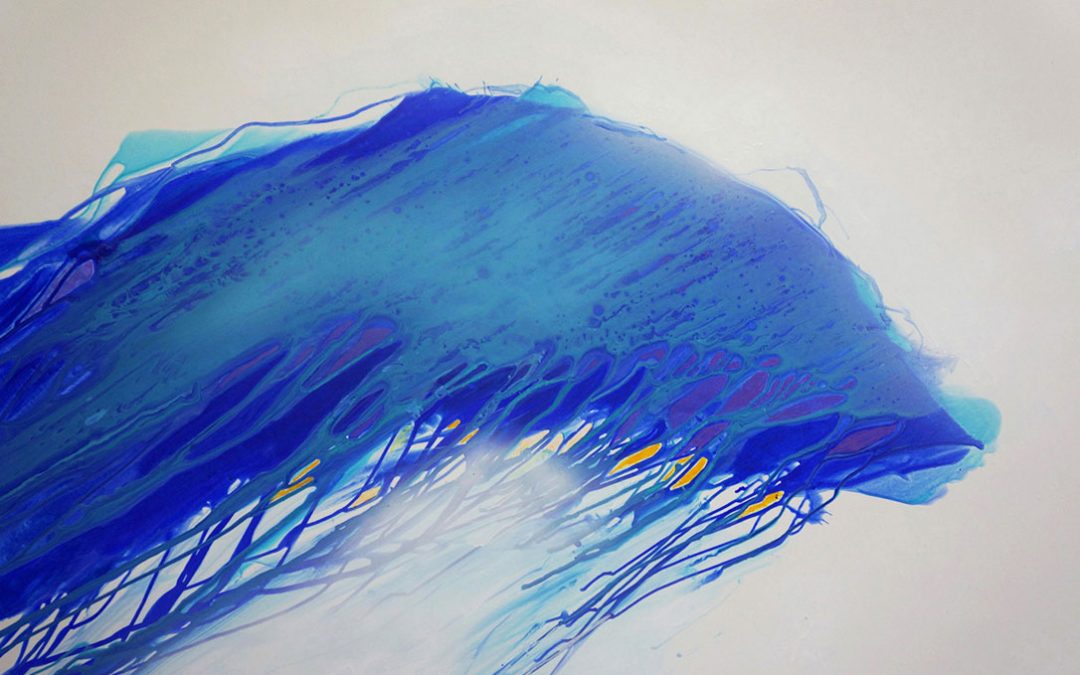

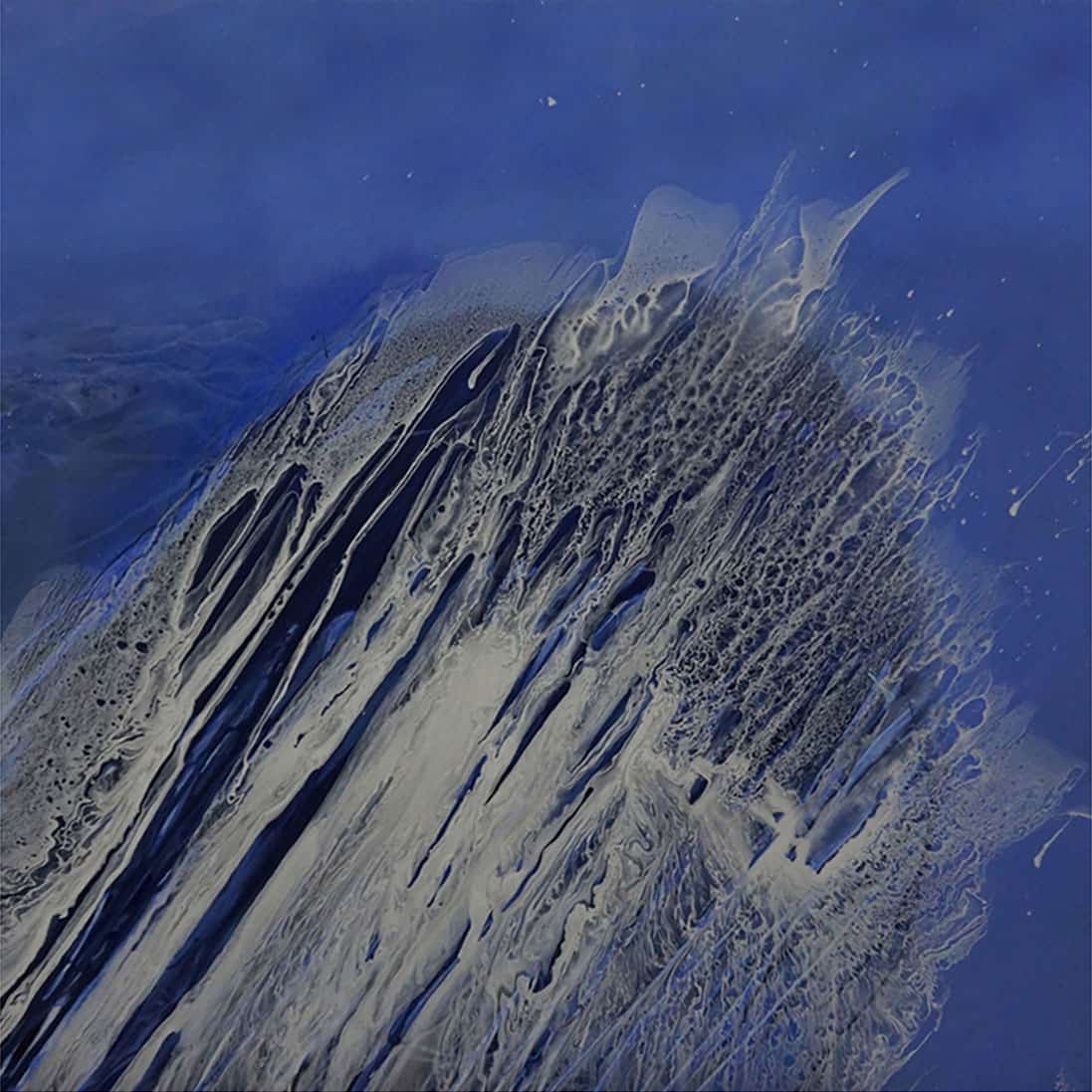

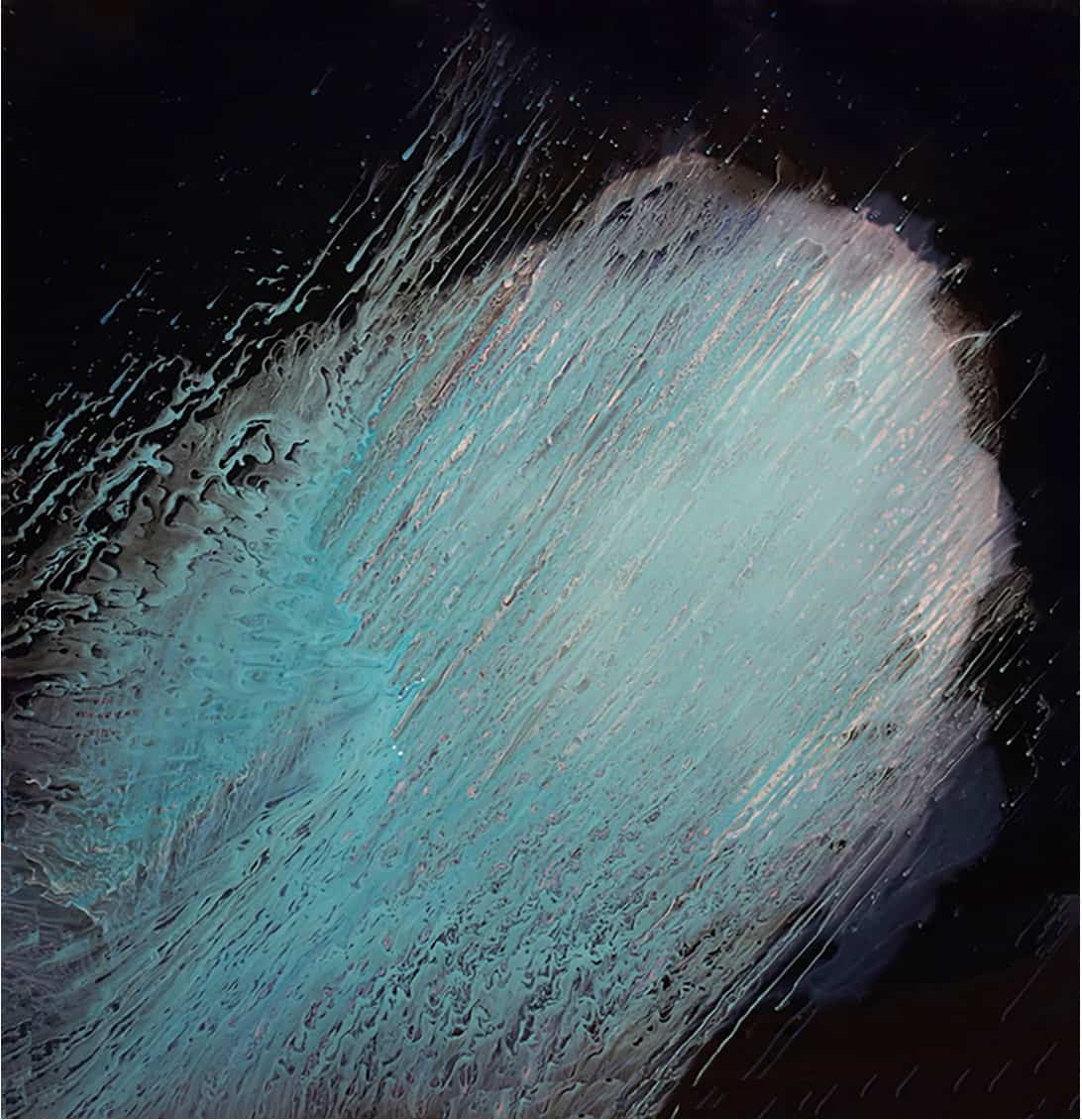

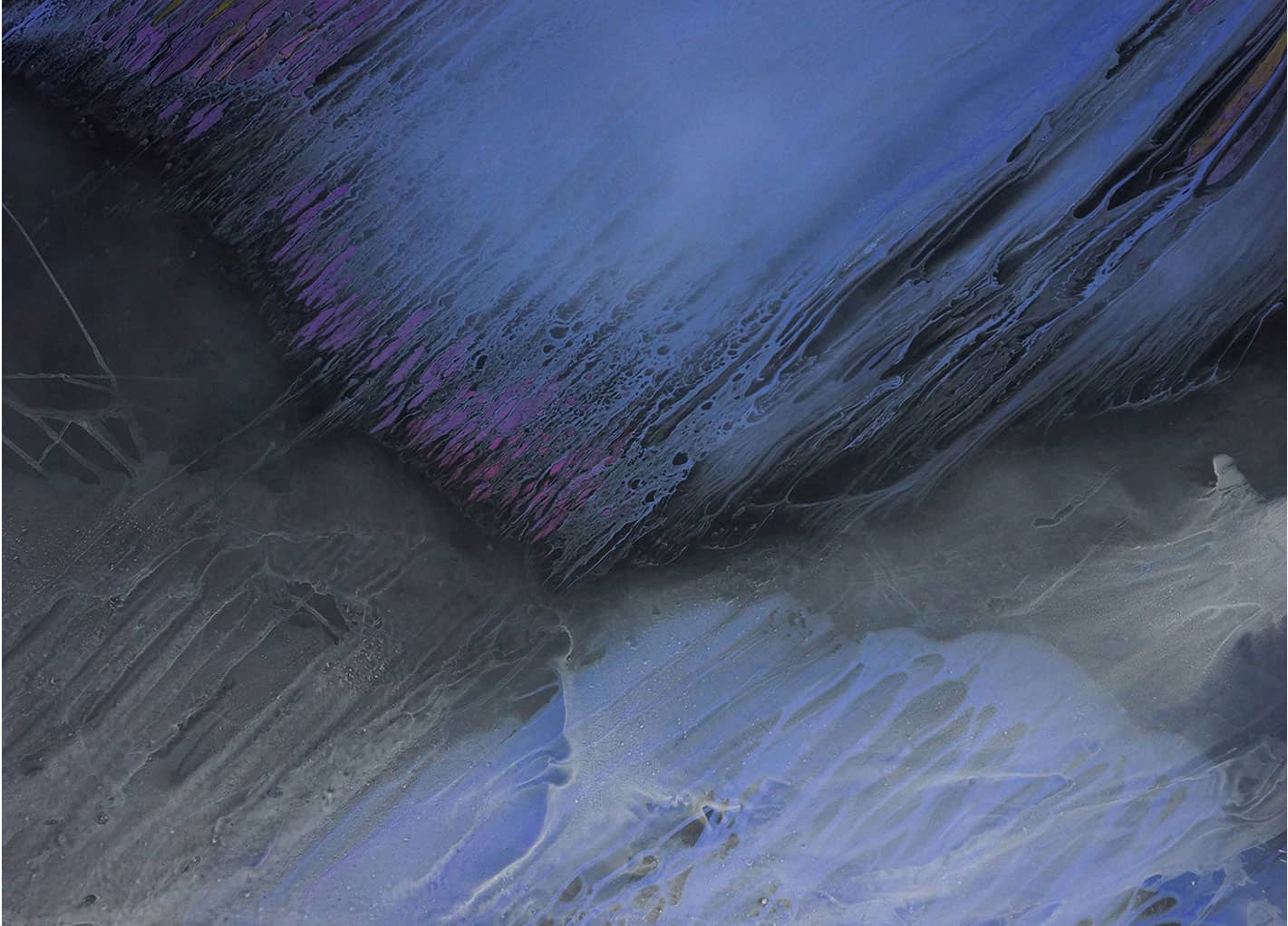

Sharon Weiner’s explosive paintings appear to have come into being through random acts of nature—tsunamis, tidal waves, maybe even collisions of meteors in deep space. In reality, the artist fabricates the works by building up several layers of poured acrylic paint and acrylic medium, sanding extensively between these until a “skin” appears on the surface. As she explains in her artist statement, “I apply the pigment and medium with brush and airbrush, rendering organic shapes across the canvas. I then pour more layers of medium over the shapes while refining and adding additional ones.”

Nevertheless, in spite of all those steps, the works convey a spontaneity that aligns her with an Abstract Expressionist tradition, and also with a history of searching for the transcendental in painting from established masters like Mark Rothko and Phillip Taaffe.

And yet little in Weiner’s upbringing pointed toward a career as an artist. “No one in my family had any interest in art except for a great aunt who was a painter, but more in a hobby kind of way,” she recalls. “I remember going to her house occasionally and seeing her still life paintings, and thinking it was the coolest thing that she was able to paint. She also had a library in her house and had fresh flowers delivered every week. It was so different from my life at home.”

Her parents—her dad was in the radiator business; her mother was a homemaker—discouraged any thoughts of a vocation in art. So she went off to the University of Missouri to pursue a degree in sociology. She met her future husband, Allen Weiner, who was then in medical school, while working at a hospital during a summer break from college. They were married by the time the artist was a senior and by the end of the school year she had a baby daughter.

The young family moved to Los Angeles, her husband’s hometown, in 1971. Weiner changed her mind about wanting to pursue social work and felt the urge to do something more creative with her life, and so enrolled in drawing and painting classes. After nearly two decades of making art, she decided to put together a portfolio and apply to Claremont University in Claremont, CA, for graduate work toward an MFA. There she recalls in particular the encouragement of Roland Reiss, recently described by a critic for the Los Angeles Times as “an artist interested in the sensuality of materials, the slipperiness of images and, above all else, the maximization of visual impact.”

Mark Rothko’s works also made a big impression on her, but curiously it was a trip to Italy in the early ‘90s and a visit to Padua to see Giotto’s fresco cycle in the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel that solidified her desire to pursue a career as a painter. “By the time we got to Padua, I was feeling slightly sick with a bad cold, exhausted, and burned out, and decided I didn’t want to get off the bus,” she remembers. “My husband encouraged me to check out the chapel. I was blown away—transported.” Though Giotto may seem an odd infatuation for an artist who eventually made her way into an entirely different vocabulary, one that draws on Modernist traditions, the trecento master’s powerful use of color and abstract shapes are in large measure what have made him an artist for the ages.

Weiner first began to work with the techniques that have led to her current practice around the turn of the millennium. “That eventually evolved into the kind of work I currently do—pouring and airbrushing—which allows me to have some control of the process but also opens up the possibilities of unexpected occurrences.

“While I’m very much influenced by the beauty and mystery of nature, my work also been about my interior world in dialogue with the outside world in a conscious and unconscious way,” she adds. With a psychiatrist husband and a daughter who is a psychologist, the artist has had a fair amount of exposure to the belief that dreams can be a way of understanding an inner life. She has also had personal experiences with “holistic psychoanalysis, which deals with the body, the mind, and the spiritual.

“This is all integral to my life and work.”

Ann Landi

Top: A Moment in Time (2017), acrylic on canvas, 42 by 60 inches

I have been captivated by all of Sharon’s work that I have seen via Vasari 21. I am fascinated by the trajectory from trecento to modernist legacies. I also love the dialogue between control and letting go into a materials nature/process, and the archetypal underlay – Brava Sharon and Ann