whether you have a piece of paper in hand or not, it's still a question of trust.Given the increasingly litigious nature of all aspects of our society, it comes as a surprise to find that many galleries and artists function happily without complicated contractual agreements. About half the people surveyed for this report—both artists and dealers—say they see no need for a lot of paperwork to bolster what should be a mutually supportive and nurturing bond that in some cases leads to close and lifelong friendships. In his 40 years as an art dealer, Hal Bromm says he has seldom had problems with the artists he represents. “If you have a good relationship and you’ve been working together successfully for a period of time, then you have the trust and faith that the relationship will continue.”

Clint Hulse and Jerry Warman installing a show of Ron Davis works at Hulse/Warman Gallery in Taos, New Mexico.

“Relationships evolve naturally,” adds Valerie McKenzie, who has had her own gallery for 13 years and is now on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. “The only disputes I’ve had are when an artist has done sales behind my back, and it usually signals the end of the relationship because that trust has been broken. But if you like each other and want to work together, you can usually work out the disagreements.”

But then there are the nightmare stories. On both sides. The dealers who disappear in the dead of night, who won’t pay for damaged art, who stick the artist with unexpected costs that weren’t spelled out upfront (such as an expensive magazine ad you’re pressured into buying or the show is off). And there are the artists who decide to litigate against those who represent them: claiming they never agreed to the standard 20 percent discount most galleries still mysteriously and inexplicably offer collectors, kvetching about not getting taken to art fairs or paid in full within 30 days. “Without a contract, an artist can sue you anywhere, depending on the laws of her home state, and different states have different laws,” says one dealer who asked for anonymity. After he was hounded by an unhappy painter who hadn’t made any sales in a couple of years, he ended up settling for half of what he described as an “outrageous amount” because it was preferable to spending time in court.

And yet the wrong contract can unnecessarily shackle artists who are ready to find a new and bigger audience and might benefit from greater exposure. Nance Frank, owner and director of Gallery on Greene in Key West, Florida, cites the case of a well-known New York gallery that “went to Cuba and signed a one-year exclusive contract with fifteen of the best artists. The director brought them to New York to have a show, and the show was crappy,” she says. “And now all those artists are tied up for a year.”

How you broach the subject of contracts with a gallery is easily as delicate an issue as bringing up the discussion of a pre-nup with someone you think you’d like to marry. The top-tier galleries like Gagosian and Pace (who will not talk to me–yet) most likely have battalions of lawyers and reams of paper to cover just about any contingency, but many of the best of the rest—galleries like Jack Shainman, Lesley Heller, Elizabeth Harris, Cheim & Read, and others—still do business on a handshake basis. Lesley Wayne, who shows with Shainman says, “I’ve never had a contract with Jack, and I’m also very organized. I know they keep records, but they don’t always turn those over to me. I’ve never had a painting lost and I know things can get damaged.” (And that’s where the gallery’s insurance kicks in.) When Wayne was just starting out, Shainman approached her and asked for exclusive representation. Her initial impulse was to say no, but “in the end I felt like if I wanted to keep my independence the responsibility would be on me to make things happen. And it didn’t seem a good groundwork to put up boundaries at the get-go.

Leslie Wayne with Untitled, (greenorangelavendar), 2012, oil on wood, at the Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, California.

“My advice to younger artists is to ask other artists who’ve had shows with any gallery that approaches you,” she continues. “Have a clear conversation with the dealer. What are you offering, what can I expect? Will you take the work to art fairs? They’ve become a mall mentality, but it’s one of the biggest ways to get the work out there.”

Beyond taking your work to a wider audience, there is much a good gallery can do to streamline your life. “When my artists are in group shows, the paperwork and everything else goes through my gallery,” says McKenzie. “What an artist gets from me is accurate on-time paperwork, PDFs of reviews, and other information so that the other gallery can put the work up on the wall and sell it.”

Upfront discussions about matters like percentages of sales to the gallery, studio sales, and advertising can help avoid conflicts down the road. The standard split is still 50-50, but that may vary according to medium. “Sculptors get a little more” at his gallery, says Jerry Warman of the Hulse/Warman Gallery in Taos, NM, because the materials are generally more expensive. Advertising will also vary from dealer to dealer. “If you make $500,000 for the gallery, you get $50,000 in advertising,” says Nance Frank. “But I also do public relations, chat up the press, and hire p.r. companies to work for my artists. And that’s worth ten times as much as an ad.” Dealers who believe advertising works say it’s not uncommon for an artist to share the costs. “But that should be in writing,” says Warman. Most dealers frown on studio sales—it’s the professional equivalent of extramarital cheating—unless some sort of arrangement is worked out in advance. And above all, dealers stress the importance of having documentation in the form of consignment sheets as to what work the artist has given to the gallery.

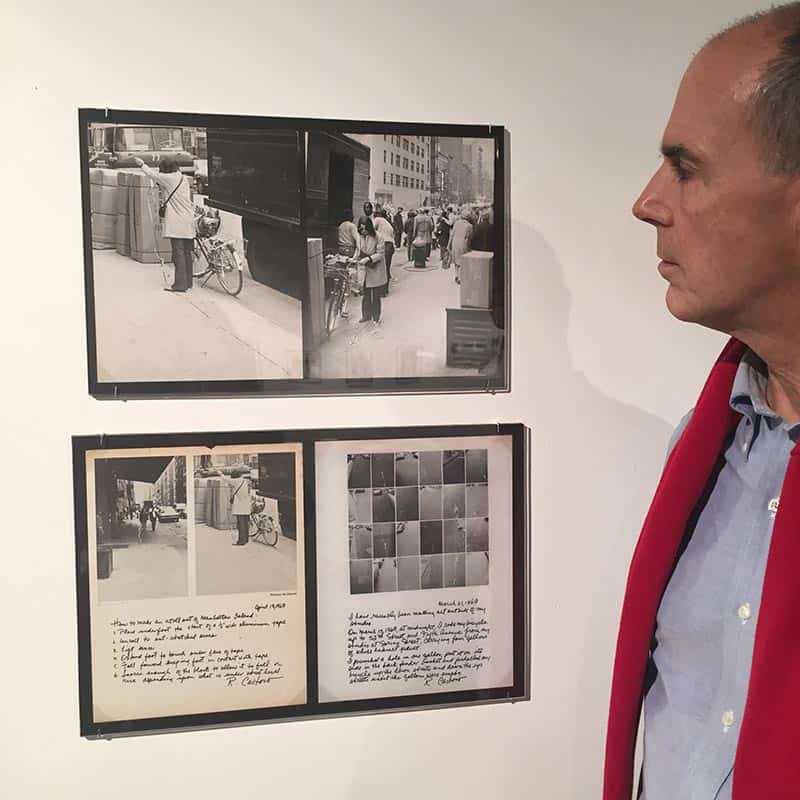

Dealer Hal Bromm with photos of the late Rosemarie Castoro’s 1969 “Street Works”: How to Make an Atoll Out of Manhattan and Leaking Paint

There are many many stories of artists getting screwed by dealers, but it’s nonetheless a street that runs both ways. The only time he’s had friction develop, says Bromm, “is when an artist says, It’s been great working with you but I’ve found another gallery that will do a better job. Well, if we’ve invested many years in your career, and if the relationship has been generally good, it’s only fair for the artist to give a small percentage of future sales or turn over works we can sell.”

In the end, of course, “a contract is only as good as the people who are making it,” says Warman. But if you, as an artist, feel more comfortable with that piece of paper in your files, below is an example of what it might look like. And here is an excellent guide to the legal niceties governing consignment agreements and artists’ reps: http://www.owe.com/resources/legalities/21-your-work-as-fine-art-part-2

Click Here to Download / View the Hulse/Warman Gallery Contract.

Article by Ann Landi

Photo credits: McKenzie Fine Art at 55 Orchard Street in New York. Photo of Leslie Wayne by Don Porcaro