Peter Roux believes an attraction to landscape, one of the principal motifs in his work, may stem from the many upheavals of his childhood. His father was a career marine and for the first 12 years of his life the family moved on average once a year. “I think I was struck early on by how different spaces looked in different parts of the country, and yet how similar they are,” he says. “When you’re a little kid, you have to find your own constants, you have to find similarities. But no matter where you live, you look up and you see clouds. That’s a language we all share.”

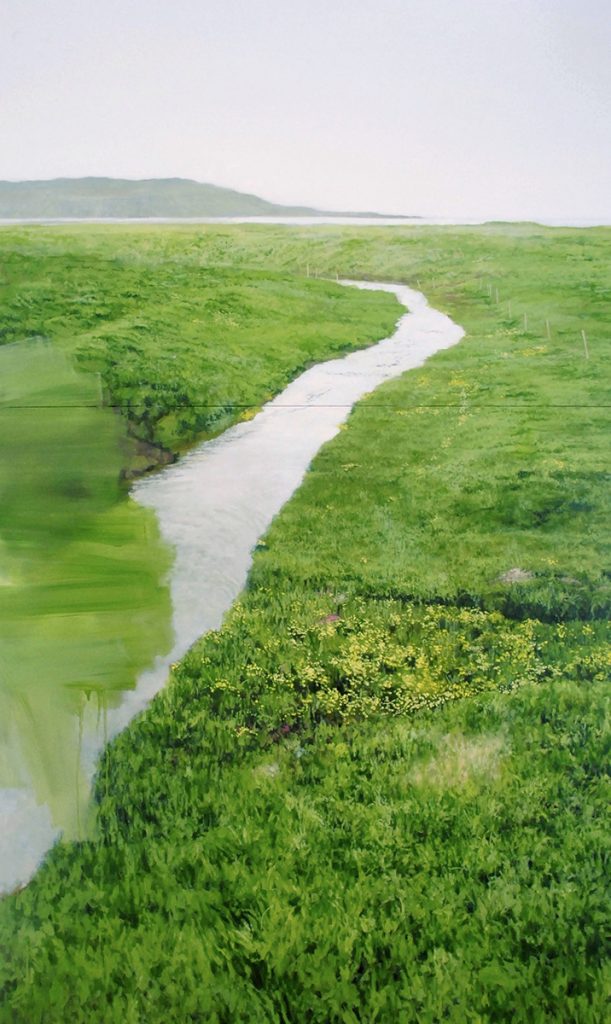

Roux settled into a less peripatetic life after his parents divorced and his mother relocated from rural Maine to Watertown, MA, just outside Boston. The move, he says, “opened up a world of culture for me,” and led to enrollment in the Massachusetts College of Art, where his ambition at first was to become an illustrator. But even at a young age his approach was so painterly that he was advised to look in other directions. “I was doing a lot of standard academic stuff as well as abstraction in college,” he recalls, “but I was always interested in landscape with an abstract bent.” It’s an impulse that has continued to this day, as the work oscillates between sumptuous visions of lush countryside, billowing hyperreal clouds, and complete abstraction realized in a minimalist palette.

After he graduated, Roux worked for a few years as a district manager for an operation much like Starbucks in the Boston area, and then when the real Starbucks moved in he found himself laid off but with a substantial amount of money put aside. He returned to Mass Art for an MFA when he was 25. “This was probably the point where I decided I’m not going off track again,” he says, “but I didn’t want to find myself just a full-time professor. My drive was different.”

Soon after graduation in 1997, Roux entered a competition to be included in New American Paintings, an annual publication that’s been around since 1993.

He was selected for the Northeast edition and given a three-page showcase for his work. “The week it came out I got about a dozen contacts from galleries,” he says, noting that this is not a guaranteed outcome for everyone selected. His work was more painterly and minimalist than it is now—“single trees, stark environments, not a lot of detail, with a quiet feel to it.”

Two years later he entered the competition again and had much the same results, with galleries as far away as Seattle and Atlanta reaching out to him. “This was all before the explosion of social media,” he notes. “The publication was one of the few platforms for emerging artists, and from those two catalogues I started building relationships.”

In the last few years, Roux’s practice has evolved to encompass three distinct bodies of work. The most epic is called the “Suspension” series, and features gorgeous explosions of clouds and sky juxtaposed with flat rectangles of color or slapdash scribbles and random marks that look to be lifted from another vocabulary entirely, though both are parts of the same visible reality. “When we see a cloud or a tree, we also see forms in space,” he explains. “We’re constantly shifting between finding things inside abstraction or abstracting shapes from things that are familiar.”

Another series, “The Mysteries,” was inspired by looking at the landscape from a moving car. “They are a bit of a bridge for me between representational and abstract,” he says. “I break the canvas into these not very complicated compositions of land and trees and sky.” Though most of his work starts with photos, these were not made from shots taken in a car. “The sense of motion started happening when I moved the paint around,” he says. “There is a temporal sense in those pieces, but I’m not interested in paintings that say, ‘This is what it looks like when you’re driving.’”

Roux’s third major body of work, “Dirty Angels,” is entirely abstract and started a couple of years after his mother died. The paintings are “more directly a reaction to an event than anything I’ve ever done,” he admits. “I’m not a religious person, but I was very close to my mother and when I lost her I started wondering if I would ever see her again. When I first started the series, I was responding to that feeling. I never believed in angels, but I love the idea that they might be out there.” The works are monochromatic, mostly black and white, and though they rely almost exclusively on line and rough scumblings of paint, they have an elegiac feel, somewhat like Cy Twombly’s series of canvases based on classical myths and allegories.

Noting that it’s not unusual for artists to develop more than one approach these days—Roux cites Bruce Nauman and Gerhard Richter as two who led the way—he says, “I’d rather find my voice by showing more range, even if that means I’ll probably make a lot more failures.”

About three years ago, for reasons both professional and personal, Roux moved from the Boston area to Asheville, NC, saying that he “had to leave some family to have another family.” He likes the area’s extraordinary physical beauty and his home’s proximity to downtown Asheville, a place he calls “super funky with a big liberal bubble.”

In his work as in his earlier life he describes himself as restless. “I have the opposite problem of artist’s block because I have so many things that I want to do that I have trouble keeping up with myself,” he says. “It’s a challenge for me to finish work because I can’t wait to get on to the next project.”

Ann Landi

Top: Suspension (take 6), 2017, oil and charcoal on canvas, 36 by 48 inches

Thank you for this lovely glimpse of Peter’s work. I enjoy seeing the three bodies of work that he is juggling and how they connect with one other visually.

Stunning work!

Top tier