One of the most radical abstract artists of the last 50 years is scarcely a household name, or even well known outside a small group of collectors, connoisseurs, and art historians. But Mary Lee Bendolph is a standout in the group of quilters from Gee’s Bend, a tiny isolated community of mostly African-Americans tucked into a bend of the Alabama River, about 60 miles south of Selma. The strikingly original artists first came to national attention with a traveling exhibition, “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend,” that premiered in 2002 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and moved on to the Whitney Museum of American Art and the de Young Museum. The quilts by 45 quiltmakers earned rave reviews, including comparisons by the New York Times chief art critic Michael Kimmelman to Modernist masters like Paul Klee and Henri Matisse.

Now, through May 27, Bendolph is having a show of her own at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum in South Hadley, MA (to be followed by an adapted version at Swarthmore College in Swarthmore, PA, in the early fall). “We honed in on her because we have prints of hers in the collection,” says Hannah Blunt, associate curator at Mount Holyoke, “and because of her ability to pull together unexpected patterns and colors. ‘Fearless’ is one word that comes to mind.” The show, called “Piece Together,” features 18 quilts by Bendolph, as well as seven prints she created in collaboration with Paulson Bott Press (now Paulson Fontaine Press) in Berkeley, CA.

The seventh of 17 children, Mary Lee Bendolph was born in 1935 into conditions of poverty so extreme that in hard times Gee’s Benders survived by foraging for blackberries, squirrels, and turtles. As the catalogue for the show notes, “[T]hey also developed strong habits of gift-giving and reciprocity”—a community spirit exemplified in the Freedom Quilting Bee, a cooperative established in 1966 in which Bendolph briefly participated.

She made her first quilt, under her mother’s tutelage, at the age of 12. “It took her a very long time to make her first quilt because they had very little material,” recalled her son Rubin Bendolph Jr. in an interview in the show’s excellent catalogue. “Sometimes, she would find a piece of a rag on the side of the road. She would take it home and wash it and hang it out on the fence to dry, then rip it up and make a block in her quilt.”

That habit continued throughout her long life (Bendolph still lives in Gee’s Bend but has largely retired from quilt making since suffering a stroke in 2008). As her family grew in the 1950s and ‘60s, eventually comprising eight children in all, Bendolph used scraps from worn-out clothes. In a house heated only by a woodstove, the children would sleep with their siblings on a corn-shuck mattress cushioned by quilts, under several more quilts for warmth. These “provided a rare source of beauty while embodying communal labor and values,” notes Andrea Packard, the List Gallery director from Swarthmore College. “People would generally piece quilt tops during the winter months; each spring, they would hang their quilts on fences or clotheslines, comparing and admiring each others’ handiwork.”

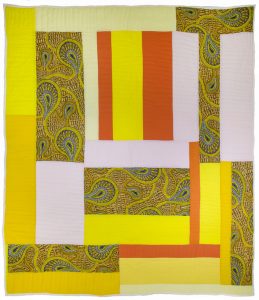

As striking as they are as highly original compositions of shape and color, Bendolph’s quilts carry a fair amount of family history, amounting almost to an encoded autobiography. “Old clothes have a spirit in them,” Bendolph has said. “They also have love. When I make a quilt, that’s what I want it to have too, the love and the spirit of the clothes and the people who wore it.” So in Husband Suit Clothes (Housetop Variation), one of three quilts she made shortly before the death of Rubin Bendolph Sr., she incorporated remnants of his dress clothes (“Loud, unmatching, stripes, color…that was my dad,” recalled his son and namesake.) Another quilt is composed entirely of scraps from dresses Bendolph had made for her only daughter, Essie Bendolph Pettway—a “practical way to hold on to a memory,” as Blunt notes in her essay. Another quilt, Dashiki, incorporates a shirt from Ruben Jr.’s high-school days, and summons up the dawn of the black pride movement, when these patterns became synonymous with declaring an allegiance to an African-American identity.

One of the most erratic and, yes, “fearless” of Bendolph’s quilts carries the reflection of a late-life determinedly buoyant state of mind. In Arrow, two central pieces form an upward-pointing triangle, set off by swatches in a brilliant rainbow of colors. Blunt reports the quiltmaker saying, “This arrow points in the direction I am now taking on life…upward, no more looking downward.” As the curator notes, “[T]he origins of Bendolph’s materials are not always what is most significant to her. She also prioritizes the idea, the design, and what it communicates about her experience.”

There are also abundant references in these brave abstractions to the world around her in Gee’s Bend. In the Architecture of the Quilt, a volume published by Tinwood Books in 2006, Bendolph reports: “Quilts is in everything. Sometimes I see a big truck passing by. I look at the truck and say, I could make a quilt look like that…I see the barn, and I get an idea to make a quilt. I can walk outside and look around in the yard and see ideas all round the front and back of my house….As soon as I leave the house I get ideas.”

Mary Lee Bendolph, with two of her children, Rubin Bendolph Jr. and Essie Bendolph Pettway, stand in front of quilts by Essie. Photo: Andrea Packard

There is perhaps no way to account for the particular genius of Mary Lee Bendolph, whose talents and vision were nurtured by so many different sources—including religion, family, and community. Unlike many contemporary artists, she certainly didn’t have the advantage of MFA programs or exposure to the whole pantheon of contemporary art (and perhaps the idea of the “artist” as we know it is alien to her vocabulary). But this stunning show and thoughtful catalogue expand the possibilities for sheer visual pleasure. Catch it while you can.

Ann Landi

“Piece Together: The Quilts of Mary Lee Bendolph” will be at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum through May 27, 2018, and at the List Gallery of Swarthmore College from September 6-October 28.

Top: Husband Suit Clothes (1990), mixed fabrics, 80 by 76 inches

All photos, but that of the Bendolph family, are by Laura Shea

Thanks for introducing me to this wonderful work and the story behind it!