Patricia Moss-Vreeland launched her career producing that most traditional of genres—still life. After pursuing studies at Washington University in St. Louis, MO, and the Philadelphia College of Art, she ended up in Rome as part of Tyler School of Art’s program abroad. “I had a short-lived infatuation with the landscape, and was smitten with the Futurists,” she recalls. She discovered a kinship with “the whole Italian thing”—the late Gothic and Renaissance architecture, the ochre and sienna palette of the city, the conversations with people who cared deeply about art.

When she returned to Philadelphia in the early 1970s, Moss-Vreeland developed a vocabulary for still life that merged the colors of the Renaissance with some of the elements of Futurist composition. She was enormously lucky (and sufficiently accomplished) to find a home with what is still one of the best galleries in the city: the venerable Locks Gallery, founded in 1968. “Marian Locks was my mentor,” she says. “I was very blessed to have her as a dealer because she was so giving, and I had an amazing career for 20 years.” During those two decades, Moss-Vreeland also turned to a kind of hyper-realistic portraiture, mostly in graphite on paper, works that demonstrate enormous skill along with a compassionate eye.

But by 1993, when she had her last show at Locks, she was ready to move on, noting, however, that “still life is still important to me, it’s part of who I am.” She and her husband, the sculptor and designer Robert Moss-Vreeland, applied for and landed the commission to design the “Memorial Room” for the Holocaust Museum in Houston, TX. The two envisioned “a place to address remembrance,” and the final space includes a wall of ceramic tiles, called the Wall of Tears, and hand-painted birch panels (by Patricia) comprising a Wall of Remembrance and a Wall of Hope. The memorial earned numerous awards and was described by the art critic of The Houston Chronicle, who compared the room with the Rothko Chapel, as a “space in which art serves as a conduit for private meditation.”

The project also opened up new territory for the artist. “I listened to memories from survivors and wondered, why did individuals remember and respond to the past and to life so differently?” she told an interviewer for Interalia Magazine in 2016. “Each survivor contained a mountain of grief—some of them escalated to new heights, and others failed to make the climb.”

Since that time, Moss-Vreeland’s studio practice has concentrated on the mysteries of memory. Soon after completion of the Holocaust memorial room, she won another commission, this time from the University City Science Center in Philadelphia to design a multidisciplinary exhibition that explores the art and science of memory and its relationship to learning and creativity. For this ambitious exploration, she enlisted the help of Dr. Barbara Malamut, the head of neuropsychology at Jefferson University Hospital. The collaboration showed her that memory is a subjective process, placing it firmly in the realm of art as well as science. “I learned that our memories are not fixed; each memory is a constantly shifting reconstruction of experience and emotion,” she explained to Interalia. “How you feel when something occurs will become the context for how you remember that event.”

The exhibition “Memory Connections Matter” integrated her research along with new images and poetry to create what one reviewer called “a metaphoric walk through the brain.” Visitors could learn about art and science in contemporary culture, while contributing their own memories as part of the show’s interactive components. In 2004, the show traveled to the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, MN, and eventually led to conferences, residencies, and a TEDx talk, all of which opened up new possibilities for considering memory, creativity, and art.

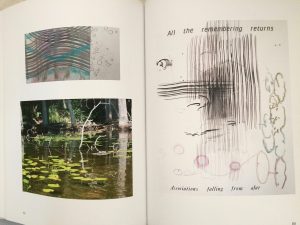

In 2011, Moss-Vreeland published a book called A Place for Memory, a compilation of her observations, poems, prints, drawings, and photography that sums up eight years of research into the study of how we remember. “The book was an extension of the installation,” she says, “a way of teaching about the use of metaphor and braiding ideas together.”

These days the artist is at work on another book. “The first one left out the Holocaust research, and this one will be much more about the emotions that memory provokes. I felt that part of the story wasn’t told, that there are emotional connections we sometimes don’t recognize.”

Since 1998, Moss-Vreeland has also been designing and leading interactive workshops dealing with memory and its relationship to creativity, the senses, and social issues. “These are designed to be informal and engaging,” she says on her website. “Each participant creates something that has personal meaning, and provides new ways of recollecting, seeing and finding patterns of connections. When we examine memory, there’s the potential to understand our own individual experience more fully, to see who we are—and at the same time find points of connections with others.”

In all her endeavors, the artist says, “I think of myself as being a citizen. I’m finding it fun to have this activist part of myself, inviting people to cross over from other disciplines. The more I delve into the connections with memory, the more I see that artists are messengers for what goes on in the world.”

Top: An installation shot from “Memory Connections Matter” (1999-2000)

Great article. Would love to connect and talk more about memory.

Thanks for the story. I know Patricia but did not know her background. Great work!

Well done!